Speaking of the history of our flag: Fifty years ago this weekend, the "star-spangled banner" acquired its last star, when Hawaii joined the union as the fiftieth state.

TV 22 (WWLP) in Springfield has a nice little photo display on the historical evolution of our national flag.

"In fiction, the principles are given, to find

the facts: in history, the facts are given,

to find the principles; and the writer

who does not explain the phenomena

as well as state them performs

only one half of his office."

Thomas Babington Macaulay,

"History," Edinburgh Review, 1828

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Monday, June 28, 2010

28 June 1914: The Assassination at Sarajevo; countdown to World War I

On this date in 1914, Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo.

The Austrian aesthete Stefan Zweig recalled, in his classic memoir, The World of Yesterday (1943), how the news reached him as he spent his vacation in Baden, near Vienna. In the midst of the popular celebrations on the 29th, a religious feastday, a concert in the park suddenly broke off and people stopped moving. A crowd gathered around a placard:

What is more, even the political fallout was at first minimal, and even the dynasty seemed more concerned with social etiquette than revenge:

Like many contemporaries, Zweig felt compelled to remark in his recollections upon the unusually fair weather:

uniforms, dress, and other personal belongings of

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, with relics

from the assassinat

60th anniversar

Czech National Museum, 2009

The Austrian aesthete Stefan Zweig recalled, in his classic memoir, The World of Yesterday (1943), how the news reached him as he spent his vacation in Baden, near Vienna. In the midst of the popular celebrations on the 29th, a religious feastday, a concert in the park suddenly broke off and people stopped moving. A crowd gathered around a placard:

It was, as I soon learned, the text of a telegram announcing that His Imperial Majesty, the successor to the crown, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, who had gone to the maneuvers in Bosnia, had fallen victims of a political assassination there.The reaction was not what our textbooks and popular culture lead us to believe. He recalled popular shock but no real empathy: Franz Ferdinand was not well liked, and "There were many on that day in Austria who secretly sighed with relief that this heir of the aged Emperor had been removed in favor of the much more beloved young Archduke Karl."

What is more, even the political fallout was at first minimal, and even the dynasty seemed more concerned with social etiquette than revenge:

Of course the newspapers printed lengthy eulogies on the following day, giving fitting expression to their indignation over the assassination. But there was no indication that the event was to be used politically against Serbia. The immediate concern of the Imperial house was quite another one, namely the solemn obsequies.The burning question was not war vs. peace, but rather: would Franz Ferdinand's wife, Countess Chotek, who was of inferior social rank, be granted interment in the Imperial crypt of the Habsburgs?

Like many contemporaries, Zweig felt compelled to remark in his recollections upon the unusually fair weather:

The summer was beautiful as never before and promised to become even more beautiful—and we all looked out upon the world without a care. I can recall that on my last day in Baden I was walking through the vineyards with a friend, when an old wine-grower said to us: 'We haven't had such a summer for a long time. If it stays this way, we'll get better grapes than ever. Folks will remember this summer!'The beauty of the summer assumed such prominence in so many recollections not only because it was in fact remarkable, but above all, because it came to epitomize the ironic distance between prewar innocence and wartime horror. As Paul Fussell observed in his now-classic The Great War and Modern Memory (1975):

He did not know, the old man in his blue cooper's smock, how gruseomely true a word he had spoken.

Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected. Every war constitutes an irony of situation because its means are so melodramatically disproportionate to its presumed ends. In the Great War eight million people were destroyed because two persons, the Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his Consort, had been shot . . . .

But the Great War was more ironic than any before or since. It was a hideous embarrassment to the prevailing Meliorist myth which had dominated the public consciousness for a century. It reversed the Idea of Progress.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

June 21, 1768: Future Massachusetts Revolutionary Trash-Talks the (British) Government

From back in the time when people could take politics and political discourse seriously.

In today's "Mass Moment," the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities tells us:

Those who worry so much about the level of "civility" in politics today could put their minds at ease if they gained a bit of historical perspective—or just watched today's sessions of the same British Parliament that Otis attacked. In any case, it's the intellectual quality of the discourse that we should worry about.

In today's "Mass Moment," the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities tells us:

...in 1768, James Otis, Jr. gave a characteristically fiery speech to his fellow legislators in Boston. He referred to the British House of Commons as a gathering of "button-makers, horse jockey gamesters, pensioners, pimps, and whore-masters." The colony's royal governor denounced Otis's tirade as the most "insolent. . . treasonable declamation that perhaps was ever delivered." Otis's speech in June 1768 was one of many that attacked Parliament for its efforts to squeeze more revenue from the American colonies. His insistence that "a man's house is his castle" and later that there be "no taxation without representation" remain etched in our collective memory long after his name, and his role in the events leading up to the Revolution, have been forgotten. (read the rest)

Those who worry so much about the level of "civility" in politics today could put their minds at ease if they gained a bit of historical perspective—or just watched today's sessions of the same British Parliament that Otis attacked. In any case, it's the intellectual quality of the discourse that we should worry about.

Monday, June 21, 2010

Collateral Damage: “Gaza Freedom Flotilla” Torpedoes Divestment Rationale

It was to be expected that the recent clash in the Mediterranean would reawaken debate over the ethics and efficacy of both Israel’s closure of Gaza and anti-Israel activist movements that backed the disastrous "flotilla" enterprise. What was perhaps not to be expected was that, amidst the rising tide of information, two minor but telling pieces of evidence could serve as textbook illustrations of the inanity and hollowness of the divestment movement here at home. First, the context.

The intense struggle over assertion of both facts and interpretation in the wake of Gaza flotilla fracas has produced an intriguing situation for the scholar of history and communications, as both new forces and new communication techniques assumed a larger role in the fray. It’s a phenomenon that arguably began in earnest with the 2006 Lebanon war, when bloggers came into their own, filling a vacuum left by both the state actors and their opponents, on the one hand, and the mainstream media, on the other. The pattern evolved further with “Operation Cast Lead” in 2008-9, as both official and irregular forces on each side began to make even more extensive use of new venues and social media, from Twitter to YouTube.

In the present case, we saw a simple and at first uncritically accepted narrative—armed soldiers enforcing an illegal and inhumane policy massacre unarmed humanitarian activists (indeed, this was the precise message of a sermon preached in a local liberal church; with the added tonic: and yet we hesitate to speak these truths for fear of being called antisemites)—began to yield to a more complex and ambiguous picture. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

Almost immediately, the fight over the interpretation of the fighting took on a life of its own, waged either on the basis of the new evidence or in an attempt to discount it by changing the terms of debate. (Thus, claims that one side was winning the media war might in fact be an attempt to show that it had “really” lost. (1, 2, 3, 4)

Every detail of every statement or image was highlighted, scrutinized, debated. For example, when Israel Defense Forces (IDF) took control of the “Mavi Marmara”—the only one of the six ships on which a violent confrontation occurred—they cited as evidence in support of their argument that the “activists” came prepared for combat the discovery of knives, clubs, slingshots, stun grenades, ceramic vests, and night vision goggles.

Flash back to the divestment controversy at Hampshire College last year. As readers will recall (and be tired of hearing, I can only hope), Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) falsely claimed that they had manfully forced the administration to divest from "the Israeli occupation of Palestine." No such thing in fact took place. In its failed attempt, SJP focused on six corporations that have become popular targets elsewhere. It used the list developed by the New England Conference of the Methodist Church (further proof, if any was needed, that religious groups should not meddle in areas in which they have no competence—which is to say almost everything).

