It's hard to recall exactly how I first learned of the "

Japanese internment." That is, I know I first learned of it from my parents when I was a schoolchild, but it is the context that escapes me.

On the one hand, my parents told me of Quaker friends in the Twin Cities who had been conscientious objectors and somehow assisted Japanese Americans in that era. On the other hand, my clearest memory is of my parents' conversations with Japanese-American friends in Madison who had been interned, in the

Manzanar and

Jerome (Arkansas) camps, respectively.

Paul Kusuda, later the Deputy Director of the Bureau of Juvenile Services for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, became one of my father's first colleagues and closest friends when we moved to Madison. Early on, he and his wife Atsuko invited us over to dinner (for some reason, I recall that it was the first time I encountered zucchini). It was a perfect pairing: both husbands worked for State social services, and both wives were librarians--and their son (also named Jim) and I discovered a common interest in hiking, fishing, and the outdoors. In addition, it turned out that Paul and my father had much to share with one another as they compared their experiences of discrimination in the US and Europe during the wartime years.

Especially after retirement, Paul dedicated his time to groups working on behalf of Asian Americans and civil rights, and in particular to the

quest for US acknowledgement of the wrongs done by the internment. He served as Chair of the Wisconsin Organization of Asian Americans and at age 92 is still a regular columnist for

Asian Wisconzine.

Dedication to the highest ideals of this country

Among the things that impressed me most about Paul were his even temperament, relentlessly calm and thoughtful approach to all aspects of life, and sense of humor (which not only extended to but in fact began with himself). He was the

recipient of multiple awards for his activism on behalf of civil rights as well as for his professional work. The citation accompanying his 2006

Dane County Martin Luther King, Jr. Award read:

Mr. Kusuda was in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II. Instead of allowing that unfortunate and painful experience to make him bitter, Paul Kusuda has worked hard to heal those wounds by working very hard with the Japanese American Citizens League of Wisconsin and other organizations - - a labor of strength, dedication to the highest ideals of this country, and forgiveness that is consistent with Martin Luther King’s insistence that we must not succumb to the poison of hate.

His utter refusal to become bitter is indeed one of the hallmarks of his character. During his internment and afterward, he was never one of the radicals.

As he later explained, as a loyal citizen and believer in the rule of law, he saw it as his duty not to resist the internment order, but to challenge it through peaceful remonstrance and questioning.

Still, his quiet anger at the injustice came through at the time and in his recollections. Fighting poverty in a rough Los Angeles neighborhood, he had managed to start taking college courses in engineering. Ironically, he received his acceptance as a naval ordnance inspector for the San Francisco shipyards at the beginning of December 1941. A week later, it was rescinded without explanation, though none was needed. In February came the notorious

Executive Order 9066, but he was certain that, as a loyal American, he would not be rounded up. In April, the family was given a week's notice for

relocation to Manzanar. The disappointment was harsh.

Why was it that we were . . . singled out . . . ?

As

he recalled,

We were at war with Germany, Italy, and Japan (Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941). Yet, only persons of

Japanese ancestry were uprooted as a group and forcibly evacuated from the west coasts of California,

Oregon, and Washington. Of the approximately 120,000 persons involved, two-thirds were American citizens, euphemistically called non-aliens. Only persons of Japanese ancestry were summarily, without trial or allegation, removed from the West Coast. Persons of German or Italian ancestry were individually identified, and if determined to be of possible danger to our country, sent to internment camps.

His typed and handwritten letters (many on file in the

Japanese American National Museum) reflect his growing disillusionment. In

May 1942, he wrote to his teacher and supporter,

Mrs. Afton Dill Nance:

My morale isn’t really low. From now on, I’m not going to trust anyone when it comes to governmental affairs. To think that I got faily [sic] good grades in civics, American History, Political Science, etc., makes me laugh because Ireall [sic] believed in all that I studied. Maybe this darn bitterness will work off – I hope so. Anyway, I’m waiting for something so that I can again cling to to all that America means to me. I guess that at the present time, I’m in the throes of meloncholia [sic] or something. Perhaps that may be changed. Ihope [sic] that it will change for the better soon.

Here is something to think about --- it made me think for quite a bit. A sentry shot a kid of about 17 or 18 for crossing a line when the former soldier on watch gave the youngster permission to cross the sentry line. What kind of a deal is it when even kids are shot for such a minor infraction of rules. Darn it all, I’m really disgusted with it all.

Hasta la vista,

Paul H.

