Wishing a merry Christmas to all my readers who celebrate the holiday!

Here, from a past post, are two images of the Nativity from southwest German eighteenth-century bibles. (Full story.)

"In fiction, the principles are given, to find

the facts: in history, the facts are given,

to find the principles; and the writer

who does not explain the phenomena

as well as state them performs

only one half of his office."

Thomas Babington Macaulay,

"History," Edinburgh Review, 1828

Showing posts with label Book History. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Book History. Show all posts

Sunday, December 25, 2016

Friday, December 2, 2016

Civic Forum: The Velvet Revolution of November 1989 and Beyond

Because I'm teaching my course on modern East Central Europe again this fall, it seems an appropriate time to remember the so-called "Velvet Revolution" (a sappy term I never liked) in the course of which dissidents peacefully forced the hard-line Czechoslovak communist regime from power in 1989.

The driving force behind the revolution were the dissidents such as Václav Havel, associated with the Charter 77 human rights movement. As the spirit of protest spread throughout the bloc in the fall of 1989, they organized themselves as the "Civic Forum" (Občanské fórum, OF).

I acquired this small--I guess you would call it a (?)--mini-placard some years ago in a Prague antiquariat. It displays the name of the organization against the background of the Czechoslovak flag. It is the size of a small bumper sticker (193 x 63 mm.) but is printed on stiff (now yellowed) pasteboard and thus lacks adhesive, which makes me wonder what its intended use was: for display in apartment or store windows? (After all, Havel's famous essay on "the power of the powerless" anchors its notion of "living in truth" in the story of those who agree vs. decline to accede to the regime's supposedly meaningless and harmless demand that they place its propaganda signs in their windows.) For display in an automobile? And when? The dampstaining at the bottom suggests that it was actually placed in a window where it would have been subject to condensation arising from a heated interior in cold weather.

It is at once an inspiring and a sad memento. Although Czechoslovakia had been an island of liberal democracy among the post-World War I successor states that drifted toward authoritarianism, it became one of the most hardline communist states after 1948, and indeed, its leaders (in contrast to those of Hungary and Poland) refused even to nod to the de-Staliniziation "thaw" in the wake of Krushchev's denunciation of Stalin's crimes in 1956. Following the short-lived and optimistic episode of the "Prague Spring," crushed by Warsaw Pact tanks in August 1968, the regime pursued a quietly brutal policy of "normalization."

Despite this long history of resistance to reform, the communist regime collapsed in only ten days in 1989 in the face of determined citizens jingling their keys and refusing any longer to be afraid. Former dissident Václav Havel became president at the end of December 1989.

By 1991, however, the movement split into conservative-capitalist and liberal factions. The latter triumphed in the elections of 1992, and the latter passed from the scene. A cautionary tale about politics in more ways than one.

The driving force behind the revolution were the dissidents such as Václav Havel, associated with the Charter 77 human rights movement. As the spirit of protest spread throughout the bloc in the fall of 1989, they organized themselves as the "Civic Forum" (Občanské fórum, OF).

I acquired this small--I guess you would call it a (?)--mini-placard some years ago in a Prague antiquariat. It displays the name of the organization against the background of the Czechoslovak flag. It is the size of a small bumper sticker (193 x 63 mm.) but is printed on stiff (now yellowed) pasteboard and thus lacks adhesive, which makes me wonder what its intended use was: for display in apartment or store windows? (After all, Havel's famous essay on "the power of the powerless" anchors its notion of "living in truth" in the story of those who agree vs. decline to accede to the regime's supposedly meaningless and harmless demand that they place its propaganda signs in their windows.) For display in an automobile? And when? The dampstaining at the bottom suggests that it was actually placed in a window where it would have been subject to condensation arising from a heated interior in cold weather.

It is at once an inspiring and a sad memento. Although Czechoslovakia had been an island of liberal democracy among the post-World War I successor states that drifted toward authoritarianism, it became one of the most hardline communist states after 1948, and indeed, its leaders (in contrast to those of Hungary and Poland) refused even to nod to the de-Staliniziation "thaw" in the wake of Krushchev's denunciation of Stalin's crimes in 1956. Following the short-lived and optimistic episode of the "Prague Spring," crushed by Warsaw Pact tanks in August 1968, the regime pursued a quietly brutal policy of "normalization."

Despite this long history of resistance to reform, the communist regime collapsed in only ten days in 1989 in the face of determined citizens jingling their keys and refusing any longer to be afraid. Former dissident Václav Havel became president at the end of December 1989.

By 1991, however, the movement split into conservative-capitalist and liberal factions. The latter triumphed in the elections of 1992, and the latter passed from the scene. A cautionary tale about politics in more ways than one.

Saturday, November 26, 2016

Post-Thanksgiving Book History Post

What to do on that long Thanksgiving weekend after you've eaten your fill and watched too much TV? Turn to your books (or collections).

In this case, it's the ex libris, or bookplate: an interesting testimonial to evolving habits of book ownership, and since the late nineteenth century, a profitable and collectible small graphic genre (1, 2) in its own right.

This one was created by the Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants (not my ancestors, God knows--though I do know more than one student who can claim membership in that elite club). Founded in 1896, the organization soon decided that it needed an ex libris to accompany donations it made.

An "American Letter" by Charles Dexter Allen of Hartford (Nov. 9, 1897) in the British Journal of the Ex Libris Society announced a competition:

Below is Heil's winning design, from my small collection. The reddish ink has a metallic cast, which, viewed from some angles, causes it to reflect light. The back is gummed.

Reviewing a bookplate exhibition by the Boston Arts and Crafts Society at Copley Hall in 1899, the journal of the Berlin Ex-libris association called this piece "a very beautiful plate!"

I might quibble with that. Even aside from the generally retrograde aesthetic (the minimal nod to modish art nouveau taste in the left marginal column notwithstanding) and corresponding social-political doctrines, the highlighting of the key initial letters on the left is bizarrely violated by the awkward breaking of the word, "Descendants." It is jarring, conflicts with the supreme principle of legibility.

Still, I am very glad to have this historically significant piece in my collection. I don't have a copy of the second-place design, but one day ... who knows?

In this case, it's the ex libris, or bookplate: an interesting testimonial to evolving habits of book ownership, and since the late nineteenth century, a profitable and collectible small graphic genre (1, 2) in its own right.

This one was created by the Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants (not my ancestors, God knows--though I do know more than one student who can claim membership in that elite club). Founded in 1896, the organization soon decided that it needed an ex libris to accompany donations it made.

An "American Letter" by Charles Dexter Allen of Hartford (Nov. 9, 1897) in the British Journal of the Ex Libris Society announced a competition:

The Society of Mayflower Descendants offers two prizes, one of fifty dollars and the other of twenty dollars, for a book-plate design. The plate is to be 4 1/2 by 3 inches, and the design in the centre should be 2 1/4 by 1 3/8 inches. Above this should be the title, "Society of Mayflower Descendants in Massachusetts," and at the bottom, "Presented by," with space for date and name of donor. The office of the Society is in the Tremont Building, Boston.