Thus we find ITT pilloried for supplying components of “night vision goggles,” which, the rather clumsily worded document explains, “enable Israel to attack refugee camps and villages in the middle of the night, the time when many of these raids and assaults take place.” The statement is misleading as well as redundant. Even leaving aside the defamatory suggestion that the IDF would deliberately attack civilian “refugee camps and villages,” as such—rather than combatants located there—the fact remains that night vision devices have many purposes. They can be used by troops of any nation in a legitimate military activity: ITT supplies them to the armed forces of US, UK, and Canada. They also play a vital role in search-and rescue operations for victims of airplane crashes and shipwrecks, lost hikers, and other civilians. In fact, ITT equipment enabled police to locate and save victims of Hurricane Katrina.

But wait a minute: Did you say, "night vision goggles"?

Yes, I did.

For the IDF, the presence of the night-vision equipment on board the "Mavi Marmara" was, in context, just one more piece of evidence confirming the conclusion that trained and armed Jihadi activists planned for violence from the start. Supporters of the flotilla scoffed at this logic. One widely-quoted blogger sneered at "exhibit F: night vision equipment, of course utterly useless on high seas." This analysis would come as a surprise to the maritime rescue forces that regularly use the devices—or, indeed, to the flotilla supporters who demanded that our government investigate whether the use of US-supplied equipment, from helicopters to—guess what?—"night vision goggles," in "Israel's act of aggression on the high seas" violated the Arms Export Control Act.

The IDF concluded that the violent Jihadis, who forced the naïve peaceful participants to remain on the lower levels of the ship, were "split into a number of squads of about 20 mercenaries each distributed throughout the upper deck":

Indeed.

It just so happens that another divestment target at Hampshire College was Motorola, which activists (again, following their Methodist models) selected because it provides “radar systems for enhancing security at illegal West Bank settlements” (no idea what that means) and supplies the IDF with “advanced“ “cell phone communications” (quelle horreur) and “encrypted wireless communication . . . that will enable military use in the occupied territories and other remote areas.” "Wireless"? Yes, tough to find a pay phone when you're in combat. "Encrypted"? Well, armies generally prefer secure communications in the field, wherever that may be. "Remote"? Do these guys know anything about geography? The combined area of the State of Israel and the territories is about the size of Maryland, and the distance from the Jordan River to the sea is only 40 miles. "Other remote areas"? That would best apply to the Negev desert, but that's been part of Israel from the start. But "other" implies they're not "occupied," so presumably that's not a problem—unless you're opposed to the state and its right to self-defense, as such. (But I digress; this is not the sort of thing capable of withstanding rational analysis.)

I mentioned ITT and Katrina rescue efforts above. Well, it turns out (more bad news) that Motorola was even more deeply involved: it established "a $1 million education fund to help rebuild schools and educate displaced children in the region," and contributed another half a million dollars in further relief efforts, including donations of both equipment and cash. Perhaps, in their panic, the Katrina victims in the Gentilly district of New Orleans, trapped by both flood and looters, forgot to check for the ITT label on the SWAT team's night vision equipment before they consented to be rescued. And perhaps their friends and neighbors elsewhere in the hurricane-ravaged south were too busy rebuilding their shattered lives and homes, and just didn't have time to read the moralizing advice of Methodists and Massachusetts activists and learn that Motorola also sold stuff to evil Zionists.

Or: is all forgiven now that these products have received the de facto endorsement of the "Free Gaza Movement" (I can just imagine the testimonials; that's an invitation) and the kosher certificate from anti-Israel bloggers everywhere?

Well, "humanitarian activist" dudes, which is it: Are night vision equipment and walkie-talkies a tool of oppressive occupation or a weapon of the forces of freedom?

Sound confusing? That’s precisely my point: Often, the same product can be used for a wide range of purposes, and intention and context are everything (anyone can buy a butcher knife; anyone using that knife to stab someone may be guilty of a crime). To target the manufacturer, absent some very specific and compelling connection, is both unjustified and pointless. And that's the point, too: As even sharp but honest critics of Israel will admit, the BDS movement's divestment campaign is not about ending the "occupation" or bringing about "peace": it's about symbolic political victories whose real aim is the delegitimization and ultimate dissolution of a United Nations member state. The divestment game is just that: a game, and a rigged one at that.

But to return from the Mediterranean to Massachusetts. What happened at Hampshire College?

It did not "divest from Israel" or even "the Israeli occupation of Palestine" in any way. Rather, it duly forwarded the divestment request to the Trustees' investment committee, which found that numerous firms in the given portfolio violated the College's socially responsible investment policy, based on such issues as "employment discrimination, environmental abuse, military weapons manufacturing, unsafe workplace settings, and dealings with Burma or Sudan." Of the six targeted firms, one was not even part of the fund in question, and two—one of which was Motorola—"were given a clean bill of health on Hampshire's policy." Ironically, Motorola was the only one of the six firms for which activists cited even the remotest explicit “settlement” connection. The rest all produced equipment that—like the other Motorola products cited—could be used, in the territories or elsewhere, for legitimate or illegitimate military purposes.

SJP responded, "a week ago Hampshire College was invested in the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Today, the college is no longer complicit in the funding of this injustice." As I (and others) have repeatedly pointed out, this is laughable. In the face of the rejection of the divestment claim by all responsible voices, SJP has subsequently adopted the lame, utterly vague, and increasingly desperate assertion that "divestment still is a statement." (Huh?)

But since this is a game, let's play along with the logic.

Hampshire College is still invested in Motorola. SJP claimed that Motorola was complicit in the occupation. Ergo, Hampshire is in fact still invested in the occupation. Now, however, it turns out that the Freedom Flotilla activists saw no problem in using Motorola devices to resist IDF forces. Will SJP now change its tune and suddenly spin this as evidence of the College’s investment in support of the “Free Gaza” movement?

Nothing would surprise me anymore. Stay tuned.

The intense struggle over assertion of both facts and interpretation in the wake of Gaza flotilla fracas has produced an intriguing situation for the scholar of history and communications, as both new forces and new communication techniques assumed a larger role in the fray. It’s a phenomenon that arguably began in earnest with the 2006 Lebanon war, when bloggers came into their own, filling a vacuum left by both the state actors and their opponents, on the one hand, and the mainstream media, on the other. The pattern evolved further with “Operation Cast Lead” in 2008-9, as both official and irregular forces on each side began to make even more extensive use of new venues and social media, from Twitter to YouTube.

In the present case, we saw a simple and at first uncritically accepted narrative—armed soldiers enforcing an illegal and inhumane policy massacre unarmed humanitarian activists (indeed, this was the precise message of a sermon preached in a local liberal church; with the added tonic: and yet we hesitate to speak these truths for fear of being called antisemites)—began to yield to a more complex and ambiguous picture. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

Almost immediately, the fight over the interpretation of the fighting took on a life of its own, waged either on the basis of the new evidence or in an attempt to discount it by changing the terms of debate. (Thus, claims that one side was winning the media war might in fact be an attempt to show that it had “really” lost. (1, 2, 3, 4)

Every detail of every statement or image was highlighted, scrutinized, debated. For example, when Israel Defense Forces (IDF) took control of the “Mavi Marmara”—the only one of the six ships on which a violent confrontation occurred—they cited as evidence in support of their argument that the “activists” came prepared for combat the discovery of knives, clubs, slingshots, stun grenades, ceramic vests, and night vision goggles.

Flash back to the divestment controversy at Hampshire College last year. As readers will recall (and be tired of hearing, I can only hope), Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) falsely claimed that they had manfully forced the administration to divest from "the Israeli occupation of Palestine." No such thing in fact took place. In its failed attempt, SJP focused on six corporations that have become popular targets elsewhere. It used the list developed by the New England Conference of the Methodist Church (further proof, if any was needed, that religious groups should not meddle in areas in which they have no competence—which is to say almost everything).

