"In fiction, the principles are given, to find

the facts: in history, the facts are given,

to find the principles; and the writer

who does not explain the phenomena

as well as state them performs

only one half of his office."

Thomas Babington Macaulay,

"History," Edinburgh Review, 1828

Friday, February 27, 2015

When a Minstrel Show in Amherst "was considered a success"

To be precise, "considered a success both in its performance and numbers, as shown by about 350 in attendance."

The date: 1951. A few years before Brown v. Board of Education but well after supposedly decent and educated people should have known better.

Not even 65 years ago, but the distance between that time and this seems much greater.

ICYMI: Read the full story.

And afterwards, be sure to fill out the Amherst Together survey so that we can "advanc[e] community, collaboration, equity and inclusion."

Update (19 March)

Of course, it could be worse:

Belgium minister sparks scorn by 'blacking up' (CNN, 19 March 2015)

Marking Human Rights Day in Amherst

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,...

As I noted in a recent post, the Massachusetts legislature honored the Amherst Human Rights Commission with a special citation on the occasion of our first official Black History Month ceremony last year.

The charge of the Commission is “to ensure that no power goes unchecked, and that all citizens are afforded equal protection under the law,” specifically: "to insure [sic] that no person, public or private, shall be denied any rights guaranteed pursuant to local, state, and/or federal law on the basis of race or color, gender, physical or mental ability, religion, socio-economic status, ethnic or national origin, affectional or sexual preference, lifestyle, or age."

An earlier version of the statement spoke, rather more ambitiously, of "promot[ing] economic and social justice for all citizens through means of mediation, education, and enforcement of local, state, federal, and international human rights laws”--above all, as embodied in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Although the Declaration finds no formal resonance in the official documents, it nonetheless embodies the spirit that moves the Commission. Accordingly, it has become our custom for the Select Board each December to issue a proclamation for the celebration of International Human Rights Day, on the anniversary of the promulgation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. By tradition, the Human Rights Commission then marks the occasion with a candlelight vigil and reading of the Declaration on the Town Common in the evening (often followed by a thematic presentation on a subsequent day).

Members of the Amherst Human Rights Commission and supporters who celebrated the Declaration last December included Department of Human Resources/Rights Director Deborah Radway, Human Rights Commission Chair Gregory Bascom, Bonnie McCracken, Frank Gatti, Eleanor Manire Gatti, and Robert Pam

***

"Many of the assumptions about who wrote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are wrong. The less known story of the men and women who wrote this foundational, emancipatory and anti-colonial document must be told in today's world."

Even those familiar with the Declaration probably do not know the story behind it. Some years back, Gita Sahgal, founder of the Centre for Secular Space, and the former Head of the Gender Unit at Amnesty International, took on this educational challenge.

These are challenging times, she observed. On the one hand, modern philosophers reject the whole concept of demonstrable or natural rights as a throwback to an earlier, naïve age (Alasdair MacIntyre: “tantamount to belief in witches and unicorns”), while on the other, some strains of leftism and postmodernism reduce such supposed “rights” to “the political philosophy of cosmopolitanism” that “‘constitutionalise[s]‘ the normative sources of Empire.” (I’m feeling guilty already.) As Sahgal drily observes, those fighting the Bush administration’s practice of torture and the continued existence of the Guantanamo detention facility “would be surprised to see themselves as empire builders,” while the authors of the Declaration, for their part, would have found "absurd" “The idea that different peoples were endowed with separate rights,” as exemplified by the attempt to create a specific Declaration of Human Rights in Islam.

Citing the work of Susan Waltz, she explains that the origins and character of this fundamental document are both more varied and more radical than even its admirers realize. For example, it is commonly attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt because she chaired the drafting committee, yet she contributed little to the concept or the content. (The idea in fact originated with the President of Panama.) The notion that “western” powers were responsible for the sections on civil and political rights, and the Soviet Union, for those on social and economic ones, is also a gross oversimplification. The desire for emancipation of all, emphasizing that rights applied to everyone everywhere, emerged as a major concern. Significant additions were made by newly de-colonized states regarding, slavery, discrimination, the rights of women, and the right to national self determination.

A host of countries, not least the smaller or emerging ones, saw to it that the document addressed social rights as well as the rights of colonized and other non-self-governing territories. An Indian activist fought for language referring to rights of ”human beings” rather than men, lest it be construed as discriminatory against women. Several Muslim delegates supported the clauses on freedom of religious choice. The final product was truly a collective one

Fifty nations voted in favor of the Declaration. None dared oppose it, but (big surprise), Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and the Soviet Union abstained. Still explains a lot (plus ça change).

* * *

The Amherst Human Rights vigil on the occasion of the document's anniversary is at once a sobering (not to say: depressing) and an inspiring occasion: sobering because, in this town of nearly 38,000 residents--and some 27,000 students--where (as the expression goes) "only the 'h' is silent," I don't believe I have ever seen more than a dozen citizens from among our self-proclaimed liberals, progressives, radicals, and revolutionaries ever put on a down coat and show up. To be sure it's cold and dark, and yet . . . it is an important symbolic commitment to a vital cause. Again, it can be a lot to ask for a symbolic 30-minute gesture on a frigid December night. (I freely admit that I myself am at times the laziest person in the world.) Still, . . . . you get the point.I hope that residents, and above all, my fellow members of Town government--employed, elected, and appointed--will in future consider taking part in what for me is one of the most moving political experiences of the year. When we hold the ceremony, we take turns reading from the Declaration, basically one clause/per person at a time. I have to confess that I often have to suppress a shudder when my turn comes, no matter which paragraph is at issue. The preface is a stirring document:

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, Therefore THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY proclaims THIS UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

How can a chill not run down one's spine when one contrasts the noble goals and innocent hopes of 1948 with--taking all progress into account--the atrocities of the present day?

Scenes from past vigils

2011

On the evening of December 9, one of the first that felt truly cold in what has been a comparatively mild season, a small group gradually assembled under the guidance of tireless Chair Reynolds Winslow.

Everyone received a candle and a copy of the Declaration, in the form of an illustrated “passport,” produced by Amnesty International.

|

| at right: Bonnie McCracken |

As we stood in the cold, many of us attempting to hold both a candle and text in gloved hands, a car with a couple of blonde college-age women in it drove by, and the driver leaned out the window and helpfully shouted, “Hey, what the fuck are you doing?!”

That could have been a metaphor for the problem: ignorance and scorn. We knew exactly what we were doing, yet they had no clue. In a way, it’s understandable: at the end of the college semester, if students venture out into the Friday night cold, it is for physical rather than moral pleasures. And what of the rest of the town? In a community that prides itself on its “activism” and can readily generate a crowd with signs and candles for any “cause,” whether epochal or trivial, it was disappointing to see that we could with difficulty muster only about a dozen participants.

|

| the vigil: Amherst Human Rights/Resources Director Eunice Torres, foreground |

As we began to read from the Declaration, the sirens of police and fire vehicles, far more loudly, yet much less offensively, also interrupted the event.

The intense dedication of its participants stood in inverse proportion to the size of the gathering. The nominal membership of the Commission is nine, though at the moment only six seats are filled: three of them, notably, by high school students. Human Rights Director Eunice Torres was there representing Town staff, and I was present on behalf of the Select Board.