The following year, Allen reported on the winners. He began with an apology for his long silence:--Vol. 7 (1897): 178-79, quotation from 178

So many months have gone by without a communication from the American correspondent, that I feel assured these present lines will be read as a decided novelty, and I am not certain that an introduction is not in order ! But really during the hot and hottest months there seemed little doing in matters of interest to book-plate collectors, though, in fact, discoveries were being made, new plates were being designed and engraved, and the ongo of matters was not wholly interrupted. But with the return of weather that makes one think of the fireside and indoor delights, correspondence is resumed and matters of general interest are passed about from one to another.He reported on the creation of the smallest bookplate in the world (for a miniature book), and then, not bothering with a transition, launched into an update on the Mayflower contest:

Within a few months a competition for a bookplate was advertised by the Society of Mayflower Descendants in Massachusetts, and at a meeting held last March the first prize, fifty dollars, was awarded to Mr. Charles E. Heil, of Jamaica Plain, and the second, twenty dollars, to Mr. Theodore Brown Hapgood, jun., of Boston. At this meeting the sixty-eight designs submitted in competition were exhibited. The successful design has been printed in black with red capitals, and makes a very showy appearance. The lettering is good, and the pictorial design represents two Puritans, one in the layman's dress and one in the soldier's, standing by the sea-shore. At a little distance rides the Mayflower. Mr. Hapgood's design, printed wholly in black, represents the Puritan and his wife en route to church along the bleak shore, gun on shoulder, and clad in the sombre habiliments of the day. The old-style lettering and ornamentation are very pleasing, and one is impressed with the spirit of the design, which is in complete harmony with the picture and with the traditions the Mayflower Society endeavours to keep alive.Heil (1870-1950), a member of the newly founded Boston Society of Arts and Crafts (1897; today, the oldest such organization in the nation) came to be best known for his ornithological painting and has been called a second Audubon. Hapgood (1871-1938), by contrast, devoted more time to the world of book art, from binding design, title pages, and illustrations, to the ex libris (along the way finding time for ecclesiastical vestments and other artistic pursuits).

--Journal of the Ex Libris Society, 8 (1898): 171-72; here 172

Below is Heil's winning design, from my small collection. The reddish ink has a metallic cast, which, viewed from some angles, causes it to reflect light. The back is gummed.

I might quibble with that. Even aside from the generally retrograde aesthetic (the minimal nod to modish art nouveau taste in the left marginal column notwithstanding) and corresponding social-political doctrines, the highlighting of the key initial letters on the left is bizarrely violated by the awkward breaking of the word, "Descendants." It is jarring, conflicts with the supreme principle of legibility.

Still, I am very glad to have this historically significant piece in my collection. I don't have a copy of the second-place design, but one day ... who knows?

Sunday, November 20, 2016

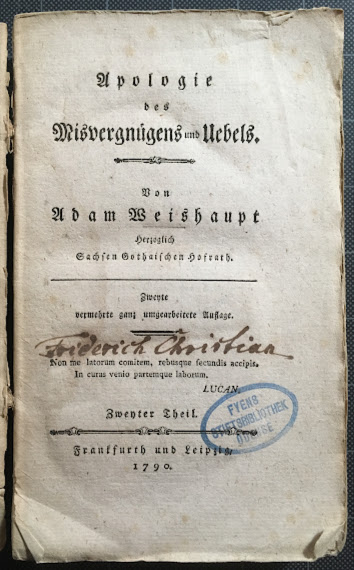

18 November 1830: Death of Adam Weishaupt, founder of the Illuminati

On 18 November 1830, Adam Weishaupt (b. 1748), founder of the Illuminati, died, age 82. Rarely does the modest achievement of a man stand in such disproportion to his historical reputation: the Illuminati stand at the center of one of the world's most enduring conspiracy theories, stretching from the debates over the French Revolution to today's popular culture. (Look it up yourself: it will be a good exercise in information literacy, i.e. separating real historical knowledge from bullshit.)

What I am sharing here is the title page of a little treasure from my personal library: the second edition of the second volume of Weishaupt's Apology of Discontent and Dissatisfaction (1790) a rather tedious (by modern standards; the readers of the eighteenth century were made of hardier stuff) dialogue about religion, philosophy, social change, and the meaning of life: at 366 pages. The book is unbound and remains in its worn blue interim paper wrapper, as issued.

What makes it special to me is actually less the authorship (though that is important) than the ownership: the title page bears the signature of the Friedrich Christian, Hereditary Prince of Augustenborg, in Denmark. In 1791, he granted the great German poet Friedrich Schiller a three-year pension to support him during a period of ill health. Schiller expressed his gratitude by setting forth his evolving ideas about aesthetics in a series of letters to the Prince, which formed the basis for his influential philosophical treatise, On the Aesthetic Education of Mankind (periodical publication, 1795; book edition, 1801).

Friedrich Christian reigned as Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg from 1794 until his death in 1814. The stamp of the famous Fyens (=Funen) Diocesan Library of Odense appears on the title page and inside cover, and a manuscript note on the latter indicates the book passed to that institution in 1816.

Created in 1813, the library reflected the theological needs of the clergy but was dedicated to "maintaining the scientific spirit and increasing the sum of knowledge for anybody in the province who loves science." By the 1830s, the Citizen's Library operated out of the same building. In the course of the twentieth century, the collection was merged first with that of the Odense Central Library and then the Library of the University of Southern Denmark.

The theological volumes (3,000 out of the total collection of 30,000) passed to the Library of Fuller Theological Seminary in 1948. (This volume appears in the 1902 catalogue under the category of Christian Morality, subheading Mixed Moral Writings.)

What I am sharing here is the title page of a little treasure from my personal library: the second edition of the second volume of Weishaupt's Apology of Discontent and Dissatisfaction (1790) a rather tedious (by modern standards; the readers of the eighteenth century were made of hardier stuff) dialogue about religion, philosophy, social change, and the meaning of life: at 366 pages. The book is unbound and remains in its worn blue interim paper wrapper, as issued.

Friedrich Christian reigned as Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg from 1794 until his death in 1814. The stamp of the famous Fyens (=Funen) Diocesan Library of Odense appears on the title page and inside cover, and a manuscript note on the latter indicates the book passed to that institution in 1816.

Created in 1813, the library reflected the theological needs of the clergy but was dedicated to "maintaining the scientific spirit and increasing the sum of knowledge for anybody in the province who loves science." By the 1830s, the Citizen's Library operated out of the same building. In the course of the twentieth century, the collection was merged first with that of the Odense Central Library and then the Library of the University of Southern Denmark.

The theological volumes (3,000 out of the total collection of 30,000) passed to the Library of Fuller Theological Seminary in 1948. (This volume appears in the 1902 catalogue under the category of Christian Morality, subheading Mixed Moral Writings.)

* * *

Sunday, October 16, 2016

Happy Dictionary Day, 2016

"Dictionary Day" honors lexicographer Noah Webster, born October 16, 1758, and celebrated for his pioneering work in both documenting and defining the emergent American language.

Webster is most often associated with Connecticut--New Haven, because he studied at Yale and spent his later years in that city (though his 1823 house was moved to Henry Ford's Greenfield Village in Michigan, in order to prevent its impending demolition)--and West Hartford, where his birthplace is today a museum and educational center dedicated to his legacy. In addition, however, he spent a crucial phase of his life (1812-22) in Amherst where he was actively involved in civic affairs (including the founding of Amherst Academy and Amherst College) as well as work on his dictionary.

Webster owned a large farm in what is now the center of town.

From the vaults:

• 2008: New England Celebrates Noah Webster 250th

• 2010: Well, where are you? Celebrating Noah Webster's Birthday and Searching for Remains of His Property

Webster owned a large farm in what is now the center of town.

|

| 1920s map of Webster's holdings (Jones Library Special Collections) [placeholder] |

His house no longer survives, but was located where the late

nineteenth-century "Lincoln Block" now stands, across from Town Hall.