Thus we find ITT pilloried for supplying components of “night vision goggles,” which, the rather clumsily worded document explains, “enable Israel to attack refugee camps and villages in the middle of the night, the time when many of these raids and assaults take place.” The statement is misleading as well as redundant. Even leaving aside the defamatory suggestion that the IDF would deliberately attack civilian “refugee camps and villages,” as such—rather than combatants located there—the fact remains that night vision devices have many purposes. They can be used by troops of any nation in a legitimate military activity: ITT supplies them to the armed forces of US, UK, and Canada. They also play a vital role in search-and rescue operations for victims of airplane crashes and shipwrecks, lost hikers, and other civilians. In fact, ITT equipment enabled police to locate and save victims of Hurricane Katrina.

But wait a minute: Did you say, "night vision goggles"?

Yes, I did.

For the IDF, the presence of the night-vision equipment on board the "Mavi Marmara" was, in context, just one more piece of evidence confirming the conclusion that trained and armed Jihadi activists planned for violence from the start. Supporters of the flotilla scoffed at this logic. One widely-quoted blogger sneered at "exhibit F: night vision equipment, of course utterly useless on high seas." This analysis would come as a surprise to the maritime rescue forces that regularly use the devices—or, indeed, to the flotilla supporters who demanded that our government investigate whether the use of US-supplied equipment, from helicopters to—guess what?—"night vision goggles," in "Israel's act of aggression on the high seas" violated the Arms Export Control Act.

The IDF concluded that the violent Jihadis, who forced the naïve peaceful participants to remain on the lower levels of the ship, were "split into a number of squads of about 20 mercenaries each distributed throughout the upper deck":

T. said he realized the group they were facing was well-trained and likely ex-military after the commandos threw a number of stun grenades and fired warning shots before rappelling down onto the deck. “They didn’t even flinch,” he said. “Regular people would move.”Did he just say, "Motorola"?

Each squad of the “mercenaries” was equipped with a Motorola communication device, the IDF said, so they could pass information to one another. Assessments in the defense establishment are that members of the group were affiliated with international global jihad elements and had undergone training in places like Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Indeed.

It just so happens that another divestment target at Hampshire College was Motorola, which activists (again, following their Methodist models) selected because it provides “radar systems for enhancing security at illegal West Bank settlements” (no idea what that means) and supplies the IDF with “advanced“ “cell phone communications” (quelle horreur) and “encrypted wireless communication . . . that will enable military use in the occupied territories and other remote areas.” "Wireless"? Yes, tough to find a pay phone when you're in combat. "Encrypted"? Well, armies generally prefer secure communications in the field, wherever that may be. "Remote"? Do these guys know anything about geography? The combined area of the State of Israel and the territories is about the size of Maryland, and the distance from the Jordan River to the sea is only 40 miles. "Other remote areas"? That would best apply to the Negev desert, but that's been part of Israel from the start. But "other" implies they're not "occupied," so presumably that's not a problem—unless you're opposed to the state and its right to self-defense, as such. (But I digress; this is not the sort of thing capable of withstanding rational analysis.)

I mentioned ITT and Katrina rescue efforts above. Well, it turns out (more bad news) that Motorola was even more deeply involved: it established "a $1 million education fund to help rebuild schools and educate displaced children in the region," and contributed another half a million dollars in further relief efforts, including donations of both equipment and cash. Perhaps, in their panic, the Katrina victims in the Gentilly district of New Orleans, trapped by both flood and looters, forgot to check for the ITT label on the SWAT team's night vision equipment before they consented to be rescued. And perhaps their friends and neighbors elsewhere in the hurricane-ravaged south were too busy rebuilding their shattered lives and homes, and just didn't have time to read the moralizing advice of Methodists and Massachusetts activists and learn that Motorola also sold stuff to evil Zionists.

Or: is all forgiven now that these products have received the de facto endorsement of the "Free Gaza Movement" (I can just imagine the testimonials; that's an invitation) and the kosher certificate from anti-Israel bloggers everywhere?

Well, "humanitarian activist" dudes, which is it: Are night vision equipment and walkie-talkies a tool of oppressive occupation or a weapon of the forces of freedom?

Sound confusing? That’s precisely my point: Often, the same product can be used for a wide range of purposes, and intention and context are everything (anyone can buy a butcher knife; anyone using that knife to stab someone may be guilty of a crime). To target the manufacturer, absent some very specific and compelling connection, is both unjustified and pointless. And that's the point, too: As even sharp but honest critics of Israel will admit, the BDS movement's divestment campaign is not about ending the "occupation" or bringing about "peace": it's about symbolic political victories whose real aim is the delegitimization and ultimate dissolution of a United Nations member state. The divestment game is just that: a game, and a rigged one at that.

But to return from the Mediterranean to Massachusetts. What happened at Hampshire College?

It did not "divest from Israel" or even "the Israeli occupation of Palestine" in any way. Rather, it duly forwarded the divestment request to the Trustees' investment committee, which found that numerous firms in the given portfolio violated the College's socially responsible investment policy, based on such issues as "employment discrimination, environmental abuse, military weapons manufacturing, unsafe workplace settings, and dealings with Burma or Sudan." Of the six targeted firms, one was not even part of the fund in question, and two—one of which was Motorola—"were given a clean bill of health on Hampshire's policy." Ironically, Motorola was the only one of the six firms for which activists cited even the remotest explicit “settlement” connection. The rest all produced equipment that—like the other Motorola products cited—could be used, in the territories or elsewhere, for legitimate or illegitimate military purposes.

SJP responded, "a week ago Hampshire College was invested in the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Today, the college is no longer complicit in the funding of this injustice." As I (and others) have repeatedly pointed out, this is laughable. In the face of the rejection of the divestment claim by all responsible voices, SJP has subsequently adopted the lame, utterly vague, and increasingly desperate assertion that "divestment still is a statement." (Huh?)

But since this is a game, let's play along with the logic.

Hampshire College is still invested in Motorola. SJP claimed that Motorola was complicit in the occupation. Ergo, Hampshire is in fact still invested in the occupation. Now, however, it turns out that the Freedom Flotilla activists saw no problem in using Motorola devices to resist IDF forces. Will SJP now change its tune and suddenly spin this as evidence of the College’s investment in support of the “Free Gaza” movement?

Nothing would surprise me anymore. Stay tuned.

Labels:

BDS,

Embarrassing Amherst,

Hampshire College,

Middle East,

SJP

Sunday, June 20, 2010

20 June 1898: Conservation Landmark, as Massachusetts Establishes its First State Park at Mount Greylock (and lessons for conservationists)

On this day in 1898, Mass Moments tells us:

Clear-cutting of one side of the mountain by loggers prompted local businessmen to form an association to purchase the land at the peak and attempt to maintain it by charging fees for recreational access, thus combining preservation and profit. (One also thinks of related civic efforts of the era, such as our own Amherst Village Improvement Society and Ornamental Tree association). When the profits failed to materialize, the businessmen (helped by new environmental lobbying efforts) persuaded the state to purchase the site and surrounding area. Sound familiar?

Most of Massachusetts had been stripped of trees by the 1830s, the land cleared for agriculture and the wood used for construction and fuel. After farming declined in the second half of the nineteenth century, the resultant second growth pine forest came to appear as a valuable source of lumber, and other , leading to irresponsible clearance. By the end of the twentieth century, forest area in Massachusetts was actually greater than it had been in the Colonial era, but just around that time, according to a new report from the Harvard Forest, it began another downward turn, due to pressures from development. It is ironic: the early settlers and their descendants at times acted as if resources were unlimited and took few if any deliberate steps to replenish them, and in a sense one can hardly blame them. To them, the lush greenness and low population density of New England must have seemed a paradise of inexhaustible materials in comparison with a crowded and deforested Europe. The virgin forests of the Americas were said to be so dense that a squirrel could walk across the tops of the trees from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. The oft-cited statement is untrue, but it thus all the more accurately highlights the mentality. We today are much more aware of the fragility of the environment and finitude of resources, and yet the problem today is that the ecological threats are both more serious and more enduring. Ironically, the threat is not from foresters, who today both hold onto land and replant it (another salutary warning for those who leap to conclusions based on stereotypes). Instead, it comes from developers in real estate and other commercial endeavors, who purchase land for short periods of time and then resell it. And, whereas abandoned farms of the era 1830-50 easily reverted to woodland, shopping malls and housing subdivisions do not.

As Harvard Forest Director David Foster said,

...in 1898, the legislature established the first state park in Massachusetts on Mount Greylock. The tallest peak in the state, at almost 3500 feet, Greylock is like an island, different in geology, climate and ecology from its Berkshire County surroundings. But its isolation did not protect it. By the late 1800s, unregulated logging threatened to deforest its slopes. In 1885 a group of concerned citizens bought 400 acres around the summit. In 1898 they turned the land over to the state to protect it forever. In the years since then, the Commonwealth has added 285,000 acres to the state park system, 12,500 of them on Mt. Greylock, making the Massachusetts state park system the ninth largest in the country. (read the rest)As the essay tells us, concern over preservation of the environment or natural landscape is nothing new, at least by the average person's time scale (for historians, this is still relatively recent).

Clear-cutting of one side of the mountain by loggers prompted local businessmen to form an association to purchase the land at the peak and attempt to maintain it by charging fees for recreational access, thus combining preservation and profit. (One also thinks of related civic efforts of the era, such as our own Amherst Village Improvement Society and Ornamental Tree association). When the profits failed to materialize, the businessmen (helped by new environmental lobbying efforts) persuaded the state to purchase the site and surrounding area. Sound familiar?

Most of Massachusetts had been stripped of trees by the 1830s, the land cleared for agriculture and the wood used for construction and fuel. After farming declined in the second half of the nineteenth century, the resultant second growth pine forest came to appear as a valuable source of lumber, and other , leading to irresponsible clearance. By the end of the twentieth century, forest area in Massachusetts was actually greater than it had been in the Colonial era, but just around that time, according to a new report from the Harvard Forest, it began another downward turn, due to pressures from development. It is ironic: the early settlers and their descendants at times acted as if resources were unlimited and took few if any deliberate steps to replenish them, and in a sense one can hardly blame them. To them, the lush greenness and low population density of New England must have seemed a paradise of inexhaustible materials in comparison with a crowded and deforested Europe. The virgin forests of the Americas were said to be so dense that a squirrel could walk across the tops of the trees from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. The oft-cited statement is untrue, but it thus all the more accurately highlights the mentality. We today are much more aware of the fragility of the environment and finitude of resources, and yet the problem today is that the ecological threats are both more serious and more enduring. Ironically, the threat is not from foresters, who today both hold onto land and replant it (another salutary warning for those who leap to conclusions based on stereotypes). Instead, it comes from developers in real estate and other commercial endeavors, who purchase land for short periods of time and then resell it. And, whereas abandoned farms of the era 1830-50 easily reverted to woodland, shopping malls and housing subdivisions do not.

As Harvard Forest Director David Foster said,

Though today’s forests are predominantly second growth and different in character from the region’s original forests, researchers said area residents have a second chance to decide their forests’ fate. The first Colonial-era settlers decided to cut them down, but now that the forests have re-grown, it’s our turn to make a similar choice.Now, as in the days when Greylock was saved, conservation groups are mobilizing, but that's not enough:

The group called for cooperation across the region, in both the public and private sectors, to bring the report’s vision to reality. . . . While cooperation is needed, increased public funding also will be important, since many property owners in rural areas are “land rich” but not wealthy and so can’t turn over land or development rights without compensation.Plus ça change.

"Juneteenth" (19 June 1865): Freedom for African-Americans

On this date in 1865, at the end of the Civil War, Union troops in Texas informed enslaved African-American that they were henceforth free. The date has become a holiday (marked today in 36 US states) celebrating freedom for African-Americans.

Ralph Ellison entitled his long-awaited novel—pubished only posthumously,years after his celebrated Invisible Man—Juneteenth (1999).

Celebrations are often an occasion to honor local community members. In Springfield this year,

Ralph Ellison entitled his long-awaited novel—pubished only posthumously,years after his celebrated Invisible Man—Juneteenth (1999).

Celebrations are often an occasion to honor local community members. In Springfield this year,

The father of murder victim Mario Hornsby Junior, and the mother of the boy who had taken his own life as victim of bullying, were honored for trying to improve conditions that had led to their personal losses.

Friday, June 18, 2010

18 June 1942: Nazis Kill Heydrich Assassins in Bloody Church Shootout

As soon as Czech parachutists Josef Valčik, Jan Kubiš, and Josef Gabčík, launched their attempt on the life of the Nazi "Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia," SS Lt. General Reinhard Heydrich (full story here) on May 27, 1942, they became the subjects of the largest and most vicious manhunt in occupied Europe. The hunt was accompanied by unprecedented terror (the so-called Heydrichiade), almost all of it directed against the innocent: most infamously, the gratuitous destruction of the village of Lidice.

The three men and their comrades from the other parachute teams at first went underground in safe houses, but as conditions became too dangerous, they found refuge in the crypt of the Orthodox Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius (named after the apostles to the Slavs). (The Germans persisted in calling it by the older name of Karel Borromeus Church, after the saint Carlo Borromeo, of the Counter-Reformation era, when Bohemia was forcibly recatholicized.) As the terror mounted, the parachutists were tormented by feelings of guilt and considered confessing and then committing suicide. Ultimately, they were persuaded to continue resistance, not least because there was no evidence that surrender would stop the reprisals.

By mid-June, just as there was hope (some realistic, most of it fanciful) that the parachutists would be able to flee the country, they were betrayed by one of their own, Karel Čurda, who, depending on which sources one believes, was moved by a combination of fear, anguish over the reprisals (including threats to his own family), and greed: the Nazis were offering a reward of 10 million Czech Crowns (1 million German Reichsmark) for information leading to the assassins. He identified the assassins but did not know their hiding place; that indirect information the Nazis secured from another victim by torture.

Nazi forces—according to German sources, some 800 strong—converged on the church early on the morning of 18 June. An assault on the nave was repulsed by parachutists in the gallery, and the Germans secured the interior of the building only after heavy losses in three hours of fighting. The three parachutists took poison. Only by chance—the discovery of an article of clothing indicating that there were more than three men hiding in the building—led the Germans to the crypt, where four other parachutists were still concealed.

After the Czechs repulsed with gunfire all attempts to enter, the Germans sought to drive them out (for the order was to take them alive) by pumping tear gas into the crypt through a streetside ventilation slit. Using a ladder, the parachutists pushed away the gas hoses.

After the attackers managed to pull away the ladder, they began pumping in water with fire hoses.

The parachutists repulsed another assault by German troops who entered the crypt.

Contrary to some depictions, the parachutists' lives were not endangered by the water (which reached a height of only a few feet). But, trapped, having failed in their desperate attempt to find a rumored escape tunnel to the river, and low on ammunition, they took their own lives with their revolvers. Again contrary to some depictions, Kubiš and Gabčík did not die together in the crypt. Kubiš poisoned himself after the battle above ground.

