October 29 is the anniversary of the US Historic

Preservation Stamps. What Does Historic Preservation Mean to You Today?

On 15 October 1966, President Lyndon

Johnson signed into law the National Historic Preservation Act, (NHPA; Public Law 89-665; 16 U.S.C. 470 et

seq.), the landmark legislation that, in the words of the National ParkService, “established the framework that focused local, state, and national

efforts on a common goal – preserving the historic fabric of our nation."

Among the results was the creation of the

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the National Register of Historic Places, and enabling legislation

for preservation funding, as well as measures that facilitated the creation of local

historic districts.

To mark the fifth anniversary, the US

Postal Service issued a set of four postage stamps on October 29, 1971.

Designer: Melbourne Brindle

Printing: 150 million in sheets of 32

Decatur House (Washington, DC)

The 1818 building was a fitting choice in several ways. A private domicile, built for the famed American naval hero in the new national “Federal” style in the nation’s capital, it is one of only 3 extant houses by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, architect of the US Capitol. It may have been a more fitting choice than the designers realized: Given to the National Trust in 1956, it acquired landmark status in 1976. Today, as the National Center for White House History, it includes event space for rental as well as commemoration of the enslaved African-Americans who worked and lived here. We thus find here on one site the evolving spectrum of US preservation concerns: historical and architectural significance, cultural diversity and difficult histories, and adaptive reuse.

The last surviving wooden whaling ship, and

a highlight of the historic ensemble of Mystic, CT. An icon of American economic

development and technological achievement.

The iconic local transportation system, which began in 1873 as a creative response to the uniquely hilly terrain. After World War II, the city planned to eliminate them when the bus emerged as a more efficient alternative. Citizen activism saved them from destruction on the grounds of charm and historic resonance in 1947.

(enlarge)

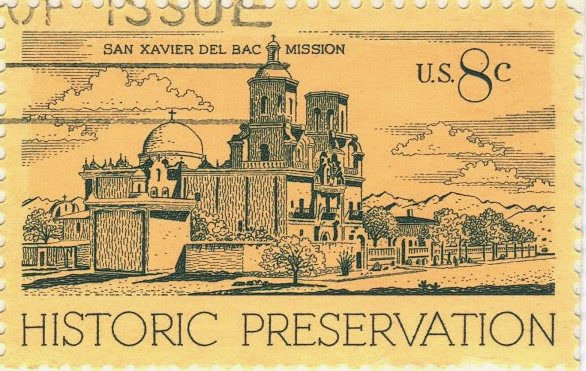

San Xaver Del Bac Mission (near Tuscon)

Reflecting a distinctive blend of aesthetic

influences from Spain, New Spain, and indigenous traditions, it is the oldest

preserved European structure (1783-97) in Arizona, granted landmark status in

1963. Today, we are more willing to acknowledge

the exploitative nature and destructive consequences of the Spanish missionary

work among the Native Americans (1, 2). More generally, we realize that our image

of the old Spanish west derives more from the romanticzing impulses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century than from history itself.

I always show these images at the start of

my historic preservation class—not only as an ice-breaker or eye candy, but

with a further purpose. I ask students to imagine why these images might have

been chosen. That is: what do they tell us about what was valued then?

I have always been intrigued by the

possible logic. There are two sites each

from the east and west coast—though nothing in between (not barn or a Sullivan

skyscraper or a Prairie School house from my native Midwest). The inclusion of the mission broadens the customary scope of preservation concerns to include the Spanish Colonial heritage and moreover adds a religious

structure to the mix. I have always found it noteworthy that, despite the common tendency to associate historic preservation with architecture, half of

the images are not of buildings.

Preservation in the United States, as is well known, began with sites of historical importance to our civic-national narrative and grew to embrace exemplars of architectural distinction. The NHPA formalized the beginning of a greatly

expanded, long-overdue notion of preservation going beyond major landmarks. As the amended

law and practice have evolved, we have come to take a much broader view of

resources and our mission. We preserve vernacular as well as exalted

architecture, we preserve whole neighborhoods as well as individual structures.

We preserve cultural landscapes as well as buildings. We save not only Civil War battlefields, but also once-“futuristic” 1960s gas stations and an early McDonald’s restaurant.

Sometimes (as in the past, no doubt), our

efforts seem to outpace public understanding. We have begun to consider 1950s asphalt parking lots as cultural landscapes. Preservation of a chain link fence in Alexandria, VA became a source of outrage and the butt of jokes not

long ago.

Indeed, as I noted in one of my earliest posts here, the preservation of the modern has

become the most complex and controversial field. Traditionally, preservation

regulations come into effect when a resource is at least 50 years old. However,

given that the middle of the twentieth century witnessed a building boom and

the proliferation of new architectural styles, a vast stock of modernist

structures was or remains unprotected. The fact that many of these styles

lack a popular constituency and that the structures themselves are anything but

energy-efficient puts them in particular jeopardy. The National Park Service

decided that restoration of the landscape of Gettysburg Battlefield trumped

preservation of Richard Neutra’s modernist Cyclorama visitor center.

Protests of architects notwithstanding, the

idiosyncratic Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, too, came down.

On the other hand, whereas concerns over

energy efficiency at times feed the urge for demolition, they now also

contribute to a countervailing trend, as preservationists ally themselves with

environmentalists and sustainability advocates under the mantra, “the greenest building is one that has already been built.”

We have risen up to defend the much-maligned traditional window against the onslaught of the replacement window industry.

The notion of “adaptive reuse” is saving many a building that might otherwise

have fallen to the wrecking ball, even as it prompts us to let go of purist or

absolutist notions of preservation and allow greater changes to structures. (One might perhaps discern a resemblance to the notion of "letting go" and "shared authority" now in vogue in the world of museums and public history.) Often

as not, we now speak of “sustainable preservation" as well as “historic" preservation.

So here’s my question. The fortieth anniversary of the NHPA was cause for both celebration and deliberation. 2016 will mark

the fiftieth anniversary. If we were to issue new preservation stamps two years

from now, what iconic American subjects would you have them depict?

- a Native American burial mound?

- a Colonial New England church?

- a New Orleans “shotgun house”?

- a slave cabin from a southern plantation?

- a barn or silo?

- an old-fashioned divided-light wooden window?

- a New York brownstone?

- a Gilded Age mansion?

- a skyscraper?

- a shopping center or shopping mall?

- the interstate highway system?

- a gas station?

- a drive-in?

- a ranch house or suburban subdivision?

- a one-room schoolhouse?

- a “brutalist” building?

- a Nashville or Detroit recording studio?

- a major-league sports stadium?

or ….?

Please post your answers in the comment

section below. I’m eager to see what, collectively, we come up with.

1 comment:

What better way to acknowledge our nation's significant contributions to music history than by putting a well-known music heritage site on a new historic preservation stamp? My suggestion would be Sun Studio in Memphis, Tennessee. It is a National Historic Landmark, a small and unassuming upholstery shop that became a legendary recording studio of worldwide renown. It represents the democratizing spirit inherent in the architectural legacy of American popular music.

Post a Comment