From the vaults:

• 2008: New England Celebrates Noah Webster 250th

• 2010: Well, where are you? Celebrating Noah Webster's Birthday and Searching for Remains of His Property

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

30-31 May 1942: First Thousand-Bomber Raid on Germany (and an early infographic)

Serendipity is a pleasing thing. Several days ago, one of my tweeps*, looking ahead to this year's anniversary of the first thousand-bomber raid in world history, drew my attention to a New York Times Op-Ed piece marking the fiftieth. As it happened, I had for other reasons been sorting through my old World War II periodicals and came upon coverage of the event in the Illustrated London News (ILN; a popular periodical that celebrated its centennial in 1942 and managed to cling to life till 2003). A few days later, a modern poster in turn raised a connection to the ILN story. So it goes.

"1,046 Bombers but Cologne Lived"?

The contrast in the coverage is instructive. There is nothing objectively incorrect about the Times piece by Max G. Tretheway, a World War II Australian flight instructor, who notes that some of his students took part in the raid. Still, there is nothing new, either, and the message is both intellectually and morally banal. Its perspective is the typical modern one of presumably sophisticated irony, as can be seen from the title: "1,046 Bombers but Cologne Lived." The irony derives from the gap between expectations and consequences. Like many modern commentators, Tretheway points to the exaggerated hopes of air force men in the ability of strategic bombing to determine the outcomes of wars. It might be news to the average reader of the Times--but not historians.

Even though the raid and resultant 5,000 fires destroyed "90 percent of the central city" (he tells us) killing 474 (actually a stunningly low figure, given the primitive technology of the day and compared with later missions), wounding 5,000, and leaving 45,000 people homeless:

But how did the British press see the event at the time? The Illustrated London News coverage--addressed to a British population suffering under the onslaught of Nazi bombers--sought to provide readers with hope: "Here was terrible proof of the growing power of the Royal Air Force. 'This proof,' in the words of the Prime Minister, 'is also herald of what Germany will receive, city by city, from now on.'"

The profile of Air Marshal Arthur "Bomber" Harris contains the sorts of unfortunate hyperbolic claims that Tretheway and historians nowadays like to mock:

At the time, of course, no one really knew. It had never been tried. Advocates believed in their ability to deliver devastating blows from the air in part because they feared the enemy's capacity to do so. The bombing campaigns were terrible, but the cost was infinitesimal in comparison with what had been anticipated. The British expected that the German assault from the air would cause 2 million casualties in two months. In fact, the death toll from German air raids during the entire war was only 60,000.

And whereas Tretheway presents the survival of the Cologne Cathedral--an

icon of German national identity--as some sort of miraculous survival

or even rebuke to the raiders, the ILN correctly explains that it "was deliberately left unscathed by our armada in the great raid."

Twisting the knife a wee bit, the magazine notes that the cathedral, at least in its present form, is not so old anyway, having been completed only in the late nineteenth century.

Just to make things clear, the magazine contrasts the scrupulous policy of RAF toward cultural heritage with that of the Luftwaffe and its so-called "Baedeker Raids" (1, 2, 3; the name derives from the popular German tourist guidebooks of the day) deliberately targeting cultural heritage--including many cathedrals older than that of Cologne.

Indeed, it presents the German bombing of historic Canterbury as deliberate and unjustified vengeance for the Cologne raid.

Aviation infographics then and now

Oh--and that infographic?

When visiting friends for a party on this Memorial Day, I saw hanging on the wall a striking poster depicting US naval aviation resources, the work of a French geographer.

It reminded me of what I had seen in the ILN the day before. In order to give the public an impression of the size and power of a 1,000-bomber raid, the publication produced this forerunner of the infographic.

Not bad. Not bad at all.

• h.t. @B36Peacemaker for prompting me to write about this in the first place

• and follow @airminded who knows more about all this than I ever will (I assume he will correct me if I have made any gross errors here)

"1,046 Bombers but Cologne Lived"?

The contrast in the coverage is instructive. There is nothing objectively incorrect about the Times piece by Max G. Tretheway, a World War II Australian flight instructor, who notes that some of his students took part in the raid. Still, there is nothing new, either, and the message is both intellectually and morally banal. Its perspective is the typical modern one of presumably sophisticated irony, as can be seen from the title: "1,046 Bombers but Cologne Lived." The irony derives from the gap between expectations and consequences. Like many modern commentators, Tretheway points to the exaggerated hopes of air force men in the ability of strategic bombing to determine the outcomes of wars. It might be news to the average reader of the Times--but not historians.

Even though the raid and resultant 5,000 fires destroyed "90 percent of the central city" (he tells us) killing 474 (actually a stunningly low figure, given the primitive technology of the day and compared with later missions), wounding 5,000, and leaving 45,000 people homeless:

He goes on to cite more statistics, leading to his inevitable conclusion:When survivors of the world's first 1,000-bomber raid ventured warily out of their shelters, there before their unbelieving eyes, towering majestically above the hellish carnage stood their beloved cathedral - superficially damaged, but with its twin spires still silhouetted defiantly against the bomber's moon.This miraculous sight strengthened the people's morale and determination through the rest of the war, as the Allies continued to pound an already flattened city long after any real targets remained.

The Allies released an incredible total of 1,996,036 metric tons of bombs on Germany and German-occupied Europe, more than half of which fell on cities and communication facilities. Some 593,000 civilians were killed, and 3.3 million dwellings were destroyed, leaving 7.5 million people homeless.Nothing that would have surprised Churchill, Roosevelt, or Stalin. (They did not improvise D-Day or "the Battle for Berlin" at the last minute because the air campaign did not work out). Amidst all the talk of much more sophisticated "smart bombs" and "shock and awe" during the two US wars with Iraq, we also saw other commentators remind us that the war is not really over until the victor has boots on the ground (to use that hackneyed phrase) and enjoys a drink in the officer club of his foe. What the extreme critics of air power neglect to acknowledge is its success. To say the Allied air campaigns did less than had been hoped to damage either production or morale is not to say that they were completely ineffectual: they also forced the diversion of vital resources from the front, and in the latter phases of the war, the Allies enjoyed complete superiority in the air, which greatly aided the campaign on the ground. And, although most Germans refused to be bombed into despair or revolt against the regime, a surprising number began to regard the Allied air campaign as the punishment by Providence for their crimes, including the Holocaust: a self-pitying attitude motivated by fear rather than guilt, to be sure, but remarkable nonetheless.

The most frequently bombed city was Berlin; many other urban areas were close behind.

And yet it was necessary for the Allies to invade the Continent, and to fight to the very gates of the capital before Germany finally capitulated in May 1945, three years after the first saturation bombing of Cologne.

But how did the British press see the event at the time? The Illustrated London News coverage--addressed to a British population suffering under the onslaught of Nazi bombers--sought to provide readers with hope: "Here was terrible proof of the growing power of the Royal Air Force. 'This proof,' in the words of the Prime Minister, 'is also herald of what Germany will receive, city by city, from now on.'"

were it possible to put 1000 bombers over Germany night after night, the war would be over by autumn. It is another of his beliefs that were it possible to send over 20,000 'planes to-day the war would be over tomorrow.

At the time, of course, no one really knew. It had never been tried. Advocates believed in their ability to deliver devastating blows from the air in part because they feared the enemy's capacity to do so. The bombing campaigns were terrible, but the cost was infinitesimal in comparison with what had been anticipated. The British expected that the German assault from the air would cause 2 million casualties in two months. In fact, the death toll from German air raids during the entire war was only 60,000.

|

| the cathedral, virtually unscathed amidst the ruins (from the RAF report on the raid) |

Twisting the knife a wee bit, the magazine notes that the cathedral, at least in its present form, is not so old anyway, having been completed only in the late nineteenth century.

