When British General Allenby entered Jerusalem as conqueror in December 1917, he made a point of doing so on foot.

Full original post.

"In fiction, the principles are given, to find

the facts: in history, the facts are given,

to find the principles; and the writer

who does not explain the phenomena

as well as state them performs

only one half of his office."

Thomas Babington Macaulay,

"History," Edinburgh Review, 1828

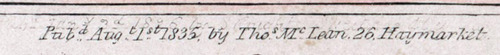

{enlarge}Etching with hand coloring.

{enlarge}Not yet "Victorian” in the strict (or any other) sense, the etching nonetheless lacks the ribaldry or bite of Cruikshank’s other early (especially political) work: it manages to be satirical and sentimental at once. We can already recognize in it our received image of Christmas as domestic idyll, familiar from Dickens to “The Nutcracker” (though the evolution of the latter is a tale in itself).

|

| (late 19th-century engraving) |

On a visit to the site during those renovations I discovered a story that wasn’t known until then, regarding the Jewish-Ottoman-Palestinian connection to the mosques on Temple Mount.

Story of the iron panel

The Dome of the Rock was surrounded with scaffolding, and before ascending one of them a friend of mine drew my attention to an iron panel that lay on the floor and was inscribed in French. The foreman of the Irish construction company said the panel had been found between the two halves of the crescents at on top of the mosque, and was temporarily dismantled so that the dome could be coated in gold.

The words in French revealed that the Mosque had been renovated in 1899 during Turkish rule, and that the works had been assisted by the Jewish community in Jerusalem led by a public figure called Avraham (Albert) Entebbe, who among his numerous other activities was also the principal of the city's "Kol Israel Haverim" school.

Entebbe, who was the undersigned on the French inscription, was known for his courageous ties with the heads of the Ottoman rule, and the inscription noted that for the purpose of renovating the mosques on the Temple Mount five acclaimed Jewish artists had been invited to Jerusalem. The Jewish stone carvers, wood carvers and iron mongers from various cities in the Mediterranean basin, shared their skills with their Muslim brothers during months of work.

Zenith of Jewish-Muslim cooperation

The inscription also noted that all the students at Entebbe's school were given a three-month leave in order to assist their Muslim brothers in the renovations works on Temple Mount. In the last lines of the inscription, Entebbe described the ideal cooperation and understanding that prevailed between Jews and Muslims in the Holy City, which reached its zenith when the Jews undertook renovations of the Temple Mount mosques in 1899.

|

| Palmesel (15th-century Germany), The Cloisters |