A few interested residents rounded out the group. Some were just supportive. Others, including Commission member Mohammed Ibrahim Elgadi, were from our Sudanese community, and brought with them a deep commitment to human rights arising from their own suffering. Mr. Ibrahim, who was tortured for his activism, is the founder and chair of Group Against Torture in Sudan (GATS). Sudan was in fact the focus of last year's program.

An elderly woman from Egypt, wearing a headscarf and speaking in Arabic through a translator, said that she was proud of the changes that her compatriots had accomplished in the past year, and hoped that their example would bring democratic change to the rest of the Africa in the next one. It seemed a fitting way to close.

On Saturday, December 10, the Commission, as is its custom, made a presentation on human rights work to the community, hosted a potluck luncheon, and distributed posters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This year the presentation was devoted to human rights and relief work in Haiti.

2012

| |

| Deborah Radway (Director, Amherst Dept. of Human Resources/Human Rights), Judy Brooks |

Judy Brooks and Human Rights Commission Chair Reynolds Winslow read from the Preface

2013

As the preceding photos show, holding the vigil on the corner of the Common at the four-way intersection of Town Hall had the advantage of visibility but the disadvantage of an unprepossessing setting and traffic noise that interrupted the reading. Beginning in 2013, the Commission moved the ceremony a few yards to the southeast, beneath the "Merry Maple" tree and closer to Town Hall.

2014

|

| Human Rights Commission Chair Gregory Bascom |

Resources

• The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (from the UN)

• 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (from the UN)

• Gita Sahgai,”Who wrote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?” 50.50 Inclusive Democracy, 9 December 2011

Thursday, February 19, 2015

How I First Learned About the Internment of Japanese Americans

It's hard to recall exactly how I first learned of the "Japanese internment." That is, I know I first learned of it from my parents when I was a schoolchild, but it is the context that escapes me.

On the one hand, my parents told me of Quaker friends in the Twin Cities who had been conscientious objectors and somehow assisted Japanese Americans in that era. On the other hand, my clearest memory is of my parents' conversations with Japanese-American friends in Madison who had been interned, in the Manzanar and Jerome (Arkansas) camps, respectively.

Paul Kusuda, later the Deputy Director of the Bureau of Juvenile Services for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, became one of my father's first colleagues and closest friends when we moved to Madison. Early on, he and his wife Atsuko invited us over to dinner (for some reason, I recall that it was the first time I encountered zucchini). It was a perfect pairing: both husbands worked for State social services, and both wives were librarians--and their son (also named Jim) and I discovered a common interest in hiking, fishing, and the outdoors. In addition, it turned out that Paul and my father had much to share with one another as they compared their experiences of discrimination in the US and Europe during the wartime years.

Especially after retirement, Paul dedicated his time to groups working on behalf of Asian Americans and civil rights, and in particular to the quest for US acknowledgement of the wrongs done by the internment. He served as Chair of the Wisconsin Organization of Asian Americans and at age 92 is still a regular columnist for Asian Wisconzine.

Dedication to the highest ideals of this country

Among the things that impressed me most about Paul were his even temperament, relentlessly calm and thoughtful approach to all aspects of life, and sense of humor (which not only extended to but in fact began with himself). He was the recipient of multiple awards for his activism on behalf of civil rights as well as for his professional work. The citation accompanying his 2006 Dane County Martin Luther King, Jr. Award read:

Still, his quiet anger at the injustice came through at the time and in his recollections. Fighting poverty in a rough Los Angeles neighborhood, he had managed to start taking college courses in engineering. Ironically, he received his acceptance as a naval ordnance inspector for the San Francisco shipyards at the beginning of December 1941. A week later, it was rescinded without explanation, though none was needed. In February came the notorious Executive Order 9066, but he was certain that, as a loyal American, he would not be rounded up. In April, the family was given a week's notice for relocation to Manzanar. The disappointment was harsh.

Why was it that we were . . . singled out . . . ?

As he recalled,

His continuing faith in the American system has not prevented him from criticizing subsequent government policy--from overreactions in the wake of the 9-11 attacks to the invasion of Iraq--for he saw no contradiction in being as concerned for civil liberties as security. As a profile in the Madison Times put it:

Footnote

However I first learned of the internment, I soon read all I could on the subject, which in that day was not a great deal--e.g. America's Concentration Camps, Farewell to Manzanar, and Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps--the topic was not nearly as well known as it is now. To give you a sense of how things have changed: when I was growing up, few children or adults knew about this shameful episode. Today, by contrast, and thankfully, it is so well known that, when I ask students what they first associate with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it is as likely to be the Japanese internment as the New Deal or the US to victory in World War II. An illustration of the mixed blessings of progress, if ever there was one.

A selection of Paul's columns on his life and issues of diversity:

Related posts on this blog:

On the one hand, my parents told me of Quaker friends in the Twin Cities who had been conscientious objectors and somehow assisted Japanese Americans in that era. On the other hand, my clearest memory is of my parents' conversations with Japanese-American friends in Madison who had been interned, in the Manzanar and Jerome (Arkansas) camps, respectively.

Paul Kusuda, later the Deputy Director of the Bureau of Juvenile Services for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, became one of my father's first colleagues and closest friends when we moved to Madison. Early on, he and his wife Atsuko invited us over to dinner (for some reason, I recall that it was the first time I encountered zucchini). It was a perfect pairing: both husbands worked for State social services, and both wives were librarians--and their son (also named Jim) and I discovered a common interest in hiking, fishing, and the outdoors. In addition, it turned out that Paul and my father had much to share with one another as they compared their experiences of discrimination in the US and Europe during the wartime years.

|

| source: Asian Wisconzine. |

Dedication to the highest ideals of this country

Among the things that impressed me most about Paul were his even temperament, relentlessly calm and thoughtful approach to all aspects of life, and sense of humor (which not only extended to but in fact began with himself). He was the recipient of multiple awards for his activism on behalf of civil rights as well as for his professional work. The citation accompanying his 2006 Dane County Martin Luther King, Jr. Award read:

Mr. Kusuda was in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II. Instead of allowing that unfortunate and painful experience to make him bitter, Paul Kusuda has worked hard to heal those wounds by working very hard with the Japanese American Citizens League of Wisconsin and other organizations - - a labor of strength, dedication to the highest ideals of this country, and forgiveness that is consistent with Martin Luther King’s insistence that we must not succumb to the poison of hate.His utter refusal to become bitter is indeed one of the hallmarks of his character. During his internment and afterward, he was never one of the radicals. As he later explained, as a loyal citizen and believer in the rule of law, he saw it as his duty not to resist the internment order, but to challenge it through peaceful remonstrance and questioning.

Still, his quiet anger at the injustice came through at the time and in his recollections. Fighting poverty in a rough Los Angeles neighborhood, he had managed to start taking college courses in engineering. Ironically, he received his acceptance as a naval ordnance inspector for the San Francisco shipyards at the beginning of December 1941. A week later, it was rescinded without explanation, though none was needed. In February came the notorious Executive Order 9066, but he was certain that, as a loyal American, he would not be rounded up. In April, the family was given a week's notice for relocation to Manzanar. The disappointment was harsh.

Why was it that we were . . . singled out . . . ?