Just to make things clear, the magazine contrasts the scrupulous policy of RAF toward cultural heritage with that of the Luftwaffe and its so-called "Baedeker Raids" (1, 2, 3; the name derives from the popular German tourist guidebooks of the day) deliberately targeting cultural heritage--including many cathedrals older than that of Cologne.

Indeed, it presents the German bombing of historic Canterbury as deliberate and unjustified vengeance for the Cologne raid.

Oh--and that infographic?

When visiting friends for a party on this Memorial Day, I saw hanging on the wall a striking poster depicting US naval aviation resources, the work of a French geographer.

|

| [enlarge] |

|

| [actual figures from RAF] |

Not bad. Not bad at all.

* * *

• h.t. @B36Peacemaker for prompting me to write about this in the first place

• and follow @airminded who knows more about all this than I ever will (I assume he will correct me if I have made any gross errors here)

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Town Meeting: purest participatory democracy--or "mental torture, in which the victim actively collaborates"?

"Town Meeting was absolutely awful last night."

"How bad was it?

"It was SO bad that...."

It reads like a corny joke, but it was in fact a conversation I had many times last week, and there was nothing funny about it.

Like many other Amherst and New England residents, I've occasionally poked good-natured fun at this venerable democratic institution because it is so much a part of our culture and identity: it reveals our essential nature, brings out the best, the worst, and the silliest in us.

The issue has become more acute, though, since voters this spring approved a Charter Commission to review the form of Town government, a process that could result in any of several recommendations, including abolition of Town Meeting. Some would relish that outcome, others would fight it to the death. Part of the decision may turn on how effective Town Meeting proves to be under the magnifying class of increased scrutiny in the coming year. The omens are not good. In the past, I thought, the prospect of a Charter vote forced residents to be on their best behavior. Not this time. If anything, the atmosphere is more charged than ever.

The previous Town Meeting sessions this spring already displayed a few foibles and failures (1, 2, 3), but May 16 far surpassed anything we had seen. For a variety of reasons, the debate degenerated into unadulterated nastiness.

The no-go zone

The warrant article itself was simple and straightforward: The Jones Library, using money voted by a previous Town Meeting, is preparing a proposal for a building expansion in a highly competitive state grant program. It requested that the Amherst Historical Society (on whose board I serve), located next door in the Amherst History Museum, sell it a small piece of property that would facilitate this expansion. However, because a change in the dimensions of the Museum property, still zoned residential (a historical anachronism), would bring the remaining lot out of compliance with the zoning bylaw, it needs to be rezoned as business, the same as the Library (and rest of the block). This was the only question before Town Meeting: a vote on a zoning change to the Museum property, necessitated by technical requirements of the bylaw itself.

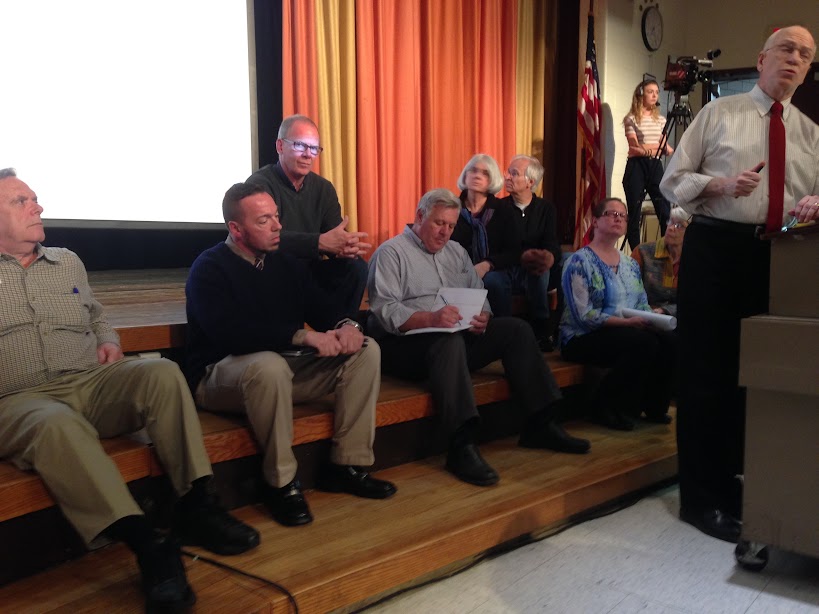

|

| The Library made a political faux pas in bringing a large contingent to the stage at Town Meeting, though only a few actually spoke to the article (here: architect John Kuhn) |

Opposition derived from:

- Hope of using this article to block the Library expansion plan.

- Concern that the rezoning, although required by law, might trigger undesirable further sale/commercial development of the History Museum property (a chimera: the Museum would never allow that to happen).

- Blowback against the Town Meeting Moderator (he had provided an unusually wide latitude for discussion of a similarly narrow article the previous week, so his attempt to limit discussion to the zoning change, without reference to the merits of the Library expansion plan that occasioned it, struck many in the chamber as inconsistent and unfair).

No, really: how bad was it?

How bad was it? People who read the newspaper accounts (1, 2) asked what in the world had happened, and I told them that "deeply divided and often contentious" could not begin to communicate the atmosphere and tone.

I have never seen so many protesting "points of order," even in this body known for its love of that that parliamentary procedure. (One senior, very dignified and polite member of the body later joked to me that we should just charge a fee for each point of order, so as to discourage the practice--or raise needed revenue.) In clear violation of the rules of the house, speakers interrupted and argued with the Moderator, signaled their approval or disapproval of statements by means of applause, hissing, catcalls, or other audible interjections, and impugned one another's motives and character.

One really has to watch the entire session to get the feel of the nastiness.

But this excerpt--in which a comment, limited by the rules of the house to 3 minutes, dragged on for 13 as a result of disagreement between speaker and Moderator--conveys the frustrating nature of the exchanges.

One observer charged that the "display of churlishness, no-nothingness, scorn, mockery and outright lies" would have been more appropriate to the Nazi Reichstag or the French Revolutionary legislature under The Terror. I actually received a number of sympathy notes from Town Meeting members as well as the general public. Even some of those on the winning side were embarrassed by the behavior of their allies.

Institutional suicide on live TV?

As I have more than once explained, I have always had mixed feelings about Town Meeting:

• On the one hand, real pride in our centuries-old democratic traditions, and real personal as well as political appreciation of the opportunity to learn the views of the most politically engaged fellow citizens.

• On the other hand, frustration with the process, by which I mean less the length and inefficiency of Town Meeting (which is the deliberately crafted curse of most democracy--here taken to an extreme, to be sure), and rather, the increasing difficulty of tackling any complex legislation in a body of some 250 people.

If it disappeared, I would, quite honestly, miss it: both because of the decline in participatory government, and because I genuinely enjoy the debate.

Whenever people talk about getting rid of Town Meeting, as I noted several years ago, I hear the voice of Michael Cann, a refugee from Nazi Germany and an ardent Town Meeting supporter. He had no illusions about the flaws of the institution but cautioned against abandoning it as earlier generations had overthrown "messy" democracy in the name of fascist "efficiency." Each step away from broad-based democracy, he warned, reduced the opportunities for public participation in government--and in the process, citizen interest in public affairs. We had already gone from a town meeting open to all, to an elected representative town meeting of 240, and now what: a council of a dozen or fewer members?

