Lest one conclude, from recent

posts, that the emphasis here should be exclusively on Japanese atrocities and fanaticism: on the contrary. The intensity of the animosities and combat also elicited behaviors from US forces that we nowadays find hard to contemplate.

For example, the previous post dealt with the rescue of civilians--including a child--from mass suicide attempts that the Japanese military either encouraged or compelled. But as combat dragged on and intensified, US forces became less cautious in the application of force. The Wikipedia entry for the battle of Okinawa--a site from which a great many Americans will presumably get their information--cites this recollection by a soldier:

Earlier

this year, I noted here a piece posted on the tumblr about one of the most

notorious images of US World War II photojournalism. Because we are now

marking the anniversary of the atomic bomb and the end of the Pacific War, I'll reproduce it

here:For example, the previous post dealt with the rescue of civilians--including a child--from mass suicide attempts that the Japanese military either encouraged or compelled. But as combat dragged on and intensified, US forces became less cautious in the application of force. The Wikipedia entry for the battle of Okinawa--a site from which a great many Americans will presumably get their information--cites this recollection by a soldier:

There was some return fire from a few of the houses, but the others were probably occupied by civilians – and we didn't care. It was a terrible thing not to distinguish between the enemy and women and children. Americans always had great compassion, especially for children. Now we fired indiscriminately.

The Bloodiest Battlefield Mementos: Even the “Good War” Had Its Bad Side

Although all war is terrible and we may recoil at the scenes that we see on our televisions and computer screens, the shock is the result of both greater moral sensitivity and continual and less inhibited flow of information (including that from nongovernmental and nonprofessional sources). As I noted in the previous post, we therefore find it all the more difficult to imagine the wars of the past, which were often both more bloody and less explicitly reported.

Even

during World War II–the so-called “Good War”–US troops at times engaged

in behavior that would by our standards (or even those of that day) be

considered barbaric.

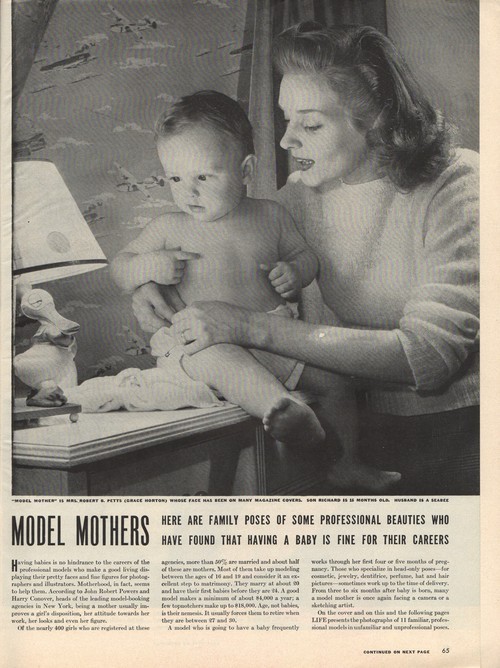

Occasionally, the façade cracked. Consider, for example, the May 22, 1944 issue of Life

Magazine (the leading US photojournalism periodical). The typical

American man or woman settling in for a spell of leisure reading found

on its cover a heartwarming tale of professional success and

domesticity.

[enlarge]

As the title story on page 65 explained, photogenic young women were

finding no contradiction–and indeed, many rewards–in combining

motherhood with modeling. (This was apparently the 1940s privileged

version of “having it all.”).

[enlarge]

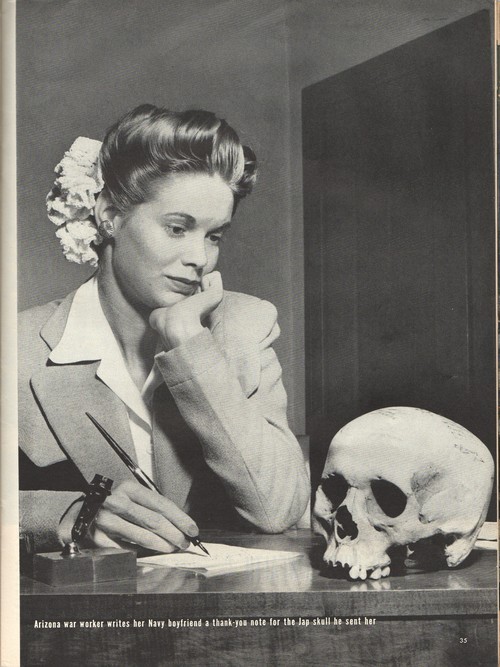

If that reader passed too quickly over page 35, he or she might have

been forgiven for assuming it was part of the title story. It, too,

featured a photograph of a similarly attractive young woman. It’s just

that, rather than holding her baby, she happens to be holding a pen

while contemplating a human skull. The homemaker as Hamlet–but evidently

without the self-scrutiny.

[enlarge]

The caption of this “Picture of the Week” read:

When he said goodby two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends. and inscribed: ‘This is a good Jap–a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach.’ Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

As John Dower wrote in his War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1987), “Life

treated it as a human-interest story, while Japanese propagandists gave

it wide publicity as a revelation of the American national character.”

(65) It was the more ironic given that American propagandists made much

of the sixteenth-century Japanese Hideyoshi’s “ear mound” of 40,000

pickled noses and ears in the wake of war with Korea. (20, 28, 65) As

Dower says, Japanese atrocities accounted for some of the behavior of

the US forces, though not all. In his words:

On the Allied side, some forms of battlefield degeneracy were in fact fairly well publicized while the war was going on. This was especially true of the practice of collecting grisly battlefield trophies from the Japanese dead or near dead, in the form of gold teeth, ears, bones, scalps, and skulls… . [64]

Despite the attention given in Allied propaganda to Hideyoshi’s three-and-a-half-century-old ear mound, in the current war in Asia it was Allied combatants who collected ears. Like collecting gold teeth, this practice was no secret. “The other night,” read an account in the Marine monthly Leatherneck in 1943, “Stanley emptied his pockets of 'souvenirs’–eleven ears from dead Japs. It was not as disgusting, as it would be from a civilian point of view. None of us could get emotional over it.” Even as battle-hardened veterans were assuming that civilians would be shocked by such acts, however, the press in the United States contained evidence to the contrary. In April 1943, the Baltimore Sun ran a story about a local mother who had petitioned authorities to permit her son to mail her an ear she had cut off a Japanese soldier in the South Pacific. She wished to nail it to her front door for all to see. On the very same day, the Detroit Free Press deemed newsworthy the story of an underage youth who had enlisted and 'bribed’ his chaplain not to disclose his age by promising him the third pair of ears he collected. [65]

Dower goes on to say that “Scalps, bones, and skulls were somewhat

rarer trophies, but the latter two achieved special notoriety in both

the United States and Japan” in two cases: first, when a soldier sent

FDR a letter opener made from Japanese bones (the President rejected the

gift), and the second, the aforementioned picture in Life. As Dower further explains:

Most combatants did not engage in such souvenir hunting, and Leatherneck itself published a cartoon which expressed contempt and pity for all scavengers of the dead. At the same time, most fighting men had personal knowledge of such practices and accepted them as inevitable under the circumstances. It is virtually inconceivable, however, that teeth, ears, and skulls could have been collected from German or Italian war dead and publicized in the Anglo-American countries without provoking an uproar; and in this we have yet another inkling of the racial dimensions of the war. [66]War is still hell, but at least this is a circle that we visit less frequently.

2 comments:

Good post as always, Jim. Every spring when my history class gets up to the 1940's I teach a class on the theme of WWII as a Race War, and that image from Life is one of the ones that I show the students. I read Dower's book at Hampshire (I think it was in a class taught by Penina Glazer and Miriam Slater, but I can't remember now) and it made a big impact on me.

I hope you have a great school year!

Thanks, Ethan! I first encountered that book when Aaron and I taught a World War II class back in your day. It is a powerful text (no pun intended). I go back and forth over some of the details, and I know that some other historians have in the meantime come to regard it more critically, but it raises crucial issues in an accessible way and is for that reason well suited to teaching.

Post a Comment