As he recalled,

We were at war with Germany, Italy, and Japan (Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941). Yet, only persons of Japanese ancestry were uprooted as a group and forcibly evacuated from the west coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington. Of the approximately 120,000 persons involved, two-thirds were American citizens, euphemistically called non-aliens. Only persons of Japanese ancestry were summarily, without trial or allegation, removed from the West Coast. Persons of German or Italian ancestry were individually identified, and if determined to be of possible danger to our country, sent to internment camps.His typed and handwritten letters (many on file in the Japanese American National Museum) reflect his growing disillusionment. In May 1942, he wrote to his teacher and supporter, Mrs. Afton Dill Nance:

My morale isn’t really low. From now on, I’m not going to trust anyone when it comes to governmental affairs. To think that I got faily [sic] good grades in civics, American History, Political Science, etc., makes me laugh because Ireall [sic] believed in all that I studied. Maybe this darn bitterness will work off – I hope so. Anyway, I’m waiting for something so that I can again cling to to all that America means to me. I guess that at the present time, I’m in the throes of meloncholia [sic] or something. Perhaps that may be changed. Ihope [sic] that it will change for the better soon.

Here is something to think about --- it made me think for quite a bit. A sentry shot a kid of about 17 or 18 for crossing a line when the former soldier on watch gave the youngster permission to cross the sentry line. What kind of a deal is it when even kids are shot for such a minor infraction of rules. Darn it all, I’m really disgusted with it all.

And a week later:Hasta la vista,Paul H.

Time and time again, I have argued that America is not a democracy for white people only. Was I wrong? God help us all if I am or was because what a future is in store for everyone in a false democracy!Angered that the draft classifications of all Japanese Americans had been changed from 1-A to 4-C, he also wrote to President Roosevelt, asking why the Japanese Americans were singled out as untrustworthy, and insisting on the right to be allowed to fight:

Dear Mr. President:Paul Kusuda was lucky in that he spent only a year in the camp. At the beginning of 1943, the government changed its policy and decided to recruit Japanese Americans for the war effort. He was unsuccessful in enlisting, but he was allowed to go to Chicago to study social work, which he had in the meantime chosen over engineering as his future profession. (How he doggedly tried to get into the Army before and after moving to Chicago makes for both sad and humorous reading.)

As you know, persons of Japanese parentage have been

evacuated from the western coastal regions of the United States.

Many of us do not know exactly why we were sent out of those

areas, although numerous attempts have been made to justify such

action. However, we are anxious to comply with all the govern-

mental regulations which may be established.

The greater majority of the Japanese people in the

United States are whole-heartedly for ultimate victory of the

Allied Nations, and yet, we are referred to as "Japs." That term

used in scorn is very hateful to us; many of us deem it an insult.

Not many people think enough to call us Americans.

In schools, everyone is taught that in the eyes of the

law, all persons are considered innocent until proven to be guilty.

But, why was it that we were branded as potential spies we were

singled out as threatening democracy, we were and are considered

dangerous? That hurt! What cases of sabotage promoted by us can

be said to justify the up-rooting of our hard-earned way of living?

What can justify the fact that we Americans are not allowed to aid

in the war effort? What can justify the fact that many students

are cut off from education without reason? Is that at all fair?

Try as we may, the reasons cannot be found to answer such questions.

Now, it is too late to undo the harm created by the forced

evacuation, but we want you to realize that we are not saboteurs, we

are not axis [sic] agents, we are not "Japs." But, we are Americans.

Give us a real chance to prove ourselves.

Sincerely yours,

Paual H. Kusuda

B 19-9-2

Manzanar Reception Center

Manzanar, California

His continuing faith in the American system has not prevented him from criticizing subsequent government policy--from overreactions in the wake of the 9-11 attacks to the invasion of Iraq--for he saw no contradiction in being as concerned for civil liberties as security. As a profile in the Madison Times put it:

Paul Kusuda is a law-abiding, Made in the USA, U.S. citizen. And Kusuda, a long-time Madison activist and retiree from the WI Division of Corrections, has some grave concerns about parts of the USA Patriot Act. He wonders about the two U.S. citizens who are currently being detained indefinitely at Guantanamo Bay without access to a lawyer or the courts. Theoretically speaking, they could be incarcerated there for the rest of their lives without ever having been charged with or convicted of a crime.

Kusuda wonders and is concerned because he's been there before. Kusuda is one of 120,000 Japanese Americans who were detained during World War II in relocation camps on the desert fringe in California without due process or having been accused of a crime. Kusuda knows how it feels.

Footnote

However I first learned of the internment, I soon read all I could on the subject, which in that day was not a great deal--e.g. America's Concentration Camps, Farewell to Manzanar, and Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps--the topic was not nearly as well known as it is now. To give you a sense of how things have changed: when I was growing up, few children or adults knew about this shameful episode. Today, by contrast, and thankfully, it is so well known that, when I ask students what they first associate with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it is as likely to be the Japanese internment as the New Deal or the US to victory in World War II. An illustration of the mixed blessings of progress, if ever there was one.

A selection of Paul's columns on his life and issues of diversity:

- "Are memories to keep or to tell?" recalls how my parents encouraged him to tell his story and others eventually persuaded him to share it with NPR's StoryCorps

- "An Interview with Paul Kusuda: We Have Been Down This Road Before": from his parents' immigration to the internment order;

- "Day of Remembrance" (2008)

- "Day to Remember for Many Nisei" (2011) (Part 1; Part 2)

- "Relocation Center to Chicago" (Part 1; Part 2; Part 3

- "Close Friends Grow Fewer": includes a tribute to Akira Toki, member of Madison's only Japanese American family prior to Pearl Harbor. Toki went on to serve as a decorated member of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, made up of Nisei. In the 1990s, Madison named a middle school in his honor.

- "Congressional Gold Medal awarded to long-time Madisonian": one of the Japanese-American veterans honored in 2011 for his service in World War II. He went from Minidoka to military intelligence (his brothers served in the the 442nd Regimental Combat Team) to studies at MIT (under Mies van der Rohe) and an architectural practice in Madison. (I went to high school with his daughters)

- "Patriotism is Not Just a Word": from Manzanar to the present, believing in the American system, opposing the war in Iraq (Part 1; Part 2)

- "Are racial minority groups truly accepted in the Midwest?": includes first encounters with African Americans, and how residents of Madison protected the only Japanese-American family (Part 1; Part 2)

* * *

Related posts on this blog:

- Historic Preservation and the Memory of Injustice (2008)

- 19 February: Japanese American Day of Remembrance (2009)

- National Park Service Commits Circa Four Million Dollars to Japanese-American Internment Sites (2011)

- Japanese American Day of Remembrance. A Booklet Shows the Face of Hatred (2015)

- Contemplating Cruelty: An Infamous Life Magazine Photo from 1944 (2015)

Contemplating Cruelty: An Infamous Life Magazine Photo from 1944

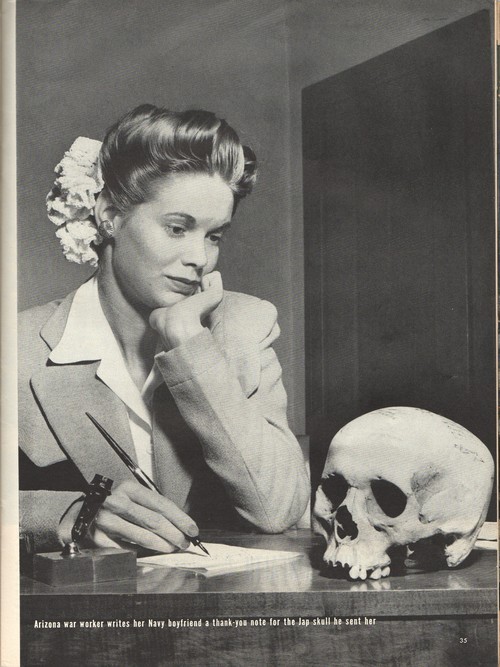

This photograph of an Arizona war worker posing with the skull of a Japanese soldier that her Navy boyfriend had sent her appeared in Life (the preeminent photojournalism magazine) in 1944 and soon became famous. (I was recently fortunate enough to acquire a copy of the issue for my collection.)