Michael died four years ago, and I was sad because I had lost a friend. It was sad but not tragic: part of the natural and inevitable order of things. By contrast, what we witnessed last week was both sadder and more tragic because it was unnecessary and entirely avoidable: a self-inflicted death. I am afraid that we saw Amherst Town Meeting commit political suicide on live television. It is hard to imagine how anyone watching could conclude this is a desirable or even functional form of government. The irony is that the people responsible for this spectacle thought they were saving the institution by fulfilling what they see as its aggressive watchdog role.

And the future: return to sanity or renewed mental torture?

Although this week's Town Meeting sessions included the remainder of the most controversial articles--even one directly opposing Library expansion (1, 2)--which generated their share of heat as well as light (and yes, just sheer wackiness), the conversation was nonetheless more civil and restrained. Several people I spoke with, who had been about to despair last week--even some harsh critics of Town Meeting--felt encouraged and buoyed as the night drew to a close on Wednesday. Perhaps there was hope after all. Others warned that the optimists were deluding themselves.

Was the bedlam of that Monday night an aberration or a glimpse of the future? I could not help but think of "The Fallen Sparrow" (1943), an underappreciated anti-fascist film about a Spanish Civil War veteran pursued by Nazis. In one of the most chilling scenes, the evil Dr. Skaas explains the essence of torture to the protagonist, who had experienced it firsthand in Spain. He contrasts the mere physical torture of the Ancients with the more sophisticated cruelty of Asia, epitomized by the infamous water torture, which combines the mental with the physical:

Dr. Skaas: Then—and here is the principle of all modern torture—release is given: the dripping is stopped, the victim is revived, just at the borderline of sanity. Then: ah, then, comes an interval during which the victim tortures himself—waiting, knowing that the operation will be repeated, and it is repeatable, most assuredly, with perhaps several new variations. You see the point?

Barby [the protagonist's girlfriend]: How perfectly ghastly!

Dr. Skaas: You see the beauty of the idea? Mental torture, in which the victim actively collaborates.

Town Meeting, too, "will be repeated . . . with perhaps several new variations." But which is the real Town Meeting? Is the torment really over, or was that just a momentary respite? I want to hope for the best, but in the meantime, we wait and worry.

Friday, April 1, 2016

Liberty, Government, and the Press in One Sentence

In the course of working on a revised version of an older essay on the history of periodicals, I had occasion to consider what sorts of documents or objects might illustrate it, so I'll share a few here.

autograph sentiment, 1878, from journalist and publisher Émile de Girardin (1802-81), whose conservative La Presse (1836) introduced the penny newspaper to France. He later moved toward the center of the political spectrum, turning against Napoleon III and opposing the forces of reaction under the Third Republic.

* * *

“Where liberty does not reign, it is fear that governs”

autograph sentiment, 1878, from journalist and publisher Émile de Girardin (1802-81), whose conservative La Presse (1836) introduced the penny newspaper to France. He later moved toward the center of the political spectrum, turning against Napoleon III and opposing the forces of reaction under the Third Republic.

Monday, February 22, 2016

Schiller and Lotte: postcard commemorating a poetic marriage, 1905

Authors' marriages deserve to be a subject of study in their own right, if only because they tended to loom so large in the bourgeois literary histories and biographies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The German equivalent to the marriages of Percy Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin or Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody is arguably that of Friedrich Schiller and Charlotte von Lengenfeld, often held up (and sentimentalized) as the ideal literary union and model of domesticity.

The third in a series of six postcards depicting the Schiller's life, issued on the centennial of his death in 1905, this one is entitled, "Own Home."

Chronicle of a wedding

As for the wedding itself, Gero von Wilpert's Schiller-Chronik, issued in anticipation of the Schiller bicentennial (Stuttgart, 1958) provides a convenient summary of the big day:

Undivided attention

Because the card dates from 1905 and was thus produced before the major change of 1907, it has no divided back in the fashion to which we are accustomed, i.e. space for the address at right and message at left. The reverse side informs the purchaser, "This side for the address only." People either sent cards without messages--the image alone serving as the greeting--or scrawled them on or around the illustration on the front, as best they could, for example, on this card celebrating Schiller's birthplace of Marbach am Neckar, from 1896:

If you're curious about the postal rates for the wedding card, they were even provided for the writer: "U S, Canada and Mexico 1 c. Foreign 2 c."

That the language is English and currency is American raises another issue: Although most of the Schiller anniversary cards were of course produced in Germany for Germans, not a few emanated from the United States. The publisher's imprint on this one reads, "A. Selige. Pub. Souv. Post Cards. St. Louis." Missouri was one of several centers of German settlement. The firm of Adolph Selige, active from 1900 to 1920, produced mainly cards on western or midwestern themes, so this one was intended for a more specialized audience, thanks to the large population of German immigrants or citizens of German origin. A useful reminder of the ever-evolving definitions of "American" identity and multicultural politics, among other things.

The German equivalent to the marriages of Percy Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin or Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody is arguably that of Friedrich Schiller and Charlotte von Lengenfeld, often held up (and sentimentalized) as the ideal literary union and model of domesticity.

The third in a series of six postcards depicting the Schiller's life, issued on the centennial of his death in 1905, this one is entitled, "Own Home."

• At right, we see a portrait of "Friedrich Schiller, Professor of History in Jena 1789-1799."The center vignettes depict, respectively, the church in which they were married and their first house:

• At left, "Schiller's spouse Charlotte, née von Lengenfeld. Born 22 Nov. 1766, died 9 July 1826."

• Church in Wenigenjena*) Schiller married here 22 February 1790.It is of course indicative of the time and place that Charlotte is here generally referred to only as Schiller's wife, and indeed, that the description of the wedding mentions only "Schiller" getting married. Times were indeed different.

• Schiller-house in Bad Lauchstädt*) Betrothal in Lauchstädt 3 August 1789

*) after drawings by Schiller's spouse

Chronicle of a wedding

As for the wedding itself, Gero von Wilpert's Schiller-Chronik, issued in anticipation of the Schiller bicentennial (Stuttgart, 1958) provides a convenient summary of the big day:

February 22. Wedding day. Early with Charlotte and Karoline to Kahla, where the mother-in-law is picked up around 10-11; from there around 2 directly to Wenigenjena (arrival around 5), where around 5:30 the wedding quietly took place under the direction of the Kantian theologian Adjunct G. L. Schmid in the presence of only the mother- and brother-in-law, so as to foil all the attempted surprises on the part of students and professors. Following this, return to Jena, where the evening is spent in tea-drinking and conversation. _-- Frau von Lengenfeld gives the couple a space of their own, but it is not yet an independent household, and rather, just a few additional rented rooms, and they still take their midday meal with Frau Schramm, Lotte employs a maid, Schiller, a manservant. -- The mother-in-law stays another 8 days, Karoline approximately 5 weeks in Jena with Fräulein von Seegner. Apart from that a solitary life, closer association only with Prof. Paulus.

Undivided attention

Because the card dates from 1905 and was thus produced before the major change of 1907, it has no divided back in the fashion to which we are accustomed, i.e. space for the address at right and message at left. The reverse side informs the purchaser, "This side for the address only." People either sent cards without messages--the image alone serving as the greeting--or scrawled them on or around the illustration on the front, as best they could, for example, on this card celebrating Schiller's birthplace of Marbach am Neckar, from 1896:

If you're curious about the postal rates for the wedding card, they were even provided for the writer: "U S, Canada and Mexico 1 c. Foreign 2 c."

