Or, as David Letterman said last year:

It's Jewish year 5772, and all day I've been writing 5771 on my checks. That's the 30th consecutive year I've told that joke.

Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year (literally: head of the year), is an intriguing holiday for a number of reasons. To begin with (no pun intended), it falls not in the first month of the year, but the seventh, and is seen as the "birthday of the world": just one of four types of new years in the calendar. The name Rosh Hashanah as such does not occur in the Torah, which instead describes the day as "a solemn rest unto you, a memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns, a holy convocation." It is thus akin to the Sabbath, in addition marked by sacrifice and the blowing of the shofar, or ram's horn (1, 2) . (Many other customs and rituals evolved in the intervening centuries.) In addition, though, it constitutes the beginning of a period of introspection, repentance, and charity culminating in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. These ten days are referred to as the "Days of Awe" and thus bear a certain resemblance to Ramadan, which is in a sense historically derived from them.

German Jews at prayer on Yom Kippur in the 18th century

As I noted last year:

The image of the divine particular to this season (and especially interesting from the standpoint of book history) is that of God as scribe or bookkeeper, keeping records and rendering judgment on the lives of individuals in various heavenly ledgers and archives. According to the rabbinic interpretation, he records the judgment for the preceding year on Rosh Hashanah, but the verdict is not final until it is "sealed" on Yom Kippur. Thus, the emphasis is on constant repentance during the ten days. Prayer, repentance, and good deeds, it is said, can still avert a negative judgment up to the moment that the gates of judgment close at the end of the Day of Atonement.As has been the custom, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas sent greetings to Israel's President Shimon Peres: "Happy holiday and a Happy New Year to you and the entire Israeli nation." He also expressed the desire of the Palestinian people for peace, and the hope that the new year might bring steps in that direction. Peres, for his part, replied, "I know the past year has been a difficult year, but we mustn't give up… we must continue to strive for peace." In a separate Facebook message to the wider public, he said, “Peace is the greatest blessing to our children,” and warned against intolerance: “Don’t put up with racism or violence of any kind, with religious or political extremism, or discrimination based on race or gender.”

Accordingly, the traditional greetings for the New Year and Days of Awe are:

From Rosh Hashahah through Yom Kippur:

Shana tova: a good yearLeading up to/through Yom Kippur:

L'shanah tova tikatevu v'tichatemu: May you be inscribed and sealed [in the Book of Life] for a good year

G'mar chatima tova: roughly, May you be sealed [in the Book of Life] for a good year [literally just: a good sealing]

As chance would have it, such holiday greetings, personal as well as political, were the subject of several good articles in recent days.

In the cards

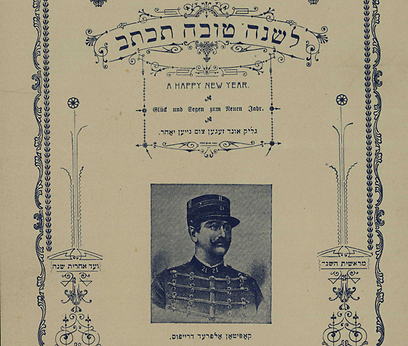

Hezi Amior, Israel Collection Curator at the National Library of Israel, traces the history of the Rosh Hashanah greeting. The first documented instance dates to fourteenth-century Germany. By the eighteenth century, the custom had spread to the new center of gravity of Ashkenazi Jewry in Eastern Europe. The development of the modern postal service coupled with new technologies of graphic reproduction in the late nineteenth century brought about the triumph of the greeting card in the age of mass print culture. In fact, he says, during the two decades before the end of World War I, "the vast majority of the mail sent by Jews in Europe and America consisted of New Year cards." They loomed large in the volume of mail in Mandatory Palestine and the new State of Israel, too, until the rise of the residential telephone and mass media in the 1970s finally led to the decline of the century-old practice and print genre.

Not surprisingly, as in other cases, the content of the cards reflected the very contemporary concerns of the societies in which they were produced. There were of course traditional religious and historical motifs. With the rise of political Zionism, the cards, around the world and particularly in the Land of Israel:

feature central Zionist values, such as agricultural labor, a return to Biblical paradigms, the local landscape, cultural and economic undertakings, milestones in reclaiming the land and founding of state institutions, the immigration struggle, the Haganah ("The Defense"), the settlement movement, and so forth.

|

| Captain Alfred Dreyfus, famed victim of antisemitism at the turn of the century |

[source]

|

| pioneers in the old-new land: "Those who sow with tears will reap with songs of joy" |

[source]

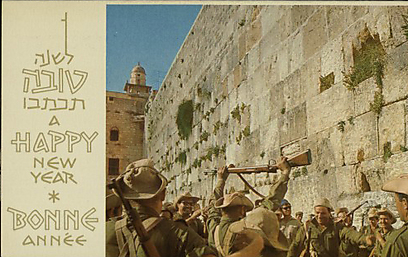

Following the War of Independence, and "especially between the Six-day War and the Yom Kippur War," the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) featured prominently in such greetings, often depicted at holy sites. In this 1967 example: victorious soldiers rejoicing at the Western Wall in Jerusalem (which Jews had been forbidden to visit since 1949 under the Jordanian occupation):

[source]

As Amior observes, "these greeting cards recall a time of ideological unity and naïve and uninhibited national pride" in a nation still under construction.