It reflects the vicious hatred that US and Japanese combatants brought to their struggle after Pearl Harbor. Although the US military condemned the practice of collecting human trophies, Life noted this in passing, treating the incident as a sort of human interest story.

We like to think that we have advanced beyond this stage. Certainly no coverage of a comparable incident on the part of US troops would pass with such understated commentary. (Meanwhile, ISIS decapitates and incinerates.)

Read the full story on the tumblr.

Related posts:

It reflects the vicious hatred that US and Japanese combatants brought to their struggle after Pearl Harbor. Although the US military condemned the practice of collecting human trophies, Life noted this in passing, treating the incident as a sort of human interest story.

We like to think that we have advanced beyond this stage. Certainly no coverage of a comparable incident on the part of US troops would pass with such understated commentary. (Meanwhile, ISIS decapitates and incinerates.)

Read the full story on the tumblr.

Related posts:

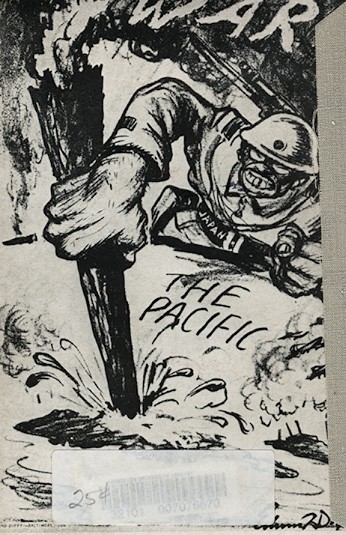

Japanese American Day of Remembrance. A Booklet Shows the Face of Hatred

Today, though too few of us know it, is the National Japanese American Day of Remembrance, marking the anniversary of the promulgation of Executive Order 9066. As the National Archives explains:

Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the evacuation of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to relocation centers further inland. In the next 6 months, over 100,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were moved to assembly centers. They were then evacuated to and confined in isolated, fenced, and guarded relocation centers, known as internment camps.The illustration below, from a booklet in my collection, illustrates as well as anything else the attitudes that shaped the decision to relocate Japanese-Americans as well as "enemy aliens."

Read the full story on the tumblr.

Related posts:

- Historic Preservation and the Memory of Injustice (2008)

- 19 February: Japanese American Day of Remembrance (2009)

- National Park Service Commits Circa Four Million Dollars to Japanese-American Internment Sites (2011)

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Scenes From the First Official Amherst Black History Month Celebration, 2014

The weather on the occasion of the first official Black History Month celebration in Amherst last year could not have been more different from what we experienced this past weekend. In 2014, some of the roughly two dozen participants wore short sleeves as they listened to UMass student and Amherst Human Rights Commissioner Damon Mallory open the ceremony.

State Representative Ellen Story and State Senator Stan Rosenberg presented the Town with two documents from Boston. The first of these was a citation from the Legislature, honoring the founding of the Amherst Human Rights Commission.

Front row, left to right: NAACP member and former Select Board member Judy Brooks, Human Rights Commissioners Sid Ferrierra, Damon Mallory, Kathleen Anderson (also NAACP President), and Gregory Bascomb.

The second document was a proclamation by Governor Deval Patrick in honor of Black History Month.

Another project of Black History Month in Amherst consisted of posters in local store windows, celebrating African American figures with a connection to the town. Two examples:

Springfield-area Civil War reenactors of the Stone Soul Soldiers, Peter Brace Brigade, provide an honor guard for the ceremony.

State Representative Ellen Story and State Senator Stan Rosenberg presented the Town with two documents from Boston. The first of these was a citation from the Legislature, honoring the founding of the Amherst Human Rights Commission.

Back row, left to right: Civil War reenactor Charleston Morris, State Rep. Ellen Story, State Sen. Stan Rosenberg

The second document was a proclamation by Governor Deval Patrick in honor of Black History Month.

Proclamation By His Excellency Governor Deval L. Patrick

Whereas During the month of February people gather together across the country to celebrate Black History Month and

Whereas Black History Month reminds us of the struggles and personal sacrifices of African Americans, and honors their outstanding contributions and achievements, especially in the advancement of civil rights and equality; and

Whereas Massachusetts African Americans have made a great imprint upon our country's landscape: Edward Brooke, the first Black Senator elected by popular vote; Crispus Attucks, the first causality of the American Revolution; W.E.B Du Bois, author, historian and civil rights activist; and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first official black regiments of the Civil War; and

Whereas Our vibrant African American community continues to be a vital part of the Commonwealth's rich diversity by contributing significantly to all aspects of daily life, including education, medicine, commerce, agriculture, communications, public service and high technology,

Now therefore, I, Deval L. Patrick, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, do hereby proclaim February 2014, to be,

BLACK HISTORY MONTHAnd urge all the citizens of the Commonwealth to take cognizance of this eventand participate fittingly in its observance.Given at the Executive Chamber in Boston, this twelfth day of February, in the year two thousand and fourteen, and the Independence of the United States of America, the two hundred and thirty-seventh.By His Excellency Deval L. Patrick

Another project of Black History Month in Amherst consisted of posters in local store windows, celebrating African American figures with a connection to the town. Two examples:

Singer-songwriter Natalie Cole studied at the University of Massachusetts.

Prolific author and former UMass professor Julius Lester. On April 16, he

will receive the 2015 Award for Local Literary Achievement

Springfield-area Civil War reenactors of the Stone Soul Soldiers, Peter Brace Brigade, provide an honor guard for the ceremony.

Second Annual Amherst Black History Month Celebration, New Select Board Proclamation

For the second year in a row, the Town of Amherst, responding to the initiative of residents, has celebrated Black History Month with a ceremony in front of Town Hall.

Over three dozen participants--an impressive figure given that the thermometer stood at a bitter 8 degrees Fahrenheit (-13 C) with a wind chill of around -1--braved the cold to signal their commitment to Black history and human rights.

Community activist and former Select Board member Judy Brooks in both years played a crucial role in making this event happen. My fellow Select Board member Alisa Brewer (@avbrewer) took the initiative in coordinating the Town involvement and working out the details of our 2015 ceremony.

This year, likewise in response to requests from the community, the Town for the first time issued an official proclamation marking the occasion and calling upon all residents to join in celebration. It made perfect sense: after all, we annually issue a proclamation for Puerto Rican Day and Tibet Day, and just two weeks ago, we marked the first Irish Day. It was but logical that we formally acknowledge an event that has been celebrated around the country for decades.