That the language is English and currency is American raises another issue: Although most of the Schiller anniversary cards were of course produced in Germany for Germans, not a few emanated from the United States. The publisher's imprint on this one reads, "A. Selige. Pub. Souv. Post Cards. St. Louis." Missouri was one of several centers of German settlement. The firm of Adolph Selige, active from 1900 to 1920, produced mainly cards on western or midwestern themes, so this one was intended for a more specialized audience, thanks to the large population of German immigrants or citizens of German origin. A useful reminder of the ever-evolving definitions of "American" identity and multicultural politics, among other things.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

A Merry Christmas from Maximilien Robespierre (with a side-note on that Newton business)

From the vaults via last year's Tumblr post:

Understandably enough, we tend to think of December 25 primarily as Christmas, thereby ignoring or forgetting other events that occurred on that date. Among the latter is the birthday of Isaac Newton (1642).

Neil deGrasse Tyson caused a stink this year when he made what he thought was a witty tweet about this coincidence and aroused the ire of some who thought he was anti-Christian. In fact, he was doing nothing new or particularly clever: advocates of science have for some years promoted celebration of the 25th as Newton’s birthday as a light-hearted way of increasing awareness of scientific knowledge.

I always honor the birthday of the scientific revolutionary Newton, but also the occasion of a major address by the political revolutionary Robespierre.

read the rest

Understandably enough, we tend to think of December 25 primarily as Christmas, thereby ignoring or forgetting other events that occurred on that date. Among the latter is the birthday of Isaac Newton (1642).

Neil deGrasse Tyson caused a stink this year when he made what he thought was a witty tweet about this coincidence and aroused the ire of some who thought he was anti-Christian. In fact, he was doing nothing new or particularly clever: advocates of science have for some years promoted celebration of the 25th as Newton’s birthday as a light-hearted way of increasing awareness of scientific knowledge.

I always honor the birthday of the scientific revolutionary Newton, but also the occasion of a major address by the political revolutionary Robespierre.

read the rest

Labels:

Book History,

France,

French Revolution,

History and Science,

Holidays,

Religion

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Christmas greetings! (and two eighteenth-century prints of the nativity)

Wishing a merry Christmas to all my readers who celebrate the holiday.

From the vaults:

Artifact of the Moment: Reflections on Nativity Scenes in Two Eighteenth-Century German Bibles

Labels:

Art,

Book History,

From Habent Sua Fata Libelli,

Holidays,

Religion

Thursday, July 16, 2015

Ramadan Kareem, Eid Mubarak

As in many other aspects of life, I find that, as soon as July 4th has passed, the summer starts to vanish before my eyes, and I am behind in many tasks.

Among them this year is extending Ramadan greetings to my Muslim friends and readers. The holy month is almost ended.

Ramadan kareem.

Eid mubarak.

Bayramınız kutlu olsun.

Because we just marked the Laylat al-Qadr (or Night of Power), on which, according to tradition, the first verses of the Qur'an were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad, I decided to use for this year's image a photo of a Qur'an page that we keep in our living room. It is one of my sentimental favorites: among the handful of items that I purchased with my hard-earned pennies when, as a high school student, I first visited some classic bookstores in Greenwich Village.

The dealer told me that it was made in Jerusalem in the eighteenth century, but the style and paper clearly mark it as nineteenth-century (even at that age, I knew enough to be suspicious: but I am assuming he in his haste simply confused 1800s and 18th-century, as many educated people are wont to do, even today).

Wishing you all the blessings of the holy month.

My Ramadan posts from previous years.

Sunday, March 22, 2015

"To build a sustainable, climate-resilient future for all, we must invest in our world's forests. That will take political commitment at the highest levels, smart policies, effective law enforcement, innovative partnerships and funding."

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

March 21 is the International Day of Forests.

In celebration of that event, some tree- and forest-themed bookplates over on the book blog, habent sua fata libelli.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Happy Dictionary Day

Dictionary Day is the anniversary of Noah Webster's birthday, for good reason.

I am remiss in not having gotten my full-fledged post up for Mr. Webster's birthday (it turned out some extra work is required), but in order to honor (or placate) his spirit, I have uploaded a large new scan of a portrait engraving from his lifetime, over on the Tumblr.

Stay tuned for more in the near future.

I am remiss in not having gotten my full-fledged post up for Mr. Webster's birthday (it turned out some extra work is required), but in order to honor (or placate) his spirit, I have uploaded a large new scan of a portrait engraving from his lifetime, over on the Tumblr.

Stay tuned for more in the near future.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Un-bombs (1)

Ever since Isaiah had a vision of men beating their swords into ploughshares, it has been pleasant to imagine or witness other examples of the tools or symbols of war being converted into those of peace. I've posted a few examples over on the Tumblr.

Books, not bombs

Books, not bombs

Monday, September 24, 2012

Wishing You a Pleasant 5773! (holiday greetings then and now)

A very happy 5773 to those celebrating Rosh Hashanah this year.

Or, as David Letterman said last year:

Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year (literally: head of the year), is an intriguing holiday for a number of reasons. To begin with (no pun intended), it falls not in the first month of the year, but the seventh, and is seen as the "birthday of the world": just one of four types of new years in the calendar. The name Rosh Hashanah as such does not occur in the Torah, which instead describes the day as "a solemn rest unto you, a memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns, a holy convocation." It is thus akin to the Sabbath, in addition marked by sacrifice and the blowing of the shofar, or ram's horn (1, 2) . (Many other customs and rituals evolved in the intervening centuries.) In addition, though, it constitutes the beginning of a period of introspection, repentance, and charity culminating in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. These ten days are referred to as the "Days of Awe" and thus bear a certain resemblance to Ramadan, which is in a sense historically derived from them.

As I noted last year:

As chance would have it, such holiday greetings, personal as well as political, were the subject of several good articles in recent days.

In the cards

Hezi Amior, Israel Collection Curator at the National Library of Israel, traces the history of the Rosh Hashanah greeting. The first documented instance dates to fourteenth-century Germany. By the eighteenth century, the custom had spread to the new center of gravity of Ashkenazi Jewry in Eastern Europe. The development of the modern postal service coupled with new technologies of graphic reproduction in the late nineteenth century brought about the triumph of the greeting card in the age of mass print culture. In fact, he says, during the two decades before the end of World War I, "the vast majority of the mail sent by Jews in Europe and America consisted of New Year cards." They loomed large in the volume of mail in Mandatory Palestine and the new State of Israel, too, until the rise of the residential telephone and mass media in the 1970s finally led to the decline of the century-old practice and print genre.

Not surprisingly, as in other cases, the content of the cards reflected the very contemporary concerns of the societies in which they were produced. There were of course traditional religious and historical motifs. With the rise of political Zionism, the cards, around the world and particularly in the Land of Israel:

Following the War of Independence, and "especially between the Six-day War and the Yom Kippur War," the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) featured prominently in such greetings, often depicted at holy sites. In this 1967 example: victorious soldiers rejoicing at the Western Wall in Jerusalem (which Jews had been forbidden to visit since 1949 under the Jordanian occupation):

As Amior observes, "these greeting cards recall a time of ideological unity and naïve and uninhibited national pride" in a nation still under construction.

Sacred, secular, and socialist

Matti Friedman, one of my favorite journalists over at The Times of Israel (full disclosure: I write for that publication, too), has a fine piece on a subset of this cultural tradition: "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah." Few concepts cause more confusion than the notion of a "Jewish state." The typical American or other outsider, unfamiliar with an identity that comprises an ethnicity as well as a religion, mistakenly tends to assume that it either cannot dispense with or involves only the latter. Many of the early Zionists were not religiously observant, but they often drew upon elements of tradition in their efforts to create a "secular Judaism," a concept that is therefore perfectly logical in this context but may sound strange in others (it's virtually impossible to imagine a "secular Christian" culture).