And a week later:

Time and time again, I have argued that America is not a democracy for white people only. Was I wrong? God help us all if I am or was because what a future is in store for everyone in a false democracy!

Angered that the draft classifications of all Japanese Americans had been changed from 1-A to 4-C,

he also wrote to President Roosevelt, asking why the Japanese Americans were singled out as untrustworthy, and insisting on the right to be allowed to fight:

Dear Mr. President:

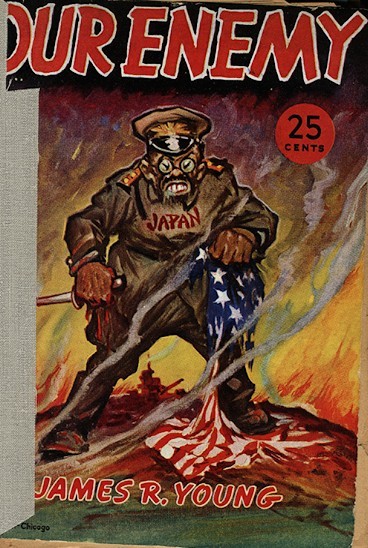

As you know, persons of Japanese parentage have been

evacuated from the western coastal regions of the United States.

Many of us do not know exactly why we were sent out of those

areas, although numerous attempts have been made to justify such

action. However, we are anxious to comply with all the govern-

mental regulations which may be established.

The greater majority of the Japanese people in the

United States are whole-heartedly for ultimate victory of the

Allied Nations, and yet, we are referred to as "Japs." That term

used in scorn is very hateful to us; many of us deem it an insult.

Not many people think enough to call us Americans.

In schools, everyone is taught that in the eyes of the

law, all persons are considered innocent until proven to be guilty.

But, why was it that we were branded as potential spies we were

singled out as threatening democracy, we were and are considered

dangerous? That hurt! What cases of sabotage promoted by us can

be said to justify the up-rooting of our hard-earned way of living?

What can justify the fact that we Americans are not allowed to aid

in the war effort? What can justify the fact that many students

are cut off from education without reason? Is that at all fair?

Try as we may, the reasons cannot be found to answer such questions.

Now, it is too late to undo the harm created by the forced

evacuation, but we want you to realize that we are not saboteurs, we

are not axis [sic] agents, we are not "Japs." But, we are Americans.

Give us a real chance to prove ourselves.

Sincerely yours,

Paual H. Kusuda

B 19-9-2

Manzanar Reception Center

Manzanar, California

Paul Kusuda was lucky in that he spent only a year in the camp. At the beginning of 1943, the government changed its policy and decided to recruit Japanese Americans for the war effort. He was unsuccessful in enlisting, but he was allowed to go to Chicago to study social work, which he had in the meantime chosen over engineering as his future profession. (

How he doggedly tried to get into the Army before and after moving to Chicago makes for both sad and humorous reading.)

His continuing faith in the American system has not prevented him from criticizing subsequent government policy--from overreactions in the wake of the 9-11 attacks to the

invasion of Iraq--for he saw no contradiction in being

as concerned for civil liberties as security. As a profile in the

Madison Times put it:

Paul Kusuda is a law-abiding, Made in the USA, U.S. citizen. And Kusuda, a long-time Madison activist and retiree from the WI Division of Corrections, has some grave concerns about parts of the USA Patriot Act. He wonders about the two U.S. citizens who are currently being detained indefinitely at Guantanamo Bay without access to a lawyer or the courts. Theoretically speaking, they could be incarcerated there for the rest of their lives without ever having been charged with or convicted of a crime.

Kusuda wonders and is concerned because he's been there before. Kusuda is one of 120,000 Japanese Americans who were detained during World War II in relocation camps on the desert fringe in California without due process or having been accused of a crime. Kusuda knows how it feels.

Footnote

However I first learned of the internment, I soon read all I could on the subject, which in that day was not a great deal--e.g.

America's Concentration Camps,

Farewell to Manzanar, and

Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps--the topic was not nearly as well known as it is now. To give you a sense of how things have changed: when I was growing up, few children or adults knew about this shameful episode. Today, by contrast, and thankfully, it is so well known that, when I ask students what they first associate with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it is as likely to be the Japanese internment as the New Deal or the US to victory in World War II. An illustration of the mixed blessings of progress, if ever there was one.

A selection of Paul's columns on his life and issues of diversity:

* * *

Related posts on this blog: