Both HistoryOrb and POTUS satellite radio chose to mention Abraham Lincoln's so-called "eye for an eye" order. When the Confederate States began maltreating captured African-Americans from the Union Army—enslaving or even executing them—Lincoln responded with his General Order No. 252:

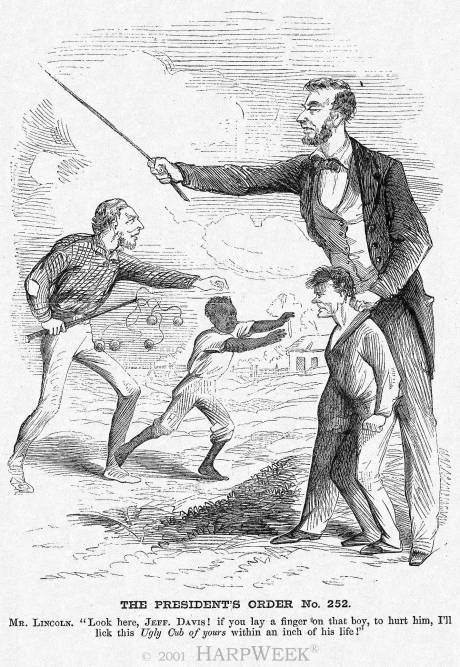

"It is the duty of every Government to give protection to its citizens, of whatever class, color or condition, and especially to those who are duly organized as soldiers in the public service. The law of nations, and the usages and customs of war, as carried on by civilized powers, permit no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war as public enemies. To sell or enslave any captured person on account of his color, and for no offense against the laws of war, is a relapse into barbarism, and a crime against the civilization of the age."On August 15, Harpers published the following cartoon:

"The Government of the United States will give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave any one because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy's prisoners in our possession. It is therefore ordered, that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the law, a Rebel soldier shall be executed, and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a Rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works, and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war."

HarpWeek explains, inter alia:

Lincoln's retaliatory order was difficult to put into practice. After a massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow (April 12, 1864), the president and his military advisors decided to punish the Confederates directly responsible, should they be captured, rather than to randomly execute a corresponding number of Confederate prisoners of war. Field commanders near Richmond, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina carried out the Union’s only official retaliations. When Confederates forced captured black soldiers to build fortifications in the line of fire, the Union officers made an equal number of Confederate prisoners perform similar work. Thereafter, the Confederates stopped the practice.What the Harper's website does not mention is that Lincoln came to his policy only after a period of inaction. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who viewed black recruitment in the northern war effort as a touchstone of equality, was dismayed that the government was slow in instituting it and even then, did not give the soldiers full equal rights. Concerning the southern threat of retribution, David Blight (now of Yale, formerly our colleague at Amherst College) explains:

The Confederacy’s refusal to acknowledge captured black servicemen as legitimate prisoners of war halted prisoner-of-war exchanges in the summer of 1863. By the end of the year, the Confederacy was willing to discuss returning black soldiers who upon enlistment had been legally free as the Confederacy defined it (i.e., not under the Emancipation Proclamation). That position was not sufficient for top Union officials--President Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and General Ulysses S. Grant--who remained steadfastly committed to ensuring the equal treatment of Union prisoners of war. Davis and Confederate officials finally relented in January 1865, agreeing to exchange all prisoners. A few thousand prisoners of war, including freed slaves, were exchanged by the Confederacy and Union until the end of the war in April.

The Union government’s apparent lack of response to this harsh treatment angered Douglass even further. In two editorials written sometime in late July, he viciously attacked Lincoln’s silence on Confederate killings of black prisoners, as well as threats of their enslavement. ‘The slaughter of blacks taken as captives,’ wrote an outraged Douglass, ‘seems to affect him [Lincoln] as little as the slaughter of beeves for the use of his army.' Douglass wanted an eye for an eye—one southerner put to death for every black soldier killed as a prisoner of war. Lincoln, like most northern leaders, had little stomach for this kind of retaliation, Douglass suggested, but these threats did not go unanswered. Two weeks after the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina (which occurred on July 18, 1863), where many black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts were slain or captured, Lincoln issued his retaliatory order.Be that as it may, I've always regarded the order as one of the most fascinating documents of the era, worthy to stand beside the far better-known Emancipation Proclamation as a milestone in the movement toward racial equality. It is a severe and imposing milestone, to be sure. Indeed, it reminds one of Robespierre’s belief that "justice, prompt, severe, inflexible" was the order of the day in times of revolution and civil war. (incidentally, Lincoln's opponents sometimes compared him to Robespierre.) But at a time when even the 179,000 black Union soldiers were denied equal pay as well as the right to become officers, the order put into practice the principle of full equality by stating that the lives of blacks and whites were of the same value and it demanded that the Confederacy, too, acknowledge this—or pay the price.

It is therefore interesting to consider, too, the biblical phrase, "an eye for an eye" (literally: an eye under an eye) which, as I often have to point out to students and others (sometimes: ministers), has long been misused to imply instinctive and primitive vengeance or "tit for tat" response. Derived from several scriptural passages, it in fact is nothing of the sort. Rather, this so-called lex talionis, or law of retaliation (sorry, nothing to do with bloody talons or claws), represented a step up in the scale of moral sensitivity, in three regards. First, it stood for the principle that the crime must fit and not exceed the punishment. Second, it was never intended to be taken literally, much less, applied in that manner. it was therefore a symbolic representation of the demand for appropriate monetary compensation. (1, 2) Third, as my old friend and medievalist colleague Richard Landes points out, even in this latter regard it was distinctive and unusually advanced in its day in that it was truly egalitarian. Unlike other ancient and even medieval codes of justice (remember that paragraph on the weregild or wergeld from your high school or college history textbooks?), it provided for equal compensation for all, regardless of social class. Understood in that context, then, the phrase as applied to Lincoln's order at least reflects the principle of equality that, in the mind of Douglass, it was intended to enforce.

Impossible, for better or worse, to imagine any leader of a major country publicly issuing such an order nowadays, even apart from the fact that Lincoln was acting before all the major international agreements codified and strengthened the customary laws of war (for example, the first Hague Convention dates from 1899, and the first Geneva Convention, on the wounded and the sick, from 1864).

Consider, too, these passages from Francis Lieber's pathbreaking "Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field," issued as Lincoln's Order No. 100, 24 April 1863:

Art. 27.

The law of war can no more wholly dispense with retaliation than can the law of nations, of which it is a branch. Yet civilized nations acknowledge retaliation as the sternest feature of war. A reckless enemy often leaves to his opponent no other means of securing himself against the repetition of barbarous outrage

Art. 28.

Retaliation will, therefore, never be resorted to as a measure of mere revenge, but only as a means of protective retribution, and moreover, cautiously and unavoidably; that is to say, retaliation shall only be resorted to after careful inquiry into the real occurrence, and the character of the misdeeds that may demand retribution.

Unjust or inconsiderate retaliation removes the belligerents farther and farther from the mitigating rules of regular war, and by rapid steps leads them nearer to the internecine wars of savages.

Art. 29.

Modern times are distinguished from earlier ages by the existence, at one and the same time, of many nations and great governments related to one another in close intercourse.

Peace is their normal condition; war is the exception. The ultimate object of all modern war is a renewed state of peace.

The more vigorously wars are pursued, the better it is for humanity. Sharp wars are brief.

Art. 30.Here we see the jurist and philosopher wrestling with the twin facts that humanity imposes new demands upon the makers of war even as war, though seen as exceptional and undesirable, has begun to become total war. In the words of Roza Pati, "this Lieber Code would come to constitute the roots of what was later called humanitarian law," for example with regard to humane treatment of prisoners.

Ever since the formation and coexistence of modern nations, and ever since wars have become great national wars, war has come to be acknowledged not to be its own end, but the means to obtain great ends of state, or to consist in defense against wrong; and no conventional restriction of the modes adopted to injure the enemy is any longer admitted; but the law of war imposes many limitations and restrictions on principles of justice, faith, and honor.

Consider again these lines from Lieber:

Peace is their normal condition; war is the exception. The ultimate object of all modern war is a renewed state of peace.Almost impossible to imagine any major leader nowadays making that latter statement, either, but it brings home the paradox. Today, we seem to face the prospect of endless low-intensity warfare. New forms of war and new rules of engagement lead to new dilemmas concerning the conduct and ends of war, and the rights of soldier and civilian alike.

The more vigorously wars are pursued, the better it is for humanity. Sharp wars are brief.

I am left with the question: to what extent have we really advanced? As so often, the dilemmas of Lincoln and his age seem very close to our own.

No comments:

Post a Comment