Matti's article tells the story of these efforts by "the deeply spiritual socialists who were responsible, more than any other single group of people, for creating the state of Israel." He focuses on The Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture at Kibbutz Beit Hashita, whose archives "cover the better part of a century of Jewish holiday celebrations but are entirely uninterested in God, rabbis or law."

Several cultural organizations, including the National Yiddish Book Center on the campus of Hampshire College here in Amherst and the Magnes Museum in Berkeley, have resurrected and updated the old traditions by allowing web visitors to send e-greetings of vintage cards. A few examples from the Magnes:

Still, my favorite, which perfectly captures the combination of spiritual and secular, observance and irreverence, has to be this one. As a window into a cultural mindset, it just says it all.

I'm all out, so I'll stop here.

Resources

• Last year's post

• Hemi Amior, "Shana Tova from Alfred Dreyfus," Ynet News, 17 September 2012

• "Rosh Hashana Greeting Cards in Jewish and Israeli Tradition," from National Library of Israel (a fuller range of examples, from which Amior selected his illustrations)

• Matti Friedman, "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah," Times of Israel, 16 Sept. 2012

• Ben Sales, "The un-Orthodox approach to Yom Kippur in Israel," 23 Sept. 2012

• Miriam Kresh, "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Green the World," Green Prophet, 23 Sept. 2012

• Yaakov Lozowick, "Jewish New Year Greeting Exchanges From Presidents Carter and Reagan and Israeli Prime Minister Begin," Israel's Documented Story, 20 Sept. 2012

• "Rosh Hashanah E-Cards from the Magnes Museum," The New Centrist, 9 Sept. 2009

Or, as David Letterman said last year:

It's Jewish year 5772, and all day I've been writing 5771 on my checks. That's the 30th consecutive year I've told that joke.

Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year (literally: head of the year), is an intriguing holiday for a number of reasons. To begin with (no pun intended), it falls not in the first month of the year, but the seventh, and is seen as the "birthday of the world": just one of four types of new years in the calendar. The name Rosh Hashanah as such does not occur in the Torah, which instead describes the day as "a solemn rest unto you, a memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns, a holy convocation." It is thus akin to the Sabbath, in addition marked by sacrifice and the blowing of the shofar, or ram's horn (1, 2) . (Many other customs and rituals evolved in the intervening centuries.) In addition, though, it constitutes the beginning of a period of introspection, repentance, and charity culminating in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. These ten days are referred to as the "Days of Awe" and thus bear a certain resemblance to Ramadan, which is in a sense historically derived from them.

German Jews at prayer on Yom Kippur in the 18th century

As I noted last year:

The image of the divine particular to this season (and especially interesting from the standpoint of book history) is that of God as scribe or bookkeeper, keeping records and rendering judgment on the lives of individuals in various heavenly ledgers and archives. According to the rabbinic interpretation, he records the judgment for the preceding year on Rosh Hashanah, but the verdict is not final until it is "sealed" on Yom Kippur. Thus, the emphasis is on constant repentance during the ten days. Prayer, repentance, and good deeds, it is said, can still avert a negative judgment up to the moment that the gates of judgment close at the end of the Day of Atonement.As has been the custom, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas sent greetings to Israel's President Shimon Peres: "Happy holiday and a Happy New Year to you and the entire Israeli nation." He also expressed the desire of the Palestinian people for peace, and the hope that the new year might bring steps in that direction. Peres, for his part, replied, "I know the past year has been a difficult year, but we mustn't give up… we must continue to strive for peace." In a separate Facebook message to the wider public, he said, “Peace is the greatest blessing to our children,” and warned against intolerance: “Don’t put up with racism or violence of any kind, with religious or political extremism, or discrimination based on race or gender.”

Accordingly, the traditional greetings for the New Year and Days of Awe are:

From Rosh Hashahah through Yom Kippur:

Shana tova: a good yearLeading up to/through Yom Kippur:

L'shanah tova tikatevu v'tichatemu: May you be inscribed and sealed [in the Book of Life] for a good year

G'mar chatima tova: roughly, May you be sealed [in the Book of Life] for a good year [literally just: a good sealing]

As chance would have it, such holiday greetings, personal as well as political, were the subject of several good articles in recent days.

In the cards

Hezi Amior, Israel Collection Curator at the National Library of Israel, traces the history of the Rosh Hashanah greeting. The first documented instance dates to fourteenth-century Germany. By the eighteenth century, the custom had spread to the new center of gravity of Ashkenazi Jewry in Eastern Europe. The development of the modern postal service coupled with new technologies of graphic reproduction in the late nineteenth century brought about the triumph of the greeting card in the age of mass print culture. In fact, he says, during the two decades before the end of World War I, "the vast majority of the mail sent by Jews in Europe and America consisted of New Year cards." They loomed large in the volume of mail in Mandatory Palestine and the new State of Israel, too, until the rise of the residential telephone and mass media in the 1970s finally led to the decline of the century-old practice and print genre.

Not surprisingly, as in other cases, the content of the cards reflected the very contemporary concerns of the societies in which they were produced. There were of course traditional religious and historical motifs. With the rise of political Zionism, the cards, around the world and particularly in the Land of Israel:

feature central Zionist values, such as agricultural labor, a return to Biblical paradigms, the local landscape, cultural and economic undertakings, milestones in reclaiming the land and founding of state institutions, the immigration struggle, the Haganah ("The Defense"), the settlement movement, and so forth.

| Captain Alfred Dreyfus, famed victim of antisemitism at the turn of the century |

[source]

| pioneers in the old-new land: "Those who sow with tears will reap with songs of joy" |

[source]

Following the War of Independence, and "especially between the Six-day War and the Yom Kippur War," the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) featured prominently in such greetings, often depicted at holy sites. In this 1967 example: victorious soldiers rejoicing at the Western Wall in Jerusalem (which Jews had been forbidden to visit since 1949 under the Jordanian occupation):

[source]

As Amior observes, "these greeting cards recall a time of ideological unity and naïve and uninhibited national pride" in a nation still under construction.

Sacred, secular, and socialist

Matti Friedman, one of my favorite journalists over at The Times of Israel (full disclosure: I write for that publication, too), has a fine piece on a subset of this cultural tradition: "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah." Few concepts cause more confusion than the notion of a "Jewish state." The typical American or other outsider, unfamiliar with an identity that comprises an ethnicity as well as a religion, mistakenly tends to assume that it either cannot dispense with or involves only the latter. Many of the early Zionists were not religiously observant, but they often drew upon elements of tradition in their efforts to create a "secular Judaism," a concept that is therefore perfectly logical in this context but may sound strange in others (it's virtually impossible to imagine a "secular Christian" culture).

Matti's article tells the story of these efforts by "the deeply spiritual socialists who were responsible, more than any other single group of people, for creating the state of Israel." He focuses on The Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture at Kibbutz Beit Hashita, whose archives "cover the better part of a century of Jewish holiday celebrations but are entirely uninterested in God, rabbis or law."

“For the first pioneers Judaism was very important, in addition to the ideology of returning to the land of the Bible, working the fields, agriculture, socialism, and humanistic values,” said Mordy Stein, one of the teachers at the institute. “In essence, they were creating the new Jew – the old Jew, the Diaspora Jew, was what they were rejecting, and they rejected Diaspora religion because it represented the old Jew.

“They didn’t want rabbinic Judaism, because they identified it almost mathematically with Exile. They wanted new ways of expressing Jewish values and holidays according to their new understandings about the new Jew, so they started to create traditions that were much closer to the biblical concept, the agricultural concept, the natural feeling of a Jew living in the land of Israel on the land, which had been forgotten over 2,000 years,” Stein said.

As Institute founder Aryeh Ben-Gurion (nephew of the first prime minister) characterized Rosh Hashanah: "These are borderline days between the end of summer, the season of

death in the universe, and a new birth, the beginning of a new life

cycle in nature and agriculture and new relations between the sky and

the earth, between rain and soil." One of the typical cards from the pre-statehood 1940s thus emphasizes the synthesis of nature and culture: the sun of the seasons, bringing forth crops and heralding a national rebirth as it shines down upon a new agricultural commune protected by characteristic fence and watchtower.

As is often the case, perspectives change, and the Institute in the meantime includes some traditional prayer in its contemporary liturgies and educational materials. As Matti puts it, "God is no longer taboo." He also suggests that the Institute's program and vision are not passé. He concludes by noting that, although the pure socialism of the kibbutz movement now seems a historic artifact, its approach to the holidays just might have a future among the many people who value ritual and tradition and crave community but are unwilling to cede the definition and practice of religion to the Orthodox.

The solemn day of Yom Kippur is, or used to be, the one holiday that most Jews, however, lax or secular in their practice, tend to observe in some fashion. In fact, it has been said, this was one reason it was relatively easy to launch an emergency call-up of Israel's reserves when Arab armies launched their surprise attack in 1973: one knew where to find the troops. Had the attack come on Rosh Hashanah, they would have been dispersed around the country on picnics and other outings. (New revelations about the intelligence and communications failures on the eve of the war came from the archives just this past week.)

Still, as a story in today's Times of Israel notes, even those who mark the holiday in some form or fashion may not do so in traditional ways. Many secular Israelis may attend the opening evening service and then go cycling the next day rather than attend hours of services with which they are not familiar or comfortable. The article describes various organizations that, akin to the Kibbutz Institute, are attempting to craft meaningful forms of engagement with the holiday for the non-observant: including secular study of religious texts, liturgy drawing upon contemporary literature and music, confessional services "focusing on community and nation," and commemorations of the 1973 war.

As author Ben Sales notes, "Yom Kippur lacks an element of national heroism central to such holidays as Chanukah and Purim, which many secular Israelis observe," but "the ideas of self-improvement and forgiveness should resonate with everyone." In other ways, it is therefore easy to integrate the observance of Yom Kippur into modern secular sensibilities and lifestyles. "Green Prophet," an environmental organization that calls itself a "sustainable voice for green news on the Middle East" from all peoples and faiths in the region, offers tips to "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Help Green the World."

Eventually, the standoff in the years after the Yom Kippur War led to the breakthrough that began the long, torturous, and still incomplete "peace process." As the example of Presidents Abbas and Peres reminds us, political leaders as well as individuals often exchange holiday greetings. The excellent new Israel Archives blog of State Archivist Yaakov Lozowick has been releasing a steady stream of new material. Last week, it shared exchanges of New Year greetings between Presidents Carter and Reagan and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Responding to Carter's holiday wishes in 1979, Begin wrote:

As is often the case, perspectives change, and the Institute in the meantime includes some traditional prayer in its contemporary liturgies and educational materials. As Matti puts it, "God is no longer taboo." He also suggests that the Institute's program and vision are not passé. He concludes by noting that, although the pure socialism of the kibbutz movement now seems a historic artifact, its approach to the holidays just might have a future among the many people who value ritual and tradition and crave community but are unwilling to cede the definition and practice of religion to the Orthodox.

The solemn day of Yom Kippur is, or used to be, the one holiday that most Jews, however, lax or secular in their practice, tend to observe in some fashion. In fact, it has been said, this was one reason it was relatively easy to launch an emergency call-up of Israel's reserves when Arab armies launched their surprise attack in 1973: one knew where to find the troops. Had the attack come on Rosh Hashanah, they would have been dispersed around the country on picnics and other outings. (New revelations about the intelligence and communications failures on the eve of the war came from the archives just this past week.)

Still, as a story in today's Times of Israel notes, even those who mark the holiday in some form or fashion may not do so in traditional ways. Many secular Israelis may attend the opening evening service and then go cycling the next day rather than attend hours of services with which they are not familiar or comfortable. The article describes various organizations that, akin to the Kibbutz Institute, are attempting to craft meaningful forms of engagement with the holiday for the non-observant: including secular study of religious texts, liturgy drawing upon contemporary literature and music, confessional services "focusing on community and nation," and commemorations of the 1973 war.

As author Ben Sales notes, "Yom Kippur lacks an element of national heroism central to such holidays as Chanukah and Purim, which many secular Israelis observe," but "the ideas of self-improvement and forgiveness should resonate with everyone." In other ways, it is therefore easy to integrate the observance of Yom Kippur into modern secular sensibilities and lifestyles. "Green Prophet," an environmental organization that calls itself a "sustainable voice for green news on the Middle East" from all peoples and faiths in the region, offers tips to "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Help Green the World."

Eventually, the standoff in the years after the Yom Kippur War led to the breakthrough that began the long, torturous, and still incomplete "peace process." As the example of Presidents Abbas and Peres reminds us, political leaders as well as individuals often exchange holiday greetings. The excellent new Israel Archives blog of State Archivist Yaakov Lozowick has been releasing a steady stream of new material. Last week, it shared exchanges of New Year greetings between Presidents Carter and Reagan and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Responding to Carter's holiday wishes in 1979, Begin wrote:

In accordance with the ancient calendar the year 5739 had ended and, in ushering in the New Year 5740 we pray that it may, indeed, be blessed. The twelve months gone by will be remembered as the year in which the Camp David agreement was concluded and the treaty of peace between Israel and Egypt was signed. And as you rightly state, Mr. President: 'This new year finds the ties between our two countries stronger than ever.'What a difference three decades make. But on to lighter topics.

Several cultural organizations, including the National Yiddish Book Center on the campus of Hampshire College here in Amherst and the Magnes Museum in Berkeley, have resurrected and updated the old traditions by allowing web visitors to send e-greetings of vintage cards. A few examples from the Magnes:

[source]

[source]

Still, my favorite, which perfectly captures the combination of spiritual and secular, observance and irreverence, has to be this one. As a window into a cultural mindset, it just says it all.

I'm all out, so I'll stop here.

Resources

• Last year's post

• Hemi Amior, "Shana Tova from Alfred Dreyfus," Ynet News, 17 September 2012

• "Rosh Hashana Greeting Cards in Jewish and Israeli Tradition," from National Library of Israel (a fuller range of examples, from which Amior selected his illustrations)

• Matti Friedman, "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah," Times of Israel, 16 Sept. 2012

• Ben Sales, "The un-Orthodox approach to Yom Kippur in Israel," 23 Sept. 2012

• Miriam Kresh, "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Green the World," Green Prophet, 23 Sept. 2012

• Yaakov Lozowick, "Jewish New Year Greeting Exchanges From Presidents Carter and Reagan and Israeli Prime Minister Begin," Israel's Documented Story, 20 Sept. 2012

• "Rosh Hashanah E-Cards from the Magnes Museum," The New Centrist, 9 Sept. 2009

Labels:

Book History,

Historical Anniversaries,

Middle East,

Religion,

Socialism

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)