Sacred, secular, and socialist

Matti Friedman, one of my favorite journalists over at The Times of Israel (full disclosure: I write for that publication, too), has a fine piece on a subset of this cultural tradition: "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah." Few concepts cause more confusion than the notion of a "Jewish state." The typical American or other outsider, unfamiliar with an identity that comprises an ethnicity as well as a religion, mistakenly tends to assume that it either cannot dispense with or involves only the latter. Many of the early Zionists were not religiously observant, but they often drew upon elements of tradition in their efforts to create a "secular Judaism," a concept that is therefore perfectly logical in this context but may sound strange in others (it's virtually impossible to imagine a "secular Christian" culture).

Matti's article tells the story of these efforts by "the deeply spiritual socialists who were responsible, more than any other single group of people, for creating the state of Israel." He focuses on The Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture at Kibbutz Beit Hashita, whose archives "cover the better part of a century of Jewish holiday celebrations but are entirely uninterested in God, rabbis or law."

“For the first pioneers Judaism was very important, in addition to the ideology of returning to the land of the Bible, working the fields, agriculture, socialism, and humanistic values,” said Mordy Stein, one of the teachers at the institute. “In essence, they were creating the new Jew – the old Jew, the Diaspora Jew, was what they were rejecting, and they rejected Diaspora religion because it represented the old Jew.

“They didn’t want rabbinic Judaism, because they identified it almost mathematically with Exile. They wanted new ways of expressing Jewish values and holidays according to their new understandings about the new Jew, so they started to create traditions that were much closer to the biblical concept, the agricultural concept, the natural feeling of a Jew living in the land of Israel on the land, which had been forgotten over 2,000 years,” Stein said.

As Institute founder Aryeh Ben-Gurion (nephew of the first prime minister) characterized Rosh Hashanah: "These are borderline days between the end of summer, the season of

death in the universe, and a new birth, the beginning of a new life

cycle in nature and agriculture and new relations between the sky and

the earth, between rain and soil." One of the typical cards from the pre-statehood 1940s thus emphasizes the synthesis of nature and culture: the sun of the seasons, bringing forth crops and heralding a national rebirth as it shines down upon a new agricultural commune protected by characteristic fence and watchtower.

As is often the case, perspectives change, and the Institute in the meantime includes some traditional prayer in its contemporary liturgies and educational materials. As Matti puts it, "God is no longer taboo." He also suggests that the Institute's program and vision are not passé. He concludes by noting that, although the pure socialism of the kibbutz movement now seems a historic artifact, its approach to the holidays just might have a future among the many people who value ritual and tradition and crave community but are unwilling to cede the definition and practice of religion to the Orthodox.

The solemn day of Yom Kippur is, or used to be, the one holiday that most Jews, however, lax or secular in their practice, tend to observe in some fashion. In fact, it has been said, this was one reason it was relatively easy to launch an emergency call-up of Israel's reserves when Arab armies launched their surprise attack in 1973: one knew where to find the troops. Had the attack come on Rosh Hashanah, they would have been dispersed around the country on picnics and other outings. (New revelations about the intelligence and communications failures on the eve of the war came from the archives just this past week.)

Still, as a story in today's Times of Israel notes, even those who mark the holiday in some form or fashion may not do so in traditional ways. Many secular Israelis may attend the opening evening service and then go cycling the next day rather than attend hours of services with which they are not familiar or comfortable. The article describes various organizations that, akin to the Kibbutz Institute, are attempting to craft meaningful forms of engagement with the holiday for the non-observant: including secular study of religious texts, liturgy drawing upon contemporary literature and music, confessional services "focusing on community and nation," and commemorations of the 1973 war.

As author Ben Sales notes, "Yom Kippur lacks an element of national heroism central to such holidays as Chanukah and Purim, which many secular Israelis observe," but "the ideas of self-improvement and forgiveness should resonate with everyone." In other ways, it is therefore easy to integrate the observance of Yom Kippur into modern secular sensibilities and lifestyles. "Green Prophet," an environmental organization that calls itself a "sustainable voice for green news on the Middle East" from all peoples and faiths in the region, offers tips to "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Help Green the World."