From Negro History Week to Black History Month

Many of us are familiar in general terms with "Black History Month," but not with its origins. In 1926, historian and journalist Carter G. Woodson initiated Negro History Week as a means of calling attention to the struggles and success of African Americans. He chose the second week of February because it included the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass fell. Within a few years, most states acknowledged the event. In 1969, in the context of the political upheavals of the Civil Rights and peace movements, members of the Black United Students at Kent State University urged the expansion of the celebration to a full month, which took place the following year, (only months before the University gained notoriety as the site of the notorious killing of antiwar protesters). In 1976, President Gerald Ford lent the authority of the federal government to the new month-long celebration, which entered into public law with the Congressional Resolution of February 11, 1986. Since 1978, the United States Postal Service has issued commemorative stamps for Black History Month. Although referred to as "National African American History Month" in more recent US proclamations, "Black History Month" remains the more common popular term.

Amherst Black History Month Proclamation, 2015

Let our rejoicing rise / High as the listening skies

In 2015 as in 2014, a central feature was the raising of the African American flag, and the singing of "Life Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the "Black National Anthem."

We were sorry that the press did not show up to cover the event, but all the more grateful that reporter Scott Merzbach (@scottmerzbach) managed to rush out an advance story on Black History Month in the Gazette, which probably did a great deal to boost turnout. We hope that next year the Human Resources/Human Rights Department in Town Hall will take charge of the event to emphasize its status as a Town-sponsored and regular observance.

Note: because I was participating in the ceremony, I could not take as many photos as I wished, but Larry Kelley offers a selection on his blog. Unfortunately, his post generated some ugly comments. I am appalled at (by not surprised by) the venom and racism. It is a real shame: he tried to report objectively on a town event, and the talkbacks are dominated by hate speech (and rebuttals).

Amherst Proclamation on Black History Month: the names

I was tasked with crafting the document for the Town. One course of action that was suggested--and it would have been the easiest--would have been simply to duplicate either the current presidential or recent Massachusetts gubernatorial proclamations. However, the former dealt with both more general and more contemporary matters, and the latter seemed, frankly, rather perfunctory as regards Massachusetts history, as well as lacking the eloquence of the former.

Some topics or individuals appear virtually de rigueur, but at the same time, one hopes not simply to reinforce the commonplace. For example, it seemed obligatory to mention the soldiers of the famed Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry--but, although they are among my personal historical favorites, the single-minded focus on this one regiment (an emphasis reinforced by the popularity of the Hollywood portrayal in "Glory") can tend to shortchange the Black soldiers who fought in other units: Of the 21 Amherst African Americans who bore arms for the Union, only 7 served in the 54th. Only 5 of the 21 identified by name are buried in West Cemetery, and only one of those is from the 54th. Our text therefore notes that the 54th was the first and most famous of these heroic units.

The 2014 Massachusetts proclamation listed only male politicians and military men, so I made sure to include figures from other fields--and women.

For example, many believe that the first Black US college graduate was from Oberlin--presumably because of the school's association with abolitionism--but the earliest Black college graduates were in fact all from New England: the first from Middlebury, in 1823; and the second, Edward Jones, from Amherst (1826). It seemed important to call attention to our local history, and to remind the public that innovation and inclusiveness at Amherst College have a long tradition. The inclusion of Jan Matzeliger, the self-taught inventor who solved the last and most difficult problem in the mechanization of the shoe trade, calls attention both to Black immigrants (he was from Dutch Guiana) and to the neglected but important role of African Americans in technology and industry. As Mass Moments explains, his invention made it "possible for working people to afford decent shoes" and "Today, all shoes manufactured by machine — more than 99% of the shoes in the world — use machines built on Matzeliger's model."

In the case of women in African American history, we often think of the political activists, such as famed abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who lived in nearby Florence. I chose to focus on the contributions to high culture: the eighteenth-century poet Phillis Wheatley is of course known to scholars of American history and literature but is not exactly a household name. Even less well known is Edmonia Lewis, the first professional African American sculptor. It was in Boston in the 1860s that she studied art and exhibited two sculptures of heroes of the Massachusetts 54th. Proceeds from sales of copies of her bust of Col. Shaw both supported Black soldiers and funded her relocation to Rome, where she won international acclaim.

Any short list is necessarily incomplete and subjective, but future proclamations can include further individuals and groups. One hopes that the proclamations and lists will provide an opportunity to educate our community about the African American contributions to our collective society and heritage. (See also the resources for further reading at the bottom of this page.)

A footnote:

After the ceremony, retired Amherst College physics professor and amateur historian Bob Romer buttonholed me to "quibble" with one aspect of the proclamation: The "abolition" of slavery, he said, hadn't actually eliminated the practice in Massachusetts. His research taught him that here, as elsewhere in New England, "slaves" continued to appear in lists of property and the like for some time afterward. That is true, but it's also irrelevant, and in two ways.

First, although this fact may come as a revelation to some, it is not news to professional historians. As the Massachusetts Historical Society explains, "slavery did not disappear completely for some time. Slavery, often recast as indentured servitude . . . was not unheard of in Massachusetts through the end of the eighteenth century."

Second, be that as it may, it in no wise diminishes the significance of the action, and to harp on it is therefore to misunderstand the nature of both historical action and contemporary commemoration.

The Massachusetts Constitution stated:

The Massachusetts Historical Society concludes, "Together with the Mumbet decision, the Quock Walker trials effectively ended slavery as a legal practice in Massachusetts." It therefore calls the 1783 decision a "monumental ruling."

One could make a comparable point about the Emancipation Proclamation, whose anniversary we recently celebrated. It applied only to the territories of the Confederacy not yet under the control of the Union. Secretary of State William Seward observed with bitter but exquisite irony: "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Nonetheless, as the National Archives says, "Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free a single slave, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of African Americans, and fundamentally transformed the character of the war from a war for the Union into a war for freedom."

We can acknowledge the limitations of these two abolition measures and nonetheless hail them as landmarks.

Q.E.D.

Coming attractions:

Because I didn't manage to write at the time of last year's ceremony, I will now post some photos from that event.

Resources

The History of Black History Month

Historic Sites

Further reading on some of the figures and events mentioned in our proclamation:

Phillis Wheatley

Black History Month word cloud logo on Town website,

designed by our skilled GIS guy and all-'round IT expert Mike Olkin (@MikeOlkin)

Over three dozen participants--an impressive figure given that the thermometer stood at a bitter 8 degrees Fahrenheit (-13 C) with a wind chill of around -1--braved the cold to signal their commitment to Black history and human rights.

Community activist and former Select Board member Judy Brooks in both years played a crucial role in making this event happen. My fellow Select Board member Alisa Brewer (@avbrewer) took the initiative in coordinating the Town involvement and working out the details of our 2015 ceremony.

This year, likewise in response to requests from the community, the Town for the first time issued an official proclamation marking the occasion and calling upon all residents to join in celebration. It made perfect sense: after all, we annually issue a proclamation for Puerto Rican Day and Tibet Day, and just two weeks ago, we marked the first Irish Day. It was but logical that we formally acknowledge an event that has been celebrated around the country for decades.

From Negro History Week to Black History Month

Many of us are familiar in general terms with "Black History Month," but not with its origins. In 1926, historian and journalist Carter G. Woodson initiated Negro History Week as a means of calling attention to the struggles and success of African Americans. He chose the second week of February because it included the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass fell. Within a few years, most states acknowledged the event. In 1969, in the context of the political upheavals of the Civil Rights and peace movements, members of the Black United Students at Kent State University urged the expansion of the celebration to a full month, which took place the following year, (only months before the University gained notoriety as the site of the notorious killing of antiwar protesters). In 1976, President Gerald Ford lent the authority of the federal government to the new month-long celebration, which entered into public law with the Congressional Resolution of February 11, 1986. Since 1978, the United States Postal Service has issued commemorative stamps for Black History Month. Although referred to as "National African American History Month" in more recent US proclamations, "Black History Month" remains the more common popular term.

Amherst Black History Month Proclamation, 2015

Whereas, since the Bicentennial year of 1976, Americans of all walks of life have come together during the month of February “to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history,”

Whereas these accomplishments are the more remarkable for having been won at the cost of great struggle and sacrifice by men and women who came to these shores in chains, and by their descendants,

Whereas the authors of these accomplishments in Massachusetts history include:

Whereas captive Africans and free people of color were already part of the Amherst story in the Colonial era,

- Phillis Wheatley, the first African American to publish a book of poetry in America;

- Crispus Attucks, the first causality of the American Revolution;

- Edward Jones of Amherst College, the second African American to earn a college degree;

- Edmonia Lewis, the first professional African American sculptor, who learned her craft in Boston;

- the members of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first and most famous unit of African American Union soldiers raised in the Civil War

- Jan Matzeliger, inventor who revolutionized the shoe manufacturing industry;

- W. E. B Du Bois, pioneering scholar and civil rights activist;

- Edward Brooke, the first African American senator elected by popular vote;

- Deval Patrick, the second elected African American governor in the nation

Whereas the African American residents of Amherst have fought for our collective defense and freedom from the Revolution and Civil War to the present,

Whereas the African American community—some of whose distinguished figures are depicted on the History Mural in West Cemetery—continues to contribute to the rich diversity and general welfare of both the Town of Amherst and the Commonwealth,

Whereas, to its shame, Massachusetts participated in the slave trade since 1638, but to its honor, in 1783 became the first state in the new nation to abolish slavery as “inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution," thereby demonstrating our determination to live up to our historical ideals as we strive to build a better common future,

Whereas, as President Barack Obama has proclaimed, “Every American can draw strength from the story of hard-won progress, which not only defines the African-American experience, but also lies at the heart of our Nation as a whole,”

Now, therefore, we the Select Board of the Town of Amherst, do hereby proclaim February 2015 as Black History Month, and urge all residents to mark this occasion, and to participate fittingly in its observance, beginning with a flag-raising ceremony to be held in front of Town Hall on February 14.

Voted this 10th day of February, 2015

Amherst Select Board

Aaron Hayden, Chair

Andy Steinberg

James Wald

Alisa Brewer

Constance Kruger

Let our rejoicing rise / High as the listening skies

In 2015 as in 2014, a central feature was the raising of the African American flag, and the singing of "Life Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the "Black National Anthem."

A member of the Massachusetts 54th reeenactors from the Springfield area

salutes the flag. What further commentary could be needed?

We were sorry that the press did not show up to cover the event, but all the more grateful that reporter Scott Merzbach (@scottmerzbach) managed to rush out an advance story on Black History Month in the Gazette, which probably did a great deal to boost turnout. We hope that next year the Human Resources/Human Rights Department in Town Hall will take charge of the event to emphasize its status as a Town-sponsored and regular observance.

Note: because I was participating in the ceremony, I could not take as many photos as I wished, but Larry Kelley offers a selection on his blog. Unfortunately, his post generated some ugly comments. I am appalled at (by not surprised by) the venom and racism. It is a real shame: he tried to report objectively on a town event, and the talkbacks are dominated by hate speech (and rebuttals).

* * *

Amherst Proclamation on Black History Month: the names

I was tasked with crafting the document for the Town. One course of action that was suggested--and it would have been the easiest--would have been simply to duplicate either the current presidential or recent Massachusetts gubernatorial proclamations. However, the former dealt with both more general and more contemporary matters, and the latter seemed, frankly, rather perfunctory as regards Massachusetts history, as well as lacking the eloquence of the former.

Some topics or individuals appear virtually de rigueur, but at the same time, one hopes not simply to reinforce the commonplace. For example, it seemed obligatory to mention the soldiers of the famed Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry--but, although they are among my personal historical favorites, the single-minded focus on this one regiment (an emphasis reinforced by the popularity of the Hollywood portrayal in "Glory") can tend to shortchange the Black soldiers who fought in other units: Of the 21 Amherst African Americans who bore arms for the Union, only 7 served in the 54th. Only 5 of the 21 identified by name are buried in West Cemetery, and only one of those is from the 54th. Our text therefore notes that the 54th was the first and most famous of these heroic units.

The 2014 Massachusetts proclamation listed only male politicians and military men, so I made sure to include figures from other fields--and women.

For example, many believe that the first Black US college graduate was from Oberlin--presumably because of the school's association with abolitionism--but the earliest Black college graduates were in fact all from New England: the first from Middlebury, in 1823; and the second, Edward Jones, from Amherst (1826). It seemed important to call attention to our local history, and to remind the public that innovation and inclusiveness at Amherst College have a long tradition. The inclusion of Jan Matzeliger, the self-taught inventor who solved the last and most difficult problem in the mechanization of the shoe trade, calls attention both to Black immigrants (he was from Dutch Guiana) and to the neglected but important role of African Americans in technology and industry. As Mass Moments explains, his invention made it "possible for working people to afford decent shoes" and "Today, all shoes manufactured by machine — more than 99% of the shoes in the world — use machines built on Matzeliger's model."

In the case of women in African American history, we often think of the political activists, such as famed abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who lived in nearby Florence. I chose to focus on the contributions to high culture: the eighteenth-century poet Phillis Wheatley is of course known to scholars of American history and literature but is not exactly a household name. Even less well known is Edmonia Lewis, the first professional African American sculptor. It was in Boston in the 1860s that she studied art and exhibited two sculptures of heroes of the Massachusetts 54th. Proceeds from sales of copies of her bust of Col. Shaw both supported Black soldiers and funded her relocation to Rome, where she won international acclaim.

Any short list is necessarily incomplete and subjective, but future proclamations can include further individuals and groups. One hopes that the proclamations and lists will provide an opportunity to educate our community about the African American contributions to our collective society and heritage. (See also the resources for further reading at the bottom of this page.)

A footnote:

After the ceremony, retired Amherst College physics professor and amateur historian Bob Romer buttonholed me to "quibble" with one aspect of the proclamation: The "abolition" of slavery, he said, hadn't actually eliminated the practice in Massachusetts. His research taught him that here, as elsewhere in New England, "slaves" continued to appear in lists of property and the like for some time afterward. That is true, but it's also irrelevant, and in two ways.

First, although this fact may come as a revelation to some, it is not news to professional historians. As the Massachusetts Historical Society explains, "slavery did not disappear completely for some time. Slavery, often recast as indentured servitude . . . was not unheard of in Massachusetts through the end of the eighteenth century."