I still remember very clearly the day my father took me to the site, still under the communist regime. I was impressed that he knew the event and topography so well and could immediately identify the street (Resslova) even though he was not present at the time and had not been there in years (indeed, decades). There wasn't much to see. This was of course well before the street became the fashionable place that it is now, anchored today by Frank Gehry's iconic "Fred and Ginger" edifice (1, 2) farther down, on the river. In fact, that was (if I may put it this way) one of the "discreet charms" of communist-era Central Europe. One had the feeling both that things had not changed, and that one was in the midst of history unfolding, because everything—from the drab, dirty gray or beige façades to the distinctive smell of coal smoke in the air—was so different from what one was used to in the west. At any rate, I distinctly recall my emotions upon seeing the pockmarks from gunfire around the ventilation slit, with its simple, understated memorial plaque—especially by virtue of the contrast when we later walked a few blocks farther and saw parents and children happily playing in the park on the island of Slovanský Ostrov.

When I returned to the site last year, it had acquired a much higher profile. The whole complex is now known as Národní památník hrdinů Heydrichiády - místo smíření (the National Memorial to the Heroes of the Heydrichiade—Site of Reconciliation). When one enters the church, one encounters a modest exhibit of placards (added in the 1990s), detailing the planning of the assassination, the event itself, and the aftermath. One can visit the interior of the church itself.

The focus, though, is the crypt, which has become a shrine. I had the good fortune (if one may put it that way) to be alone in the crypt for quite some time.

Here, too, one finds displays on the events—photographs and explanations, a bloodstained book belonging to one of the parachutists, a facsimile of the antitank grenade used in the attack, and so forth. Whether the average visitor spends a lot of time reading the "signage," I don't know. I certainly did, but that was not why I was there.

I knew the history, so what I came for was the sense of place. There is something peculiarly moving about having heard and read about a great human drama and then setting foot on the ground where it actually occurred: to see the catacombs, which first housed monks' bones, and then living parachutists, and, as the water level rose, their ammunition; the slit through which parachutists and Gestapo exchanged fire, through which the poison gas drifted and the water flowed; the hole that marked the beginning and end of the desperate search for the secret tunnel that could lead to salvation. It was scarcely less moving to see the many simple tributes from around the world, whether from former allied soldiers or just lovers of freedom and admirers of heroism.

As other visitors joined me in the cool crypt on that warm afternoon, I happened to notice two women speaking English. After some hesitation, I couldn't contain my curiosity and asked them what had brought them to this dark place on such a fine day. They responded that they had never heard of the episode until coming across a brief reference in a tourist map or guidebook, and had been so touched that they wanted to see it for themselves. I filled them in on more of the story. When I mentioned that I was next planning to head to the Army Museum in order to pursue the story, we agreed to go together. The car in which Heydrich was assassinated was no longer on display, but we were able to see the other displays on the war years, and above all, the end of a 2008 special exhibit on the anniversary of the "Mobilization" for war in 1938. After that, we parted ways: they for dinner with friends, I, for the Heydrich assassination monument.

I was, truth be told, deeply moved to find that the story of the parachutists and the ordeal of the Czech nation during the "Heydrichiade" had so touched people who had not natural personal or intellectual connection to those events of a lifetime ago. I had the sense that I had accomplished something, in several ways, that afternoon.

Postscript: This spring, Radio Prague reports, the site has undergone a complete overhaul. Separation of interpretive and memorial functions is intended to strengthen each:

The three men and their comrades from the other parachute teams at first went underground in safe houses, but as conditions became too dangerous, they found refuge in the crypt of the Orthodox Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius (named after the apostles to the Slavs). (The Germans persisted in calling it by the older name of Karel Borromeus Church, after the saint Carlo Borromeo, of the Counter-Reformation era, when Bohemia was forcibly recatholicized.) As the terror mounted, the parachutists were tormented by feelings of guilt and considered confessing and then committing suicide. Ultimately, they were persuaded to continue resistance, not least because there was no evidence that surrender would stop the reprisals.

By mid-June, just as there was hope (some realistic, most of it fanciful) that the parachutists would be able to flee the country, they were betrayed by one of their own, Karel Čurda, who, depending on which sources one believes, was moved by a combination of fear, anguish over the reprisals (including threats to his own family), and greed: the Nazis were offering a reward of 10 million Czech Crowns (1 million German Reichsmark) for information leading to the assassins. He identified the assassins but did not know their hiding place; that indirect information the Nazis secured from another victim by torture.

Nazi forces—according to German sources, some 800 strong—converged on the church early on the morning of 18 June. An assault on the nave was repulsed by parachutists in the gallery, and the Germans secured the interior of the building only after heavy losses in three hours of fighting. The three parachutists took poison. Only by chance—the discovery of an article of clothing indicating that there were more than three men hiding in the building—led the Germans to the crypt, where four other parachutists were still concealed.

After the Czechs repulsed with gunfire all attempts to enter, the Germans sought to drive them out (for the order was to take them alive) by pumping tear gas into the crypt through a streetside ventilation slit. Using a ladder, the parachutists pushed away the gas hoses.

After the attackers managed to pull away the ladder, they began pumping in water with fire hoses.

The parachutists repulsed another assault by German troops who entered the crypt.

Contrary to some depictions, the parachutists' lives were not endangered by the water (which reached a height of only a few feet). But, trapped, having failed in their desperate attempt to find a rumored escape tunnel to the river, and low on ammunition, they took their own lives with their revolvers. Again contrary to some depictions, Kubiš and Gabčík did not die together in the crypt. Kubiš poisoned himself after the battle above ground.

I still remember very clearly the day my father took me to the site, still under the communist regime. I was impressed that he knew the event and topography so well and could immediately identify the street (Resslova) even though he was not present at the time and had not been there in years (indeed, decades). There wasn't much to see. This was of course well before the street became the fashionable place that it is now, anchored today by Frank Gehry's iconic "Fred and Ginger" edifice (1, 2) farther down, on the river. In fact, that was (if I may put it this way) one of the "discreet charms" of communist-era Central Europe. One had the feeling both that things had not changed, and that one was in the midst of history unfolding, because everything—from the drab, dirty gray or beige façades to the distinctive smell of coal smoke in the air—was so different from what one was used to in the west. At any rate, I distinctly recall my emotions upon seeing the pockmarks from gunfire around the ventilation slit, with its simple, understated memorial plaque—especially by virtue of the contrast when we later walked a few blocks farther and saw parents and children happily playing in the park on the island of Slovanský Ostrov.

When I returned to the site last year, it had acquired a much higher profile. The whole complex is now known as Národní památník hrdinů Heydrichiády - místo smíření (the National Memorial to the Heroes of the Heydrichiade—Site of Reconciliation). When one enters the church, one encounters a modest exhibit of placards (added in the 1990s), detailing the planning of the assassination, the event itself, and the aftermath. One can visit the interior of the church itself.

The focus, though, is the crypt, which has become a shrine. I had the good fortune (if one may put it that way) to be alone in the crypt for quite some time.

Here, too, one finds displays on the events—photographs and explanations, a bloodstained book belonging to one of the parachutists, a facsimile of the antitank grenade used in the attack, and so forth. Whether the average visitor spends a lot of time reading the "signage," I don't know. I certainly did, but that was not why I was there.

I knew the history, so what I came for was the sense of place. There is something peculiarly moving about having heard and read about a great human drama and then setting foot on the ground where it actually occurred: to see the catacombs, which first housed monks' bones, and then living parachutists, and, as the water level rose, their ammunition; the slit through which parachutists and Gestapo exchanged fire, through which the poison gas drifted and the water flowed; the hole that marked the beginning and end of the desperate search for the secret tunnel that could lead to salvation. It was scarcely less moving to see the many simple tributes from around the world, whether from former allied soldiers or just lovers of freedom and admirers of heroism.

As other visitors joined me in the cool crypt on that warm afternoon, I happened to notice two women speaking English. After some hesitation, I couldn't contain my curiosity and asked them what had brought them to this dark place on such a fine day. They responded that they had never heard of the episode until coming across a brief reference in a tourist map or guidebook, and had been so touched that they wanted to see it for themselves. I filled them in on more of the story. When I mentioned that I was next planning to head to the Army Museum in order to pursue the story, we agreed to go together. The car in which Heydrich was assassinated was no longer on display, but we were able to see the other displays on the war years, and above all, the end of a 2008 special exhibit on the anniversary of the "Mobilization" for war in 1938. After that, we parted ways: they for dinner with friends, I, for the Heydrich assassination monument.

I was, truth be told, deeply moved to find that the story of the parachutists and the ordeal of the Czech nation during the "Heydrichiade" had so touched people who had not natural personal or intellectual connection to those events of a lifetime ago. I had the sense that I had accomplished something, in several ways, that afternoon.

* * *

Postscript: This spring, Radio Prague reports, the site has undergone a complete overhaul. Separation of interpretive and memorial functions is intended to strengthen each:

Colonel Aleš Knížek of the Czech Military Institute was behind the facelift.

“Museum items were removed from the actual crypt itself and placed here in this anteroom. Our aim was to make the crypt more solemn – it will now contain only seven busts of the parachutists who died here in this church. The anteroom maps the Czechoslovak resistance movement, and contains items that they used here in the crypt, as well as in the assassination of Heydrich.”

Thursday, June 17, 2010

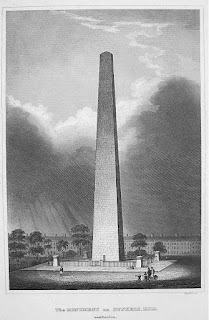

17 June 1775: Bunker Hill; winners and losers

What a nice feeling it is when everything comes together serendipitously. And the essay or the web and the world of the hyperlink is often the perfect venue for the kind of lateral thinking that perhaps originated with Montaigne.(What couldn't he have done with a blog?)

I recently spoke of modern war being fought more than ever as a battle of perceptions, though I noted that the phenomenon is of course much older. As chance would have it, this week brought two perfect illustrations, one old, and one new—and fate moreover conspired to conjoin them.

Most of us here were thrilled when Team USA pulled off a tie against the vaunted English in early World Cup action. We had been told we'd never get this far. Naturally, the New York Post could not contain its pride:

The headline caused quite a stir, and some of our English friends took umbrage at it.

Actually, I thought the notorious Post (not unlike the Sun, though a cut or two above that) got things more or less right here: They just had to be triumphalist somehow, knew it was no outright victory but could nonetheless count as one, and picked the proper historical reference. They knew that the famous Battle of Bunker Hill was not a military success. I rather doubt that many students or even the average adult would know that.

Far from operating out of jingoism and iignorance (as some outraged commentators charged), the writers at the Post moreover displayed (I think) a nice sense of self-deprecating humor; they could use a bit more of that.

The timing was actually fortuitously good, if not perfect, for the match came less than a week before the anniversary of the Battle.

For those of you in need of a little refresher, here's last year's post.

Everything's relative, right? I mean, if Dunkirk can count as a major success (only because it wasn't a total disaster), then why not Bunker Hill and a 1-1 World Cup Tie?

I recently spoke of modern war being fought more than ever as a battle of perceptions, though I noted that the phenomenon is of course much older. As chance would have it, this week brought two perfect illustrations, one old, and one new—and fate moreover conspired to conjoin them.

Most of us here were thrilled when Team USA pulled off a tie against the vaunted English in early World Cup action. We had been told we'd never get this far. Naturally, the New York Post could not contain its pride:

The headline caused quite a stir, and some of our English friends took umbrage at it.

Actually, I thought the notorious Post (not unlike the Sun, though a cut or two above that) got things more or less right here: They just had to be triumphalist somehow, knew it was no outright victory but could nonetheless count as one, and picked the proper historical reference. They knew that the famous Battle of Bunker Hill was not a military success. I rather doubt that many students or even the average adult would know that.

Far from operating out of jingoism and iignorance (as some outraged commentators charged), the writers at the Post moreover displayed (I think) a nice sense of self-deprecating humor; they could use a bit more of that.

The timing was actually fortuitously good, if not perfect, for the match came less than a week before the anniversary of the Battle.

For those of you in need of a little refresher, here's last year's post.

Everything's relative, right? I mean, if Dunkirk can count as a major success (only because it wasn't a total disaster), then why not Bunker Hill and a 1-1 World Cup Tie?

17 June: a very busy day in history

Sometimes it seems that certain dates are just chock-full of historical anniversaries, at least as tabulated by the standard sites, such as those listed in the links on the right-hand column of this blog.

On the one hand, these lists are necessarily incomplete and can appear subjective. On the other hand, they're still comprehensive enough to overwhelm the average reader, leaving a sense of chaos; today's Wikipedia date page has some 40-odd entries. Many of us will be familiar with some of the events, even if we don't know the dates off the tops of our heads. For example: We've all heard of the Taj Mahal, but this was the date in 1631 (by the Christian calendar) on which Mumtaz Mahal died in childbirth, after which Mughal emperor Shah Jahan I would spend over two decades building her famous mausoleum. Recent years have seen the revival of the debate on the values of protectionism vs. free trade. Today is the anniversary of the date on which, in 1930, Herbert Hoover signed into law the notorious Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, widely seen as a provincial and stupid measure that exacerbated the effects of the Depression. Most of us, either before or after learning about the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (maybe both), took the SAT college entrance examination. It was on this date in 1901 that the College Board introduced its first standardized test. And we all (of a certain age) remember watching that infamous "televised low-speed highway chase," in the course of which police followed ("don't squeeze The Juice!") former football star O. J. Simpson and then arrested him for the murder of his wife and her friend—though we've likely forgotten that it occurred on this day in 1994.

But how many of us know of these events associated with June 17: Iceland's declaration of independence from Denmark (1944); "Sir Francis Drake claims a land he calls Nova Albion (modern California) for England" (1579); "The Wooden Roller Coaster at Playland, which is in the Pacific National Exhibition, Vancouver, Canada opens" (1958; and we should care because . . .??); President Nixon declares war on drugs (1971; yeah, that one really worked); Matsunaga Hisahide assassinates the 13th Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru (1565, by the Christian calendar). "With the death of the last individual, the Dusky Seaside Sparrow becomes extinct." (1987; the definitive extinction of a unique life-form would seem to be far more important than the birth of a roller coaster)? And even diehard vampirologists may be forgiven for forgetting that it was on this date in 1462 that "Vlad III the Impaler attempts to assassinate Mehmed II (The Night Attack) forcing him to retreat from Wallachia."

Still, the 17th of June is an important date by any standard. Let me try, quickly, casually, and informally, to connect a few of the events within my field of modern history.