Eventually, the standoff in the years after the Yom Kippur War led to the breakthrough that began the long, torturous, and still incomplete "peace process." As the example of Presidents Abbas and Peres reminds us, political leaders as well as individuals often exchange holiday greetings. The excellent new Israel Archives blog of State Archivist Yaakov Lozowick has been releasing a steady stream of new material. Last week, it shared exchanges of New Year greetings between Presidents Carter and Reagan and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Responding to Carter's holiday wishes in 1979, Begin wrote:

As is often the case, perspectives change, and the Institute in the meantime includes some traditional prayer in its contemporary liturgies and educational materials. As Matti puts it, "God is no longer taboo." He also suggests that the Institute's program and vision are not passé. He concludes by noting that, although the pure socialism of the kibbutz movement now seems a historic artifact, its approach to the holidays just might have a future among the many people who value ritual and tradition and crave community but are unwilling to cede the definition and practice of religion to the Orthodox.

The solemn day of Yom Kippur is, or used to be, the one holiday that most Jews, however, lax or secular in their practice, tend to observe in some fashion. In fact, it has been said, this was one reason it was relatively easy to launch an emergency call-up of Israel's reserves when Arab armies launched their surprise attack in 1973: one knew where to find the troops. Had the attack come on Rosh Hashanah, they would have been dispersed around the country on picnics and other outings. (New revelations about the intelligence and communications failures on the eve of the war came from the archives just this past week.)

Still, as a story in today's Times of Israel notes, even those who mark the holiday in some form or fashion may not do so in traditional ways. Many secular Israelis may attend the opening evening service and then go cycling the next day rather than attend hours of services with which they are not familiar or comfortable. The article describes various organizations that, akin to the Kibbutz Institute, are attempting to craft meaningful forms of engagement with the holiday for the non-observant: including secular study of religious texts, liturgy drawing upon contemporary literature and music, confessional services "focusing on community and nation," and commemorations of the 1973 war.

As author Ben Sales notes, "Yom Kippur lacks an element of national heroism central to such holidays as Chanukah and Purim, which many secular Israelis observe," but "the ideas of self-improvement and forgiveness should resonate with everyone." In other ways, it is therefore easy to integrate the observance of Yom Kippur into modern secular sensibilities and lifestyles. "Green Prophet," an environmental organization that calls itself a "sustainable voice for green news on the Middle East" from all peoples and faiths in the region, offers tips to "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Help Green the World."

Eventually, the standoff in the years after the Yom Kippur War led to the breakthrough that began the long, torturous, and still incomplete "peace process." As the example of Presidents Abbas and Peres reminds us, political leaders as well as individuals often exchange holiday greetings. The excellent new Israel Archives blog of State Archivist Yaakov Lozowick has been releasing a steady stream of new material. Last week, it shared exchanges of New Year greetings between Presidents Carter and Reagan and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Responding to Carter's holiday wishes in 1979, Begin wrote:

In accordance with the ancient calendar the year 5739 had ended and, in ushering in the New Year 5740 we pray that it may, indeed, be blessed. The twelve months gone by will be remembered as the year in which the Camp David agreement was concluded and the treaty of peace between Israel and Egypt was signed. And as you rightly state, Mr. President: 'This new year finds the ties between our two countries stronger than ever.'What a difference three decades make. But on to lighter topics.

Several cultural organizations, including the National Yiddish Book Center on the campus of Hampshire College here in Amherst and the Magnes Museum in Berkeley, have resurrected and updated the old traditions by allowing web visitors to send e-greetings of vintage cards. A few examples from the Magnes:

[source]

[source]

Still, my favorite, which perfectly captures the combination of spiritual and secular, observance and irreverence, has to be this one. As a window into a cultural mindset, it just says it all.

I'm all out, so I'll stop here.

Resources

• Last year's post

• Hemi Amior, "Shana Tova from Alfred Dreyfus," Ynet News, 17 September 2012

• "Rosh Hashana Greeting Cards in Jewish and Israeli Tradition," from National Library of Israel (a fuller range of examples, from which Amior selected his illustrations)

• Matti Friedman, "Bialik and Kipling, but no God: How kibbutz pioneers marked Rosh Hashanah," Times of Israel, 16 Sept. 2012

• Ben Sales, "The un-Orthodox approach to Yom Kippur in Israel," 23 Sept. 2012

• Miriam Kresh, "Make Yom Kippur Your Day to Green the World," Green Prophet, 23 Sept. 2012

• Yaakov Lozowick, "Jewish New Year Greeting Exchanges From Presidents Carter and Reagan and Israeli Prime Minister Begin," Israel's Documented Story, 20 Sept. 2012

• "Rosh Hashanah E-Cards from the Magnes Museum," The New Centrist, 9 Sept. 2009

No comments:

Post a Comment