Second, be that as it may, it in no wise diminishes the significance of the action, and to harp on it is therefore to misunderstand the nature of both historical action and contemporary commemoration.

The Massachusetts Constitution stated:

All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.Two legal cases in the 1780s used this text to argue that slavery was illegal in the Commonwealth, and the Chief Justice agreed, writing, "there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational Creature ..."

The Massachusetts Historical Society concludes, "Together with the Mumbet decision, the Quock Walker trials effectively ended slavery as a legal practice in Massachusetts." It therefore calls the 1783 decision a "monumental ruling."

One could make a comparable point about the Emancipation Proclamation, whose anniversary we recently celebrated. It applied only to the territories of the Confederacy not yet under the control of the Union. Secretary of State William Seward observed with bitter but exquisite irony: "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Nonetheless, as the National Archives says, "Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free a single slave, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of African Americans, and fundamentally transformed the character of the war from a war for the Union into a war for freedom."

We can acknowledge the limitations of these two abolition measures and nonetheless hail them as landmarks.

Q.E.D.

Coming attractions:

Because I didn't manage to write at the time of last year's ceremony, I will now post some photos from that event.

Resources

The History of Black History Month

- President Gerald Ford's 1976 federal proclamation of Black History Month

- Barack Obama, Presidential Proclamation -- National African American History Month, 2014

- Barack Obama, Presidential Proclamation -- National African American History Month, 2015

- Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan (in Exile), "Love in the Stacks: Some Thoughts on Black History Month"

- Eric Krupke, "A new generation of voices takes back Black History Month," PBS NewsHour, February 13, 2015

Historic Sites

- Events and sites: Black History Month 2015 in Massachusetts

- Museum of African American History, Boston and Nantucket

- Black Heritage Trail (from Museum of African American History)

- African American Historic Sites of Deerfield, Massachusetts Map & Guide (Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association)

- W. E. B. Du Bois National Historic Site, Great Barrington

Further reading on some of the figures and events mentioned in our proclamation:

Phillis Wheatley

- John Wheatley Purchases a Slave Child, July 11, 1761, (Mass Moments)

- Phillis Wheatley – Boston’s Remarkable Slave Poet of 1772 (New England Historical Society)

- Peter Armenti, Phillis Wheatley (From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress)

- Tracy Potter, review of Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (The Beehive: Official Blog of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

- Christopher Cameron, Phillis Wheatley and the Black Prophetic Tradition (US Intellectual History Blog, 14 June 2014)

- Freedom Rising: Reading, Writing, Publishing Black Books (exhibit at Museum of African American History, Boston, Jan.-Dec. 2015a)

- First Slaves Arrive in Massachusetts, February 26, 1638 (Mass Moments)

- Robert Romer, Slavery in the Connecticut Valley

- African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts (comprehensive online exhibit from Massachusetts Historical Society)

- Jury Decides in Favor of "Mum Bett" Freeman, August 22, 1781 (Mass Moments)

- A History of Amherst College

- Edward Jones (Dictionary of African Christian Biography)

- Edward Jones (missionary) (Wikipedia)

- The Edward Jones Prize from Amherst College for "an honors thesis that addresses a present or future issue of concern to black people in Africa and the Diaspora"

- 54th Massachusetts Volunteers March Through Boston, May 28, 1863 (Mass Moments)

- Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment (Boston African American National Historic Site)

- Tell It with Pride (Massachusetts Historical Society exhibition, 2014)

- Written in Glory: Letters from the Soldiers and Officers of the 54th Massachusetts

- Exhibit: Mass 54th Casualty List (National Archives)

- Andrea Shea, Civil War's First African-American Infantry Remembered In Bronze (NPR, July 18, 2013)

- Massachusetts Civil War regiment to march in inaugural parade (masslive.com, Jan. 12, 2009)

- John Nieb, Springfield Armory program to focus on 54th Massachusetts Regiment (masslive.com, Feb. 10, 2014)

- Stone Soul soldiers (reports on Springfield area African American Civil War reenactors from masslive.com)

- Posts on the Mass 54th from this blog

- excerpt from Harry Henderson and Albert Henderson, The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis

- Sculptor Edmonia Lewis Displays Work in Boston, November 11, 1864 (Mass Moments)

- Stephen May, The Object at Hand (Smithsonian Magazine, Sept. 1996)

- Edmonia Lewis (online exhibition from the Smithsonian)

- Exploring Freedom: Edmonia Lewis (PBS)

- Edmonia Lewis, An Artist With African and Native American Roots (the African American Registry)

- Matzeliger Demonstrates Revolutionary Machine, May 29, 1885 (Mass Moments)

- Jan Matzeliger (blackinventor.com via Harvard)

- Famous Black Inventors (about.com)

- Jan Matzeliger commemorative stamp (from Arago, Smithsonian Institution)

- W. E. B. Du Bois National Historic Site, Great Barrington

- W. E. B. Du Bois Center, University of Massachusetts-Amherst

- W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, University of Massachusetts-Amherst

- W. E. B. Du Bois Online Resources (Library of Congress)

- Senator Edward Brooke born October 26, 1919 (Mass Moments)

- Mark Feeney, Edward W. Brooke, who broke down barriers, dies at 95 (Boston Globe, Jan. 4, 2015)

- Edward Brooke, first black elected senator, dies at 95 (AP; Politico, Jan. 3, 2015)

- Megan R. Wilson, Edward Brooke, first African American elected to Senate, dies at 95 (The Hill, Jan. 3, 2015)

- Scott Neuman, Former Republican Sen. Edward Brooke Dies At 95 (NPR, Jan. 3, 2015)

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Amherst Irish Association Launches Series of Events

On February 1, the new Amherst Irish Association held its inaugural event featuring a talk by Boston Globe reporter (and UMass alumnus) Kevin Cullen (@GlobeCullen) on "Irish Matters: A Journalist's Journey" at the Amherst Unitarian Universalist Society.

Association co-founder íde B. O'Carroll, speaking in both English and Gaelic, introduced Mr. Cullen, whose credentials include covering the conflict in Northern Ireland for over two decades, Pullitzer-prize-winning reporting of the sex abuse scandals in the Catholic Church, numerous stories and a best-selling book on the hunt for mobster Whitey Bulger, and, most recently, award-winning coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing and trial of the accused perpetrator Dzokhar Tsarnaev.

Mr. Cullen began by reading the Select Board's proclamation of the first annual Irish Day.

The time was roughly divided between the formal talk and a free-ranging discussion with the audience.

Topics that came up in the latter included the changes that Mr. Cullen had seen in Ireland over the years, from the performance of the Irish economy to Sinn Féin's electoral prospects in the south, and closer to home, the Bulger and Tsarnaev trials.

In the context of the latter, Mr. Cullen praised Twitter as a journalist's tool. Although, he quipped, his steady stream of coverage lost him some followers--"People say, 'I don't want 300 tweets a day about some guy picking his nose in the jury box'"--he found it an invaluable way to cover events first as they happen and then in more systematic and distilled fashion afterward. Because it was impossible to provide real-time coverage and take detailed notes at the same time, Twitter in effect became his notebook, for he went back to his Twitter stream and used the tweets as the skeleton for his subsequent full-fledged articles.