As a midwestern schoolchild, I had to learn a lot about regional history, so I was of course aware of the exploration of the upper Great Lakes region by French "voyageurs" and priests (some of our cities, counties, colleges, and streets, etc. are still named for them). It was on this date in 1673 that Father Jacques Marquette and French-Canadian explorer Louis Jolliet became the first Europeans to reach the Mississippi, at present-day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. In the meantime, the English colonies were growing. After emerging victorious from a struggle with the French in the middle of the next century, they began to assert themselves against their own mother country, and it was on this date in 1775 that the famous Battle of Bunker Hill took place: a practical victory for the British, who took the heights, but a moral and psychological victory for the American revolutionaries, who held their ground longer than expected. To the surprise of everyone in Europe, democratic and radical sentiments welled up in France in 1789, and on this date, the Third Estate—given only one third of the vote in the corporatist arrangements of the Estates-General, though representing well over 90 percent of the population—asserted that it was in fact "the nation" and declared itself the "National Assembly." It was in many ways a far more revolutionary act than the storming of the Bastille (still a month in the offing), though the latter, for better or worse, became the iconic representation of revolutionary change for nearly two centuries. The bond between the United States and France, forged during the Revolutionary era in the days of the Marquis de Lafayette, generally remained strong, the more so in the years after 1871, when republican forces in France at last vanquished the serious threat from monarchist and Bonapartist factions. It was on this date in 1885 that the Statue of Liberty, the iconic representation of the revolutionary promise, given by the French to the Americans, arrived in New York as a belated Centennial gift. The spirit of popular rebellion did not die out in America, for on this date in 1932 the "Bonus Army" of disgruntled World War I veterans—men who had gone to fight for the liberation of France with the motto, "Lafayette, we are here"—marched on and camped in Washington, demanding benefits. The French Revolution had introduced the guillotine as a humane means of execution, but it was only on this date in 1939 that the last public guillotining in France took place (the instrument remained in use until 1977, though behind prison doors). Exactly a year later, Allied (mainly British) troops were beginning a desperate but disciplined seaborne retreat from France, pressed by invading German forces. "The only major loss during the evacuation from western France" was the sinking of the RMS Lancastria, on this date, with a cost of 5,800 lives. On that same day, the Soviet Union, which in 1939 had entered into a cynical pact with Nazi Germany and shared in the division of Poland, occupied and annexed the Baltic states. After the war's close, Soviet rule expanded to the rest of East-Central Europe but faced periodic moments of resistance, large and small. The first of these major episodes was the protest by East German workers in 1953, which began as an action against increased work norms, but mushroomed into a miniature rebellion that had to be put down with force by East German police and Soviet troops. As Bertolt Brecht, who managed to be both a celebrated and transgressive poet of the regime, famously and sarcastically said,

One could of course read this—crudely and ideologically—as a triumphalist paean to liberal democracy. A fine thing though the latter system is, that is not my purpose, for that would, among other things, be unhistorical. Just as the socialism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries failed to live up to its expectations or was betrayed, so, too, liberalism faced its challenges and generated contradictions and failures. The American and French Revolutions did not in fact go so far as to provide rights for all. Nonetheless, they established principles that generated a self-critical process eventually capable of correcting itself and expanding the range of beneficiaries. The socialist impulse lives on within the labor and social democratic movements in the context of the industrial democracies and Socialist International. Whether it is capable of reasserting itself there or as an independent alternative remains to be seen. Be that as it may, it has already transformed liberal democracy itself, and that may be its ultimate achievement: like the creation of the National Assembly, less visible or memorable than some other, more dramatic developments, but perhaps with deeper consequences.

And, lest we forget, the balance of history can tip swiftly and frequently: in the 1930s and 1940s, many of the shrewdest observers wrote off liberal democracy as dead; the new dictatorships appeared as the wave of the future. At the end of the Cold War, as many of us remember all too well, we were told that we had reached (in Francis Fukuyama's phrase), "the end of history," after which liberal capitalist democracy would be the only game in town. Didn't quite work out that way.

Stay tuned.

On the one hand, these lists are necessarily incomplete and can appear subjective. On the other hand, they're still comprehensive enough to overwhelm the average reader, leaving a sense of chaos; today's Wikipedia date page has some 40-odd entries. Many of us will be familiar with some of the events, even if we don't know the dates off the tops of our heads. For example: We've all heard of the Taj Mahal, but this was the date in 1631 (by the Christian calendar) on which Mumtaz Mahal died in childbirth, after which Mughal emperor Shah Jahan I would spend over two decades building her famous mausoleum. Recent years have seen the revival of the debate on the values of protectionism vs. free trade. Today is the anniversary of the date on which, in 1930, Herbert Hoover signed into law the notorious Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, widely seen as a provincial and stupid measure that exacerbated the effects of the Depression. Most of us, either before or after learning about the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (maybe both), took the SAT college entrance examination. It was on this date in 1901 that the College Board introduced its first standardized test. And we all (of a certain age) remember watching that infamous "televised low-speed highway chase," in the course of which police followed ("don't squeeze The Juice!") former football star O. J. Simpson and then arrested him for the murder of his wife and her friend—though we've likely forgotten that it occurred on this day in 1994.

But how many of us know of these events associated with June 17: Iceland's declaration of independence from Denmark (1944); "Sir Francis Drake claims a land he calls Nova Albion (modern California) for England" (1579); "The Wooden Roller Coaster at Playland, which is in the Pacific National Exhibition, Vancouver, Canada opens" (1958; and we should care because . . .??); President Nixon declares war on drugs (1971; yeah, that one really worked); Matsunaga Hisahide assassinates the 13th Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru (1565, by the Christian calendar). "With the death of the last individual, the Dusky Seaside Sparrow becomes extinct." (1987; the definitive extinction of a unique life-form would seem to be far more important than the birth of a roller coaster)? And even diehard vampirologists may be forgiven for forgetting that it was on this date in 1462 that "Vlad III the Impaler attempts to assassinate Mehmed II (The Night Attack) forcing him to retreat from Wallachia."

Still, the 17th of June is an important date by any standard. Let me try, quickly, casually, and informally, to connect a few of the events within my field of modern history.

As a midwestern schoolchild, I had to learn a lot about regional history, so I was of course aware of the exploration of the upper Great Lakes region by French "voyageurs" and priests (some of our cities, counties, colleges, and streets, etc. are still named for them). It was on this date in 1673 that Father Jacques Marquette and French-Canadian explorer Louis Jolliet became the first Europeans to reach the Mississippi, at present-day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. In the meantime, the English colonies were growing. After emerging victorious from a struggle with the French in the middle of the next century, they began to assert themselves against their own mother country, and it was on this date in 1775 that the famous Battle of Bunker Hill took place: a practical victory for the British, who took the heights, but a moral and psychological victory for the American revolutionaries, who held their ground longer than expected. To the surprise of everyone in Europe, democratic and radical sentiments welled up in France in 1789, and on this date, the Third Estate—given only one third of the vote in the corporatist arrangements of the Estates-General, though representing well over 90 percent of the population—asserted that it was in fact "the nation" and declared itself the "National Assembly." It was in many ways a far more revolutionary act than the storming of the Bastille (still a month in the offing), though the latter, for better or worse, became the iconic representation of revolutionary change for nearly two centuries. The bond between the United States and France, forged during the Revolutionary era in the days of the Marquis de Lafayette, generally remained strong, the more so in the years after 1871, when republican forces in France at last vanquished the serious threat from monarchist and Bonapartist factions. It was on this date in 1885 that the Statue of Liberty, the iconic representation of the revolutionary promise, given by the French to the Americans, arrived in New York as a belated Centennial gift. The spirit of popular rebellion did not die out in America, for on this date in 1932 the "Bonus Army" of disgruntled World War I veterans—men who had gone to fight for the liberation of France with the motto, "Lafayette, we are here"—marched on and camped in Washington, demanding benefits. The French Revolution had introduced the guillotine as a humane means of execution, but it was only on this date in 1939 that the last public guillotining in France took place (the instrument remained in use until 1977, though behind prison doors). Exactly a year later, Allied (mainly British) troops were beginning a desperate but disciplined seaborne retreat from France, pressed by invading German forces. "The only major loss during the evacuation from western France" was the sinking of the RMS Lancastria, on this date, with a cost of 5,800 lives. On that same day, the Soviet Union, which in 1939 had entered into a cynical pact with Nazi Germany and shared in the division of Poland, occupied and annexed the Baltic states. After the war's close, Soviet rule expanded to the rest of East-Central Europe but faced periodic moments of resistance, large and small. The first of these major episodes was the protest by East German workers in 1953, which began as an action against increased work norms, but mushroomed into a miniature rebellion that had to be put down with force by East German police and Soviet troops. As Bertolt Brecht, who managed to be both a celebrated and transgressive poet of the regime, famously and sarcastically said,

As a workers' protest that assumed the form of a challenge to the regime, as such, the 1953 revolt anticipated the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the Prague Spring of 1968, and the the Polish Solidarity movement of 1980. Dissent welled up on both sides of the Iron Curtain. In the United States, protesters against racial discrimination and the Vietnam War built on the example of the Bonus Army and marched on Washington. At the height of the debate over the war and in the midst of an election campaign, agents of President Nixon were arrested on this date in 1972 in a bungled break-in at Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington. Two years later, he was driven from office under threat of impeachment. In the eyes of most observers, the democratic constitutional system established by the Revolution had withstood its most severe threat.After the uprising of the 17th of June

The Secretary of the Writers Union

Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee

Stating that the people

Had forfeited the confidence of the government

And could win it back only

By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

One could of course read this—crudely and ideologically—as a triumphalist paean to liberal democracy. A fine thing though the latter system is, that is not my purpose, for that would, among other things, be unhistorical. Just as the socialism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries failed to live up to its expectations or was betrayed, so, too, liberalism faced its challenges and generated contradictions and failures. The American and French Revolutions did not in fact go so far as to provide rights for all. Nonetheless, they established principles that generated a self-critical process eventually capable of correcting itself and expanding the range of beneficiaries. The socialist impulse lives on within the labor and social democratic movements in the context of the industrial democracies and Socialist International. Whether it is capable of reasserting itself there or as an independent alternative remains to be seen. Be that as it may, it has already transformed liberal democracy itself, and that may be its ultimate achievement: like the creation of the National Assembly, less visible or memorable than some other, more dramatic developments, but perhaps with deeper consequences.

And, lest we forget, the balance of history can tip swiftly and frequently: in the 1930s and 1940s, many of the shrewdest observers wrote off liberal democracy as dead; the new dictatorships appeared as the wave of the future. At the end of the Cold War, as many of us remember all too well, we were told that we had reached (in Francis Fukuyama's phrase), "the end of history," after which liberal capitalist democracy would be the only game in town. Didn't quite work out that way.

Stay tuned.

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

Stop random neighborhood violence: regulate pugilism through historic preservation!

Do good historic preservation bylaws good neighbors make? (with apologies to Robert Frost) Several residents have already called this passage in a current newspaper article to my attention, and it immediately caught my eye, too, so I can hardly allow it to pass without comment:

Still, far more embarrassing typos are possible, even in historic preservation stories. I came across this naughty little howler recently while reviewing coverage of the controversies surrounding Edith Wharton's The Mount. But I digress.

Actually, the typo is inadvertently appropriate in its way:

Local historic districts exist in order to enforce the public interest in protecting historic resources. However, they also serve to maintain historic neighbor character in the broadest sense. Even if a given homeowner dutifully preserves his or her property in the appropriate manner, there is, absent such regulation, no guarantee that a neighbor or new property owner will do likewise. So, in that sense, a local district ordinance, developed on the basis of residents' preferences and duly approved by local government, could actually help to resolve conflict and preserve neighborhood peace. Nonetheless, a local district commission can regulate only proposed changes to architectural features of buildings visible from the public way. Residents will still have to organize fights on their own.

"If established, a locally appointed Historic District Commission would review any proposed changes to the exterior of buildings as viewed from public ways and would have to issue certificates of approval for property owners proposing any altercations."Whoops: little typo there, Scott (or whoever did the data entry).

Still, far more embarrassing typos are possible, even in historic preservation stories. I came across this naughty little howler recently while reviewing coverage of the controversies surrounding Edith Wharton's The Mount. But I digress.

Actually, the typo is inadvertently appropriate in its way:

Local historic districts exist in order to enforce the public interest in protecting historic resources. However, they also serve to maintain historic neighbor character in the broadest sense. Even if a given homeowner dutifully preserves his or her property in the appropriate manner, there is, absent such regulation, no guarantee that a neighbor or new property owner will do likewise. So, in that sense, a local district ordinance, developed on the basis of residents' preferences and duly approved by local government, could actually help to resolve conflict and preserve neighborhood peace. Nonetheless, a local district commission can regulate only proposed changes to architectural features of buildings visible from the public way. Residents will still have to organize fights on their own.

Daily Hampshire Gazette, 15 JuneHaving announced the process here at the outset, I'll continue to provide updates as it unfolds.

"Forum tonight targets Dickinson area"

[also published yesterday as "Forum to be held Tuesday in Amherst in historic district surrounding Dickinson homestead"]

By Scott Merzbach

AMHERST - A public information forum about a proposed Local Historic District surrounding the Emily Dickinson Museum and Homestead will be held tonight from 7 to 8:30 p.m. at the Amherst Woman's Club at 35 Triangle St.

The Local Historic District Study Committee is encouraging residents, especially property owners, to attend the session.

The forum will include presenting material outlining the historical significance of the Dickinson National Register Historical District and the Main Street neighborhood, the process to establish a local district and the sets of rules and regulations accompanying such a district.

Jerry Guidera, a member of the committee, said in an email that this would be the first local historic district in Amherst

"If the Dickinson neighborhood local historic district is adopted by Town Meeting next spring, there would likely be efforts to establish local historic districts in other areas of town," Guidera said.

The Select Board created the study committee in fall 2008 after the Historical Commission brought it forward. If established, a locally appointed Historic District Commission would review any proposed changes to the exterior of buildings as viewed from public ways and would have to issue certificates of approval for property owners proposing any altercations.

Amherst has nine historic districts and buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, but these don't offer the same level of protection to structures that a local historic district would.

A handout at the forum will ask property owners to provide feedback on the historical character of the neighborhood.

For more information, call Nathaniel Malloy in the town's Planning Department at 259-3040.

First Phase in Restoration of Amherst's Civil War Tablets Complete

Scott Merzbach recently published this report on the work of the Historical Commission. I'll follow up shortly with a posting of my own.

[Postscript: I see that, as sometimes happens, I did not manage to do a follow-up at that time. Stay tuned.]

from the Daily Hampshire Gazette:

Civil War plaques restored in Amherst but remain mothballed

By smerzbach

Created 06/04/2010 - 04:00

AMHERST - Restoration is complete of six memorial plaques recognizing more than 300 residents who fought in the Civil War, but how and when these tablets get put back on display remains uncertain.

For close to a decade, town officials and residents have planned to get the large marble plaques, which include the names of black soldiers who were part of the famous 54th Regiment, installed in a public place so residents can once again view them.

Historical Commission Chairman Jim Wald said Wednesday that this process can now start with hiring consultants who know how best to display the memorials.

"With the conservation process complete, we're trying to find a place to store them and to take the next step to get engineering studies under way," Wald said.

Town Manager Larry Shaffer, though, said getting to the point where they can be shown will not be easy, but it is essential that this happens.

"It's an important project from a historical perspective," Shaffer said. "If we're going to celebrate history, we want them out so the public can view them."

All the plaques were commissioned in 1893 by the local Grand Army of the Republic post, a veterans organization for the Civil War. After being in various parts of Town Hall for close to a century, including the basement when it was the town's police station, the plaques were moved during mid-1990's renovations and have been stored at the Ruxton gravel pit in North Amherst since.