Even death is an occasion for a good joke

Known for his dry wit and ironic view of the world as well as his reporting, Mr. Cullen immediately earned a laugh from the audience with a joke about Unitarians. Noting that he was taking a risk by being somewhat mischievous given the setting, he suggested that it was a trait he had inherited from this father. He recalled how, as a Boston Irish Catholic, he first learned about Unitarians. His father took him to the funeral of a fireman acquaintance, who happened to be Unitarian. The boy asked what Unitarians were. The father explained and then said: "You know what you call a Unitarian in a casket? All dressed up and no place to go." During the Q & A, Mr. Cullen managed to find humor in another topic involving mortality. Asked whether he had ever feared for his life while covering the pursuit and trial of notorious mobster and murderer Whitey Bulger, he shrugged, "What's he gonna do--throw a box of Depends at me? He's, like, 84 years old."

Irish-American pols old and new get the job done

The bulk of the formal talk, derived from a Globe piece last fall, was devoted to reflections on the changing profile of the Irish-American politician, from quintessential old-time Boston machine politico James Michael Curley to contemporary figures such as newly elected Boston Mayor Martin Walsh and former Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley (often spoken of as a potential Democratic presidential candidate). There were good reasons and historical circumstances, he said, behind the stereotype of the Irish machine politician.

As Cullen observed, the Irish, having faced vicious discrimination, saw the solution in electing their own. Being a good politician meant providing patronage: getting things done for constituents. At times, this approach collided with the ethics of the system or at least the groups that dominated it.

The clash of cultures was epitomized by the incident in which Mayor Curley impersonated an immigrant in order to take his civil service examination for him. As Cullen explained, "The Brahmins were horrified; the Irish and other working-class Europeans who would become his core voters loved him":

It was an instructive lesson and a hopeful message with which to begin a series dedicated to cross-cultural exchange.

Following the lecture and discussion, the crowd adjourned to the social hall for tea and home-made scones and musical entertainment.

Coming up next month:

Association co-founder íde B. O'Carroll, speaking in both English and Gaelic, introduced Mr. Cullen, whose credentials include covering the conflict in Northern Ireland for over two decades, Pullitzer-prize-winning reporting of the sex abuse scandals in the Catholic Church, numerous stories and a best-selling book on the hunt for mobster Whitey Bulger, and, most recently, award-winning coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing and trial of the accused perpetrator Dzokhar Tsarnaev.

Mr. Cullen began by reading the Select Board's proclamation of the first annual Irish Day.

The time was roughly divided between the formal talk and a free-ranging discussion with the audience.

Topics that came up in the latter included the changes that Mr. Cullen had seen in Ireland over the years, from the performance of the Irish economy to Sinn Féin's electoral prospects in the south, and closer to home, the Bulger and Tsarnaev trials.

In the context of the latter, Mr. Cullen praised Twitter as a journalist's tool. Although, he quipped, his steady stream of coverage lost him some followers--"People say, 'I don't want 300 tweets a day about some guy picking his nose in the jury box'"--he found it an invaluable way to cover events first as they happen and then in more systematic and distilled fashion afterward. Because it was impossible to provide real-time coverage and take detailed notes at the same time, Twitter in effect became his notebook, for he went back to his Twitter stream and used the tweets as the skeleton for his subsequent full-fledged articles.

Even death is an occasion for a good joke

Known for his dry wit and ironic view of the world as well as his reporting, Mr. Cullen immediately earned a laugh from the audience with a joke about Unitarians. Noting that he was taking a risk by being somewhat mischievous given the setting, he suggested that it was a trait he had inherited from this father. He recalled how, as a Boston Irish Catholic, he first learned about Unitarians. His father took him to the funeral of a fireman acquaintance, who happened to be Unitarian. The boy asked what Unitarians were. The father explained and then said: "You know what you call a Unitarian in a casket? All dressed up and no place to go." During the Q & A, Mr. Cullen managed to find humor in another topic involving mortality. Asked whether he had ever feared for his life while covering the pursuit and trial of notorious mobster and murderer Whitey Bulger, he shrugged, "What's he gonna do--throw a box of Depends at me? He's, like, 84 years old."

Irish-American pols old and new get the job done

The bulk of the formal talk, derived from a Globe piece last fall, was devoted to reflections on the changing profile of the Irish-American politician, from quintessential old-time Boston machine politico James Michael Curley to contemporary figures such as newly elected Boston Mayor Martin Walsh and former Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley (often spoken of as a potential Democratic presidential candidate). There were good reasons and historical circumstances, he said, behind the stereotype of the Irish machine politician.

As Cullen observed, the Irish, having faced vicious discrimination, saw the solution in electing their own. Being a good politician meant providing patronage: getting things done for constituents. At times, this approach collided with the ethics of the system or at least the groups that dominated it.

The clash of cultures was epitomized by the incident in which Mayor Curley impersonated an immigrant in order to take his civil service examination for him. As Cullen explained, "The Brahmins were horrified; the Irish and other working-class Europeans who would become his core voters loved him":

Curley went to jail for that impersonation, but as a political act it was priceless. The good government types were so appalled by Curley’s antics that after he became mayor of Boston in 1914 for the first of four terms, the gentle women of Beacon Hill and the Back Bay descended into the working-class enclaves of Charlestown and South Boston, to promote reform candidates who would beat back the Irish political machine.Later, when the Irish no longer dominated the population, the would-be Irish politician had to come up with a new approach and voter base:

Legend has it that one of these gentle ladies knocked on a door in Southie and was greeted by an Irishwoman holding a wash bucket. The nice lady from Beacon Hill asked the woman of the house to consider voting for her brother, one of the reformers taking on the Curley machine. When asked if her brother would be giving her a job if he won, the gentle lady from Beacon Hill was aghast. “Absolutely not,” she huffed. “That would be improper.”

The lady of the house sniffed, turned up her nose and said, “Why would I vote for a guy who wouldn’t give his own sister a job?”

It has taken more than a generation for this phenomenon to take hold, and in that time the definition of an Irish pol has undergone a massive transformation. Being an Irish pol, for good and bad, has less to do with race and religion, more to do with sensibilities and culture.Cullen pointed to several figures who epitomized this change. State Senator Linda Dorcena Forry, who hosts the annual Saint Patrick's Day brunch, has an old Boston Irish husband--and Haitian parents. However, he singled out the two Martys--Marty Walsh and Marty O'Malley--as exemplars of the transformation. Walsh, he noted, is the first mayor with parents who were not English-speakers: they spoke Gaelic and came to the US only in 1950. Although Walsh is thus among the most "Irish" of politicians, his worldview and politics are anything but inward-looking. He feels close to the Boston Irish, but also to the immigrants from the Caribbean, Latin America, and Asia who make up his working-class constituency. Said Cullen: "He really does identify with minorities, with new immigrants. He says: these are my parents."

It was an instructive lesson and a hopeful message with which to begin a series dedicated to cross-cultural exchange.

* * *

Following the lecture and discussion, the crowd adjourned to the social hall for tea and home-made scones and musical entertainment.

|

| Rosemary Caine plays the harp |

Emma Conrad-Rooney and Delia Mahoney perform Irish dance

Coming up next month:

Antonia Moore (introduced by Sam Hannigan), speaking on:

"From the Blasket Islands, County Kerry, to Hungry Hill, Springfield"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)